Etiology of the symptom

Sensitive skin reacts to sudden changes in ambient temperature, which is manifested by a feeling of heat.

A common reason why the face, in particular the forehead, can burn is a change in ambient air temperature. The provoking factor in this case is a sensitive skin type, which reacts in this way, for example, when leaving a hot bath into a cooler room.

When you get a sunburn or, conversely, frostbite, the skin loses moisture. This provokes thinning of the epidermis and an increase in its sensitivity to harmful external factors.

If there is no fever, but the forehead and cheeks are hot, this may be a consequence of drinking alcohol. In addition to facial redness, blood pressure may rise and swelling may occur.

If spicy spices were added during the preparation of the dish, your forehead or cheeks may turn red after the feast. This is the body’s reaction to the seasoning, which can be complemented by increased heart rate and disruption of the gastrointestinal tract.

A natural phenomenon is facial redness after high physical exertion. It is not recommended to abuse them. If the load is significantly exceeded, a heart attack is possible.

Diseases that occur with redness of the face

Various dermatological diseases occur with redness of the skin of the face, in particular the forehead, cheeks, and nose. This could be acne or rosacea, demodicosis, psoriasis, etc. Hot to the touch and reddened areas are caused by vasodilation. The disease progresses with the formation of a specific rash, which has a distinctive appearance in each specific case.

If a person suffers from hypersensitivity of the skin to a certain provoking factor, for example, to a specific type of cosmetics or material for making hats, in addition to an increase in local temperature and redness of the face, the action of the provocateur causes itching, burning, and swelling, which can reach an impressive size.

Acute respiratory infections and colds may not be accompanied by an increase in general temperature, but occur with heat in the face and redness. Symptoms include general malaise, runny nose, cough, and drowsiness.

As the disease progresses, fever, chills, sneezing, and increased lacrimation occur. To prevent complications, you need to stay in bed and follow the recommendations indicated by your doctor.

Redness of the forehead and face in general is often observed in people suffering from osteochondrosis of the cervical spine. In addition, I have a throbbing headache. Symptoms are caused by insufficient oxygen supply to the brain due to impaired circulation in the cervical structures.

Vegetative-vascular dystonia is another pathology that is not officially recognized as a disease, but causes quite pronounced symptoms that interfere with the quality of life. In addition to facial redness and hot flashes, a person is worried about a rapid heartbeat, a feeling of shortness of breath, a panic attack, and increased sweating. The body may become covered with red spots, which is caused by vascular spasm.

Diseases of the thyroid gland and changes at the hormonal level (during pregnancy, menopause, adolescence) often occur with hot flashes and a feeling of heat on the face.

A hot forehead is a symptom of diseases of the cardiovascular system. This could be hypertension, which occurs with headaches, a feeling of lack of air, and swelling.

Most psychological disorders occur with a rush of blood to the head and redness of the face. Neuroses and psycho-emotional fatigue are accompanied by similar symptoms.

Causes of nausea, chills, headache

Headache, nausea, chills, weakness and other symptoms can also appear in a healthy person, in the absence of any disorders. They arise as a result of fatigue, stress, intense physical activity. However, they can also indicate dangerous diseases and conditions that require immediate medical attention.

Intoxication

The most common cause is food poisoning. Stale foods, unripe fruits and berries, and low-quality alcohol lead to the accumulation of toxins in the blood. They are carried throughout the body, deposited in organs and tissues, and in difficult cases they can enter the brain. Headache, nausea, vomiting, chills are a typical reaction to poisoning, an attempt by the body to remove toxins and toxic substances.

There are several types of poisoning that can occur at home or in connection with the patient’s professional activities:

- foodborne - happens to any person, but can also pose a great danger to health;

- alcohol poisoning is a separate type that can cause disruption of the central nervous system due to the accumulation of toxic products of ethyl alcohol metabolism;

- medicinal – develops with an overdose of certain groups of drugs;

- poisoning with toxic gases, including carbon monoxide, requires immediate hospitalization of the victim.

Treatment for poisoning is aimed at removing poisons from the body and restoring the normal functioning of the affected organs and systems. For this purpose, sorbents are prescribed - drugs that absorb toxins in case of food poisoning. Droppers with electrolyte solutions are also effective for reducing the concentration of toxic compounds in the blood.

Increased blood pressure

Chronic hypertension is a dangerous disease that is manifested by increased blood pressure. The diagnosis is made if systolic pressure remains at 140 mm. rt. Art., and diastolic – 90 mm. rt. Art. Constant filling of blood vessels makes their walls dense and insufficiently elastic, which causes increased stress on the heart. The walls of the heart in the initial stages of the disease are hypertrophied, dense, and then gradually become thinner. The danger for the patient is that with elevated blood pressure, the risks of myocardial infarction, stroke and other diseases increase significantly.

Chronic hypertension manifests itself in attacks. Physical activity, infectious diseases, and changes in weather conditions lead to a sharp jump in blood pressure. This condition is manifested by the following symptoms:

- acute headache, dizziness;

- weakness, shortness of breath, pain in the heart;

- nausea and vomiting;

- redness of the skin, possible appearance of small pinpoint hemorrhages due to rupture of capillaries.

The patient is advised to strictly dose exercise and follow a low-salt diet. At home, it is necessary to monitor blood pressure readings and, if necessary, take medications to lower it in a course. It is important to understand that a sharp increase in pressure can trigger the rupture of important vessels that carry blood to the brain, and the development of a hemorrhagic stroke.

