About the treatment of multiple sclerosis. Interferons

Interferons (IFNs) are a group of biologically active proteins (glycoproteins) produced by various cells of the body in response to a viral infection or exposure to certain chemical and biological substances. The binding of interferons to cellular receptors leads to a significant positive effect.

A number of intracellular proteins are produced, which:

- have an antiviral effect ;

- stabilize the immune system ( immunomodulation);

- controls cell division ( antiproliferation); .

There are alpha, beta, and gamma interferons.

Interferon beta is recognized as the most effective in the treatment of MS . Their use reduces the number of exacerbations and slows down the development of the disease.

interferon beta drugs is to suppress the formation in the human body of substances that damage the myelin sheath of nervous tissue. At the same time, interferons promote the activation of other cells that reduce the effect of antibodies to myelin , thereby reducing the activity of the inflammatory process.

In addition, beta interferons protect myelin layers from further destruction, and also reduce the likelihood of damage to the blood-brain barrier (BBB) , preventing the penetration of immune complexes into brain cells.

There are two types of beta interferons:

- Interferon beta-1b;

- Interferon beta-1a.

The main clinical effects of drugs from both groups include:

- reduction in the average annual frequency of exacerbations;

- slowdown in disability (increase in EDSS);

- improving the quality of life of patients[xvii].

interferon preparations are administered by the patient independently subcutaneously or intramuscularly, after prescription and recommendations from a doctor. Injections of the drug are quite low-traumatic and do not cause difficulties to the patient. As a rule, courses of interferon are long. Since unjustified cessation of interferon beta treatment leads to a return of symptoms of multiple sclerosis, its cessation is justified only if the drug is not sufficiently effective or serious side effects develop as a result of treatment.

Due to the fact that interferon are involved in the activation of the body's defenses , after administration, reactions reminiscent of a “cold” (flu-like syndrome) may develop, as well as local reactions in the injection area in the form of itching, redness and swelling.

contraindications for treatment with interferon beta :

- pregnancy;

- hypersensitivity to the drug;

- therapy with anticonvulsants.

Interferon beta therapy is currently used throughout the world to treat relapsing and secondary progressive forms of multiple sclerosis[xix].

Studies have shown that long-term use of interferon beta is quite safe and effective. The use of the drug in adults with relapsing-remitting and progressive forms of multiple sclerosis reduced the frequency of exacerbations, the severity of symptoms and extended the duration of remissions. The formation of new lesions also decreased significantly decreased .

Key words: multiple sclerosis, children, Betaferon.

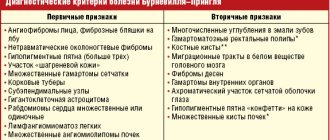

Multiple sclerosis is a chronic progressive disease of the central nervous system that usually affects young and middle-aged people. Clinically, the disease manifests itself as diffuse neurological symptoms with the involvement of several functional systems in the pathological process, which leads to loss of performance, ability to move and self-care. According to the World Health Organization, among neurological diseases, multiple sclerosis (MS) is the most common neurological cause of permanent disability in young people. In recent years, there has been an increase in the number of patients with multiple sclerosis throughout the world, which is associated