Reduced pressure

Arterial hypotension is a chronic decrease in blood pressure to 90/60 mm. rt. Art. and less. The condition can be caused by a malfunction of the cardiovascular system, and may also manifest itself as a secondary disease. Its cause may be thyroid disease, heart failure, inflammatory diseases of the lining of the heart. In addition, hypotension develops with systemic intake of diuretics (diuretics), antiarrhythmic and antihypertensive drugs, and psychotropic drugs.

An attack of low blood pressure is accompanied by characteristic symptoms. These include:

- pressing headache, weakness and dizziness;

- chills, lethargy, drowsiness, decreased performance;

- pallor of the skin and mucous membranes;

- nausea, vomiting.

Patients with chronic hypotension are often dependent on weather conditions. Attacks occur during the off-season or in hot weather, when atmospheric pressure decreases. Persistent hypotension can cause chronic ischemia (lack of oxygen) of certain areas, including those located in the brain. However, if low blood pressure does not cause deterioration in health, the patient should not worry. This condition is the prevention of diseases associated with chronic hypertension, including atherosclerosis, heart attack and stroke.

Infectious diseases

Respiratory viral diseases are a common cause of headache, chills, and fever. Flu, ARVI, and tonsillitis in the initial stages cause weakness and a sharp deterioration in well-being. It is important to remember that they are transmitted by airborne droplets and at the first sign, stay in bed and limit contact with other people. As the disease develops, the patient exhibits the following symptoms:

- sore throat, redness of the mucous membrane;

- sneezing, coughing, wheezing during breathing;

- high fever accompanied by chills;

- headache.

Infectious diseases that affect the gastrointestinal tract can also cause headaches, chills, fever, nausea and vomiting. Viruses and bacteria multiply on the intestinal mucosa, causing digestive problems. Infection with salmonellosis, intestinal flu and other diseases occurs through consumption of poorly peeled vegetables and fruits, contaminated water, meat and eggs without heat treatment. For treatment, antibiotics and symptomatic drugs are used that relieve intoxication and restore intestinal microflora. Treatment in a hospital setting is recommended to allow round-the-clock monitoring of the patient and prevent further spread of the infection.

Migraine

Migraines are attacks of headaches, the origin of which is not fully understood. They are associated with vascular pathologies, insufficient blood supply to certain areas of the brain. A characteristic symptom is a “migraine aura,” which appears several hours before the onset of a headache attack. At this time, the patient feels a deterioration in health and the following symptoms:

- nausea and vomiting;

- dizziness, loss of coordination of movements;

- chills, pale skin and mucous membranes;

- decreased hearing and visual acuity;

- increased sensitivity to light, lacrimation.

At home, you can use painkillers that will improve your well-being during migraines. However, in acute attacks they are ineffective. After examining and determining the headache, the doctor prescribes special anti-migraine medications - they should be taken according to prescription to relieve pain. You should also avoid situations that can trigger a migraine exacerbation. For different patients, these include intense physical activity, fatigue, lack of sleep and disruption of routine, and sudden changes in climatic conditions.

Digestive tract diseases

Diseases of the stomach and intestines are one of the reasons why nausea, vomiting, headache and fever appear. They are often of inflammatory origin and are associated with improper or irregular nutrition. However, digestive disorders may be associated with congenital disorders: insufficient secretion of gastric juice, autoimmune processes and other reasons.

- Gastritis is a common disease, inflammation of the gastric mucosa. It is characterized by pain in the upper abdomen, nausea, and heartburn. Symptoms appear most clearly after overeating or prolonged fasting, as well as after eating fatty foods. With hypoacid gastritis, the level of hydrochloric acid in gastric juice is reduced, and with hypoacid gastritis, it is increased.

- Peptic ulcer – during diagnosis, ulcers are found on the mucous membrane of the stomach and duodenum. The condition is accompanied by heartburn, nausea and vomiting, and heaviness in the abdomen. It is important for the patient to follow the prescribed diet and take medications, since ulcers can increase in size and cause perforation of the stomach or intestinal wall.

- Pancreatitis is inflammation of the pancreas. It secretes important enzymes into the duodenum that are necessary to break down food. The causes of pancreatitis may be poisoning, regular alcohol consumption, or mechanical damage to the pancreas. The disease is accompanied by indigestion, heaviness in the abdomen after eating a heavy meal, and pain in the left side.

- Hepatitis is an inflammation of the liver parenchyma. If the disease is of non-contagious origin, it is associated with prolonged intoxication and poor nutrition. Separately, there is alcoholic hepatitis, which occurs with regular intake of even a small amount of ethyl alcohol. Infection with viral hepatitis occurs when the pathogen enters the bloodstream of a healthy person. The disease does not manifest itself in any way at the initial stages, but in advanced cases it can lead to the development of cirrhosis of the liver.

- Crohn's disease is an autoimmune disorder. Disruption of the immune system leads to inflammation of the mucous membrane of the small intestine, constant nausea and abdominal pain. Treatment is symptomatic, and some patients may require surgery to remove the damaged part of the intestine.

Diseases of the stomach and intestines can be diagnosed at any age. To prevent them, it is important to follow a diet and choose quality products. Fried foods, sweets, and a large amount of animal fats in the diet cause increased stress on the liver, stomach, and pancreas. If gastritis, enteritis, pancreatitis, or hepatitis are suspected, doctors must prescribe a gentle diet. It includes boiled vegetables and cereals, lean meats and fish. It is recommended to take food in small portions, at least 5 times a day.

Other reasons

Nausea, chills, weakness, headache are nonspecific signs that make it difficult to make a diagnosis without additional examinations. They can indicate a variety of conditions and disorders, including:

- diabetes mellitus is a chronic metabolic disease that leads to increased blood glucose levels;

- neoplasms – tumors located in the brain are of great danger;

- vegetative-vascular dystonia;

- renal failure - can be caused by intoxication of the body, systemic use of certain medications;

- the consequences of traumatic brain injuries appear even many years after the injury.

In some patients, nausea and headaches develop under severe stress or nervous tension. Preparing for exams, insomnia, anxiety before an important event negatively affects the state of the nervous system. To improve well-being, herbal sedatives and proper rest are recommended.

Symptoms and manifestations

A hot head is not a separate disease, but a symptom that accompanies certain pathologies. Feelings in this condition:

- sudden rush of blood to the forehead or other part of the face;

- redness of the forehead;

- increased sweating.

Associated symptoms:

- fear and anxiety;

- headache and dizziness;

- lack of air;

- increased heart rate;

- increased sweating;

- nausea;

- hand tremors

Depending on the cause of the facial heat, the duration of the symptom may vary for each patient. The condition may improve within a minute or persist for one day or more.

Diagnostic methods

Headache, nausea and vomiting, chills and fever are signs of infectious and non-infectious diseases that require different treatment methods. To prescribe the optimal regimen, it is important to determine the cause of these symptoms. After the examination, the doctor prescribes additional examinations that will help make a final diagnosis:

- Ultrasound of the stomach and intestines is the first way to determine inflammatory processes;

- endoscopic examination of the mucous membrane of the stomach and intestines;

- magnetic resonance or computed tomography – methods for diagnosing the brain to detect tumors;

- measuring blood pressure during the day;

- Ultrasound of the heart, electrocardiography - prescribed for suspected heart failure and other diseases;

- blood tests - will help determine inflammatory diseases and dysfunction of individual organs;

- specific blood tests to determine glucose levels.

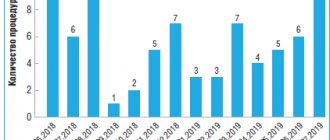

At the Clinical Brain Institute, the examination regimen is prescribed individually. It does not include any unnecessary, insufficiently informative tests that will not help assess the overall picture of the disease. Modern equipment allows you to obtain the most accurate data necessary for diagnosis.

Diagnosis and treatment

To exclude or confirm an allergic reaction, special tests are done.

To exclude the allergic nature of the heat on the face, skin tests and other studies are performed. To exclude a disease of dermatological etiology, a sample of biological material taken from the patient is taken by scraping. A blood test is required to exclude the infectious nature of the symptom.

Treatment is prescribed depending on the cause of the heat on the face.

- Normalization of the emotional background. If a person has suffered stress, you need to take a sedative that will help get rid of anxiety and anxiety.

- The right way of life. It is necessary to eliminate bad habits (smoking, drinking alcohol, taking drugs) that negatively affect the condition and functioning of blood vessels.

- Maintaining a balanced diet. Spices, hot seasonings, spices, fatty, fried, smoked foods should be excluded.

- Using cosmetics that suit your skin type. It is better to select cosmetic products marked “hypoallergenic” or with a composition that is closest to natural.

If you have a hot face and redness caused by hypothermia, overheating, or exposure to other external factors, you can try to cope on your own using folk remedies:

- oatmeal: 2 tbsp. pour 50 ml of boiling water over the flakes, leave to steam for 20 minutes, apply the paste to the forehead, leave for half an hour;

- cottage cheese and kefir: mix the ingredients in equal quantities, apply the mask to the face, leave for 20-30 minutes;

- cucumber: peel the vegetable, grate the pulp, apply to the face, leave for 10-20 minutes.

If you suspect a specific disease, which may occur with fever on the face, it is recommended to visit a doctor and undergo a comprehensive diagnosis.

Hot flashes in menopause: a compelling alternative to hormone replacement therapy

Hot flashes, according to patients and medical specialists, are the most characteristic and unpleasant menopausal symptom [1, 2]. Depending on the severity, hot flashes can have a negative impact on women's quality of life for 5–7 years [3, 4].

Hot flashes, as a vasomotor symptom, are accompanied by increased vascular reactivity and are characterized by an initial significant dilation of blood vessels and their subsequent narrowing. The pathogenetic mechanisms of hot flashes are still being studied. Presumably the symptom is the result of a violation of the temperature regulation mechanism in the hypothalamus due to a decrease in estrogen levels after preliminary sensitization to it.

The first line of treatment for hot flashes today is hormone replacement therapy (HRT), which has proven to be effective and have a positive impact on quality of life for many women [5, 6]. However, recent studies, including data from the Women's Health Initiative (WHI) [7, 8], show the unsafety of HRT in some cases. Selective estrogen receptor modulators (SERMs) that have antiestrogenic effects, such as tamoxifen and raloxifene, can also cause hot flashes, which are especially severe in women undergoing treatment for breast cancer [9].

Due to the high need for non-hormonal treatments for vasomotor symptoms, today the possibilities of using non-pharmaceutical methods and drugs from other groups are being actively studied. Specifically, a review of the literature shows that treatment with selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) or serotonin and norepinephrine (SNRIs) reduces the frequency and severity of hot flashes in menopausal and postmenopausal women. Studies have demonstrated the high effectiveness of SSRIs such as paroxetine, citalopram and escitolapram, as well as the SNRI venlafaxine.

Two papers, “Hot flashes and night sweats in menopause: the current state of the issue” by D. F. Archer et al. [10], and “Do SSRIs and SNRIs Reduce the Frequency and/or Severity of Hot Flashes in Menopause” by Chris Stubbs et al.[11] They comprehensively consider the features of the pathogenesis of vasomotor symptoms, the limitations of classical therapy and the possibility of using other methods as its alternative.

Prevalence and general characteristics of hot flashes

As noted in the work of Chris Stubbs, between 80% and 90% of women experience hot flashes during perimenopause and menopause. Archer et al. They also claim that vasomotor symptoms during menopause are recorded in all regions of the world. However, the distribution of symptoms and the need for treatment varies significantly among women of different ethnic backgrounds and from different cultural backgrounds [12, 13]. Vasomotor symptoms are multidimensional and reflect a combination of heredity, diet, physical changes, medications, cultural influences, and individual experiences and expectations. [13]

Hot flashes can occur at any time of the day, they can be spontaneous or triggered by a variety of common factors such as embarrassment, sudden changes in ambient temperature, stress, alcohol, caffeine or any warm drink. Hot flashes usually begin with a sudden sensation of heat or warmth and are often accompanied by sweating, some redness of the skin, and sometimes a feeling of palpitations. The duration varies from 30 seconds to 60 minutes, with an average of 3 to 4 minutes [10].

For most women, hot flashes continue for more than 1 year and last about 4 years on average. Some women continue to experience hot flashes 20 years or more after their last menstrual period [2]. Hot flashes can interfere with work and daily activities, as well as sleep, causing subsequent fatigue, loss of concentration and symptoms of depression, which together interfere with family life, as well as sexual function and relationships between partners.

Mechanisms of the occurrence of tides

Dr. Archer et al. in their work they consider the modern theory of the pathogenesis of hot flashes.

Vasomotor symptoms result from disruption of thermoregulatory function in which normal heat dissipation mechanisms are inappropriately activated. It is generally accepted that the most important region of the brain for thermoregulatory balance is the preoptic area of the hypothalamus [14]. Core body temperature is usually maintained within the thermoneutral zone. When body temperature exceeds a certain limit, afferent pathways are activated in the preoptic zone, dilating blood vessels and increasing sweating [14-16]. When body temperature drops below a certain limit, peripheral blood flow is reduced and shivering occurs [17]. According to the current hypothesis, in women with vasomotor symptoms, the thermoneutral zone is significantly reduced, and afferent pathways are activated even with minor changes in core body temperature.

The most effective treatment for vasomotor symptoms is estrogen therapy. Estrogen is thought to correct the disruption of thermoregulatory function that occurs as a result of fluctuations and decreases in endogenous estrogen during the menopausal transition. Estrogen increases the sweat limit and expands the thermoneutral zone [18].

Scientific evidence suggests that serotonin and norepinephrine play an important role in the pathogenesis of vasomotor symptoms. Fluctuations in estrogen levels alter the levels of norepinephrine and/or serotonin involved in neurotransmission, leading to inappropriate sweating and hot flashes, characteristic of vasomotor symptoms [19-21]. Administration of estradiol results in an overall increase in the synthesis and availability of norepinephrine and serotonin, and also decreases the number, density, or sensitivity of receptors in animal models. Preclinical studies have shown that changes in monoamine neurotransmission can alter the limits of sweating and shivering and narrow the thermoneutral zone.

Hormone replacement therapy (HRT)

As noted by the authors of the paper “Hot flashes and night sweats in menopause: the current state of the issue,” hormonal therapy can effectively control hot flashes and many other common symptoms caused by menopause [22, 23]. Double-blind randomized controlled trials show that no other medical or alternative treatment provides greater relief of vasomotor symptoms than HRT. The effect develops within a month, and within 3 months therapy eliminates up to 90% of all vasomotor symptoms [24]. It is common clinical practice to adjust the dose of HRT to achieve greater effect and minimize side effects such as breast pain or uterine bleeding.

There is an increased risk of thromboembolism with oral HRT, but it has not yet been determined whether non-oral routes of administration such as patches and gels are associated with an increased risk. The type of progestin may also influence risk [25]. However, for those patients who have risk factors (eg, obesity or a history of thromboembolism), the use of non-oral HRT should be considered [6, 25].

There has not been extensive research into the long-term safety and effectiveness of so-called “bioidentical” or “natural” steroid hormones and should be avoided [6]. Locally produced “bioidentical” hormones are not subject to scrutiny by pharmaceutical regulators in many countries, and manufacturers may avoid having to test their products for quality, safety and effectiveness.

Selective estrogen receptor modulators

Selective estrogen receptor modulators (SERMs) have a broad spectrum of activity as estrogen receptor agonists or antagonists, depending on the level of expression of coregulator proteins present in the target tissue. As a class, all recent SERMs share the inability to suppress vasomotor symptoms and may even enhance them compared to placebo. In a recent report, more patients treated with bazedoxifene (23%) experienced hot flashes compared to placebo (6.6%). In most cases, hot flashes were mild or moderate in severity and did not lead to study discontinuation [26]. These results limit the use of SERMs to patients with severe vasomotor symptoms.

Bazedoxifene provides greater endometrial protection than other SERMs. This allows this drug to be used in conjunction with CEE to avoid the negative effects of estrogen on the endometrium and mammary glands, while at the same time suppressing vasomotor symptoms and maintaining normal vaginal health and normal bone mineral density [27].

Non-hormonal therapy for hot flashes

Although hormone replacement therapy is considered the gold standard for the treatment of hot flashes, it is associated with an increased risk of developing estrogen-related pathologies, including breast cancer, endometrial cancer, cardiovascular disease and thromboembolism, Dr. Stubbs notes in his work [11].

Patients with hot flashes who are either unable or unwilling to take HRT turn to non-hormonal treatments. Non-hormonal therapy includes non-pharmaceutical and pharmaceutical agents.

Non-pharmaceutical treatments

- Cognitive behavioral therapy. Psychological interventions for menopause aim to relieve symptoms by influencing behavior, understanding, cognition (memory, beliefs) or emotions [28]. Behavioral intervention techniques include paced breathing (slow, deep breathing), muscle relaxation, and biofeedback. A comparative study showed that paced breathing significantly reduced the frequency of hot flashes, but muscle relaxation and biofeedback did not have such an effect [29]. This effect of paced breathing was confirmed by the same researchers in a placebo-controlled study.

- Acupuncture. The effects of the method on vasomotor symptoms have been studied extensively, but the quality of the studies varies. Randomized controlled trials have found no evidence of effectiveness [30]. A multicenter randomized controlled trial of 267 women showed significant improvements in vasomotor, somatic, and sleep symptoms in women treated with acupuncture plus self-help counseling compared with self-help alone [31]. In summary, acupuncture may reduce menopausal symptoms, but robust clinical studies are needed.

- Blockade of the stellate ganglion. The stellate ganglion is a sympathetic ganglion located directly beneath the subclavian artery, and its intervention has various clinical applications. The ganglion is directly connected to the insular region of the brain, which has high activity during hot flashes [32]. A 12-week pilot study of 13 breast cancer patients experiencing severe hot flashes showed a significant and rapid reduction in the frequency of hot flashes, with very severe hot flashes reduced to virtually nothing. Complications associated with MH block include oculosympathetic paralysis (Horner's syndrome), the need for arterial or venous injection of anesthetic, pneumothorax, and vocal cord paralysis. Pulsed radiofrequency may provide more permanent damage to the stellate ganglion and is not associated with Horner's syndrome [33]. MH blockade may be useful for treating hot flashes in extreme cases where hormonal therapy is contraindicated.

- Yoga. A systematic study of yoga [34] in relation to menopausal symptoms showed that there is insufficient evidence to suggest that yoga is an effective treatment for menopause.

- Phytoestrogens. Large randomized controlled trials have not confirmed that phytoestrogens, red clover isoflavone, and black cohosh are superior to placebo in reducing hot flashes [35]. All major scientific, clinical, and women's health regulatory agencies do not recommend the prescription or use of these hormones.

Archer et al. Their paper summarizes that there is little evidence that changes in diet, acupuncture or exercise reduce hot flashes, but they may improve mood and quality of life. Regular exercise, weight loss, and eliminating triggers of hot flashes (such as caffeine or direct exposure to heat) can help minimize hot flashes and their impact [36]. Meditation, relaxation, controlled breathing, and cognitive behavioral therapy show promising results in reducing hot flashes. Recent level 1 evidence suggests that mindfulness-based therapy may be an effective and well-tolerated treatment for hot flashes [37].

Stubbs et al. confirm that, although potentially effective, non-pharmaceutical methods may not be the best option for women with severe hot flashes or those seeking immediate relief.

Placebo

Interestingly, the use of placebo for menopausal hot flashes has a fairly high subjective effectiveness. The work of Archer et al. reports the results of various studies, according to which the placebo effect ranges from 10 to 63% [35]. However, studies that used outpatient skin conductance sensors to objectively measure physiological hot flashes show that in outpatient settings, women underestimated their true number of hot flashes by 50% [38, 39]. This result calls into question the validity of patient-reported hot flashes as an indicator of the frequency of physiological hot flashes. Although subjective hot flashes may be considered to be more clinically significant than objective hot flashes, one clinical study reported improvements in quality of life, sleep, and fatigue only in women who experienced at least a 50% reduction in objective hot flashes [40].

Pharmaceutical non-hormonal treatments for hot flashes

Many women refuse to use HRT for hot flashes or have contraindications to HRT. Insufficient understanding of the mechanisms underlying menopausal vasomotor symptoms limits the development of new targeted treatments. Existing non-hormonal agents have come to the attention of clinicians due to anecdotal observations of a reduction in the severity of hot flashes as a “side” effect of a drug prescribed for other indications.

Prospective randomized controlled trials have shown that a number of drugs are superior to placebo in the treatment of vasomotor symptoms. In general, these drugs reduce the frequency and severity of hot flashes by 50–60%. This effectiveness is acceptable for most women who do not want to use hormones. In comparison, a standard dose of estrogen reduces hot flashes by 80–90% [10].

As reported by Stubbs et al., several nonestrogenic pharmaceutical or prescription medications have been considered for the treatment of hot flashes. These include the alpha-adrenergic agonist clonidine, the anticonvulsant gabapentin, selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs), and serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors (SNRIs). Clonidine and gabapentin have shown some effectiveness, but each has serious side effects that may make them impractical for many women. Gabapentin causes dizziness, drowsiness, peripheral edema, loss of balance, and suicidal ideation. Side effects from clonidine are similar and include dizziness, sedation, and headache. SSRIs and SNRIs have shown promise in reducing both the frequency and severity of hot flashes without the serious risks associated with HRT or the more serious side effects of other prescription medications studied.

Clinical efficacy of SSRIs and SSRIs in the treatment of vasomotor symptoms

In the work “Hot flashes and night sweats in menopause: the current state of the issue,” D. F. Archer et al. present the results of recent studies of the use of SSRIs, SNRIs and gabapentin to reduce the frequency and severity of vasomotor symptoms [41].

- Prospective, randomized, placebo-controlled trials assessed the effectiveness of the SNRI desvenlafaxine and the results were submitted for regulatory approval [42–44]. With desvenlafaxine 100 mg/day, a 65% reduction in the incidence of vasomotor symptoms was observed at 12 weeks. Of the 75% of patients who achieved remission and improvement, 50% were on desvenlafaxine compared with 29% on placebo, which was statistically significant [43].

- A small comparative study of subcutaneous gabapentin and estradiol found that both drugs reduced the frequency of hot flashes, with no difference between the two study arms [45]. Gabapentin (300 mg three times daily) was as effective as low-dose estrogen in reducing the frequency and severity of vasomotor symptoms. Venlafaxine extended release (75 mg) was not directly compared with estrogen, but was as effective as gabapentin in treating vasomotor symptoms and was better tolerated in one crossover study [46].

- In one prospective study [47], fluoxetine and citalopram did not reduce hot flashes compared with placebo, while in another study [48], paroxetine, venlafaxine, fluoxetine, and sertraline were more effective than placebo.

Drugs that affect serotonin and norepinephrine levels in the brain have demonstrated modest effects on vasomotor symptoms. Desvenlafaxine, which is approved in Mexico and Thailand for the treatment of vasomotor symptoms at a dose of 100 mg/day, is recommended to titrate with a gradual increase in dose to minimize adverse events (nausea, vomiting, dizziness) in the first week after initiation of therapy and with a decrease in dose to minimize withdrawal symptoms (anxiety, depression and sudden mood swings).

The authors of the paper “Do SSRIs and SNRIs Reduce the Frequency and/or Severity of Hot Flashes in Menopause” by Chris Stubbs cite the results of several large-scale reviews:

In 2013, Shams et al. published a systematic review and meta-analysis assessing the effectiveness of five SSRIs—escitalopram, paroxetine, sertraline, citalopram, and fluoxetine—for reducing vasomotor symptoms (hot flashes) in healthy perimenopausal women. An analysis of 11 randomized controlled trials (RCTs) involving a group of 2069 women aged 36 to 76 years showed that treatment with SSRIs led to a significant reduction in the average number of daily hot flashes over 4-8 weeks from 10 per day to 9 compared with placebo. In this study, escitolapram was the most effective SSRI for reducing the daily frequency of hot flashes. The researchers concluded that SSRIs are a reasonable replacement for HRT. [49]

A 2015 systematic review by Handley and Williams analyzed 18 RCTs examining the effectiveness of SSRIs/SNRIs compared with placebo. Participants were healthy women aged 27 to 78 years who reported experiencing an average of 46 to 76 hot flashes per week. SSRIs/SSRIs reduced hot flash symptoms by 65% compared with placebo. Potential first-line SSRIs included paroxetine, extended-release paroxetine, citalopram and escitalopram). Venlafaxine has been identified as a potential first-line SNRI. Extended-release paroxetine showed the greatest statistically significant reduction in hot flashes. Venlafaxine provided more rapid symptom relief than SSRIs, but had a higher incidence of side effects , most notably nausea and constipation. [50]

In 2015, the North American Menopause Society (NAMS) published a statement on non-hormonal management of vasomotor symptoms associated with menopause [23]. Team members searched five databases for high-quality evidence articles (RCTs or systematic reviews) on non-hormonal treatments for hot flashes. One such study reported that the SNRI venlafaxine extended-release formulation demonstrated similar efficacy to low-dose estradiol in reducing vasomotor symptoms. After assessing the evidence, the NAMS panel concluded that non-hormonal treatments are appropriate treatments for hot flashes in menopause and postmenopause.

NAMS recommendations include the following SSRIs and SNRIs: paroxetine salt 7.5 mg/day; paroxetine or delayed-release paroxetine 10-25 mg/day; escitalopram 10-20 mg/day; citalopram 10-20 mg/day; desvenlafaxine 50-150 mg/day; and venlafaxine in extended-release form 37.5–150 mg/day. Paroxetine salt is only available in a 7.5 mg dosage and is currently the only FDA-approved medication for hot flashes [23].

Women with a history of breast cancer taking tamoxifen should avoid SSRIs. Studies have shown that some SSRIs inhibit the activity of the CYP2D6 enzyme, which may result in decreased therapeutic levels of tamoxifen. The SNRIs venlafaxine and desvenlafaxine appear to have little or no effect on the activity of tamoxifen and should be considered as first-line therapy in these patients. [eleven]

Conclusion

Vasomotor symptoms occur in all women, regardless of their cultural and ethnic background, and often negatively affect the quality of life of patients.

HRT is still considered the most effective treatment for reducing hot flashes in menopausal and postmenopausal women. However, concerns that hormonal therapy may increase the risk of estrogen-related pathologies have led to research into the possibility of using other agents to treat this pathology. Non-pharmaceutical methods and some pharmaceutical drugs, in particular the SERM group, do not convincingly demonstrate their effectiveness.

SSRIs and SNRIs reduce the frequency and severity of vasomotor symptoms associated with menopause by 10% to 64%, depending on the study. Side effects from SSRIs and SNRIs, including nausea, constipation and dry mouth, were not severe and often resolved within the first week. [4, 23]

From the SSRI group, escitalopram and prolonged-release paroxetine show the greatest activity, from the SNRI group - venlafaxine in a prolonged form.

Although SSRIs and SNRIs are less effective than HRT, they significantly reduce the frequency and severity of hot flashes and may be recommended for women who are not willing to accept the risks of hormonal therapy. Additional placebo-controlled studies are needed to evaluate benefits, safety, and dosing in more detail.

Literature:

- Voda AM. Climacteric hot flash. Maturitas 1981;3:73–90

- Politi MC, Schleinitz MD, Col NF. Revisiting the duration of vasomotor symptoms of menopause: a meta-analysis. J Gen Intern Med 2008; 23:1507-13

- Freedman RR. Menopausal hot flashes: mechanisms, endocrinology, treatment. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol. 2014; 142:115–20. [PubMed: 24012626]

- Imai A, Matsunami K, Takagi H, Ichigo S. New generation nonhormonal management for hot flashes. Gynecol Endocrinol. 2013; 29(1):63–6. [PubMed: 22809093]

- Santen RJ, Allred DC, Ardoin SP, et al. Postmenopausal hormone therapy: an Endocrine Society scientific statement. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2010;95:s1–66

- Sturdee DW, Pines A, on behalf of the International Menopause Society Writing Group. Updated IMS recommendations on postmenopausal hormone therapy and preventive strategies for midlife health. Climacteric 2011;14:302–20

- LaCroix AZ, Chlebowski RT, Manson JE, et al. Health outcomes after stopping conjugated equine estrogens among postmenopausal women with prior hysterectomy: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA 2011;305:1305–14

- Rossouw JE, Anderson GL, Prentice RL, et al. Risks and benefits of estrogen plus progestin in healthy postmenopausal women: principal results from the Women's Health Initiative randomized controlled trial. JAMA 2002;288:321–33

- Gupta P, Sturdee DW, Palin SL, et al. Menopausal symptoms in women treated for breast cancer: the prevalence and severity of symptoms and their perceived effects on quality of life. Climacteric 2006;9:49–58

- Archer DF, Sturdee DW, Baber R, et al. Menopausal hot flushes and night sweats: where are we now?. Climacteric. 2011;14(5):515-528. doi:10.3109/13697137.2011.608596

- Stubbs, Chris & Mattingly, Lisa & Crawford, Steven & Wickersham, Elizabeth & Brockhaus, Jessica & McCarthy, Laine. (2017). Do SSRIs and SNRIs reduce the frequency and/or severity of hot flashes in menopausal women. The Journal of the Oklahoma State Medical Association. 110. 272-274.

- Freeman EW, Sherif K. Prevalence of hot flushes and night sweats around the world: a systematic review. Climacteric 2007;10:197–214

- Palacios S, Henderson VW, Siseles N, Tan D, Villaseca P. Age of menopause and impact of climacteric symptoms by geographical region. Climacteric 2010;13:419–28

- Romanovsky A.A. Thermoregulation: some concepts have changed. Functional architecture of the thermoregulatory system. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 2007;292:R37–46

- Boulant JA. Role of the preoptic-anterior hypothalamus in thermoregulation and fever. Clin Infect Dis 2000;31(Suppl 5):S157–61

- Zhang YH, Yamada K, Hosono T, Chen XM, Shiosaka S, Kanosue K. Efferent neuronal organization of thermoregulatory vasomotor control. Ann NY Acad Sci 1997;813:117–22

- Charkoudian N. Skin blood flow in adult human thermoregulation: how it works, when it does not, and why. Mayo Clin Proc 2003;78:603–12

- Freedman RR, Blacker CM. Estrogen raises the sweating threshold in postmenopausal women with hot flashes. Fertil Steril 2002;77:487–90

- Berendsen HH. The role of serotonin in hot flushes. Maturitas 2000;36:155–64

- Quan N, Xin L, Blatteis CM. Microdialysis of norepinephrine into preoptic area of guinea pigs: characteristics of hypothermic effect. Am J Physiol 1991;261:R378–85

- Freedman RR. Pathophysiology and treatment of menopausal hot flashes. Semin Reprod Med 2005;23:117–25

- MacLennan AH. Evidence-based review of therapies at the menopause. Int J Evid Based Healthc 2009;7:112–23

- Nonhormonal management of menopause-associated vasomotor symptoms: 2015 position statement of The North American Menopause Society. Menopause. 2015; 22(11):1–18. [PubMed: 25490113]

- MacLennan AH, Broadbent JL, Lester S, Moore V. Oral oestrogen and combined oestrogen/progestogen therapy versus placebo for hot flushes. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (Online) 2004:CD002978

- Olié V, Canonico M, Scarabin PY. Postmenopausal hormone therapy and venous thromboembolism. Thromb Res 2011;127(Suppl 3):S26–9

- de Villiers TJ, Chines AA, Palacios S, et al. Safety and tolerability of bazedoxifene in postmenopausal women with osteoporosis: results of a 5-year, randomized, placebocontrolled phase 3 trial. Osteoporos Int 2011;22:567–76

- Lobo RA, Pinkerton JV, Gass ML, et al. Evaluation of bazedoxifene/conjugated estrogens for the treatment of menopausal symptoms and effects on metabolic parameters and overall safety profile. Fertil Steril 2009;92:1025–38

- Towey M, Bundy C, Cordingley L. Psychological and social interventions in the menopause. Curr Opin Obstet Gynecol 2006;18:413–17

- Freedman RR, Woodward S. Behavioral treatment of menopausal hot flushes: evaluation by ambulatory monitoring. Am J Obstet Gynecol 1992;167:436–9

- Lee MS, Shin BC, Ernst E. Acupuncture for treating menopausal hot flushes: a systematic review. Climacteric 2009;12:16–25

- Borud EK, Alraek T, White A, et al. The acupuncture on hot flushes among menopausal women (ACUFLASH) study, a randomized controlled trial. Menopause 2009;16:484–93

- Freedman RR, Benton MD, Genik RJ, et al. Cortical activation during menopausal hot flashes. Fertil Steril 2006;85:674–678

- van Boxem K, van Eerd M, Brinkhuize T, et al. Radiofrequency and pulsed radiofrequency treatment of chronic pain syndromes: the available evidence. Pain Pract 2008;8:385–93

- Lee MS, Kim JI, Ha JY, Boddy K, Ernst E. Yoga for menopausal symptoms: a systematic review. Menopause 2009;16:602–8

- Geller SE, Shulman LP, van Breemen RB, et al. Safety and efficacy of black cohosh and red clover for the management of vasomotor symptoms: a randomized controlled trial. Menopause 2009;16:1156–66

- Borrelli F, Ernst E. Alternative and complementary therapies for the menopause. Maturitas 2010;66:333–43

- Carmody JF, Crawford S, Salmoirago-Blotcher E, Leung K, Churchill L, Olendzki N. Mindfulness training for coping with hot flashes: results of a randomized trial. Menopause 2011;18:611–20

- Carpenter JS, Elam JL, Ridner SH, Carney PH, Cherry GJ, Cucullu HL. Sleep, fatigue, and depressive symptoms in breast cancer survivors and matched healthy women experiencing hot flashes. Oncol Nurs Forum 2004;31:591–8

- Carpenter J, Azzouz F, Monahan P, Storniolo A, Ridner S. Is external skin conductance monitoring a valid measure of hot flash intensity or distress? Menopause 2005;12:512–19

- Carpenter JS, Storniolo AM, Johns S, et al. Randomized, double-blind, placebocontrolled crossover trials of venlafaxine for hot flashes after breast cancer. Oncologist 2007;12:124–35

- Albertazzi P. Non-estrogenic approaches for the treatment of climacteric symptoms. Climacteric 2007;10(Suppl 2):115–20

- Archer DF, Seidman L, Constantine GD, Pickar JH, Olivier S. A double-blind, randomly assigned, placebo-controlled study of desvenlafaxine efficacy and safety for the treatment of vasomotor symptoms associated with menopause. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2009;200:172 e1–10

- Speroff L, Gass M, Constantine G, Olivier S. Efficacy and tolerability of desvenlafaxine succinate treatment for menopausal vasomotor symptoms: a randomized controlled trial. Obstet Gynecol 2008;111:77–87

- Archer DF, Dupont CM, Constantine GD, Pickar JH, Olivier S. Desvenlafaxine for the treatment of vasomotor symptoms associated with menopause: a double-blind, 35 randomized, placebo-controlled trial of efficacy and safety. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2009;200:238 e1–10

- Aguirre W, Chedraui P, Mendoza J, Ruilova I. Gabapentin vs. low-dose transdermal estradiol for treating post-menopausal women with moderate to very severe hot flushes. Gynecol Endocrinol 2010;26:333–7

- Loprinzi CL, Sloan J, Stearns V, et al. Newer antidepressants and gabapentin for hot flashes: an individual patient pooled analysis. J Clin Oncol 2009;27:2831–7

- Suvanto-Luukkonen E, Koivunen R, Sundstrom H, et al. Citalopram and fluoxetine in the treatment of postmenopausal symptoms: a prospective, randomized, 9-month, placebocontrolled, double-blind study. Menopause 2005;12:18–26

- Loprinzi CL, Sloan J, Stearns V, Iyengar M, et al. Newer antidepressants and gabapentin for hot flashes: an individual patient pooled analysis. J Clin Oncol 2009;27:2831– 7

- Shams T, Firwana B, Habib F, et al. SSRIs for hot flashes: a systematic review and meta analysis of randomized trials. J Gen Intern Med. 2013; 29(1):204–13. [PubMed: 23888328]

- Handley A, Williams M. The efficacy and tolerability of SSRI/SNRIs in the treatment of vasomotor symptoms in menopausal women: a systematic review. J Am Assoc Nurse Pract. 2015; 27(1):54–61. [PubMed: 24944075]

Prevention

In hot weather, it is necessary to wear a hat.

Specific preventive measures regarding redness and heat on the face have not been developed. It all depends on what specific disease they should be aimed at.

General preventive measures:

- wearing a hat in sunny weather;

- using sunscreen before going outside;

- use of cosmetics suitable for your skin type;

- avoiding exposure to frost or cold winds;

- maintaining proper nutrition and lifestyle in general.

A hot head, if such a phenomenon is observed in isolated cases, is not a reason to see a doctor. If the symptom is present frequently or on an ongoing basis, it is better to undergo a comprehensive examination.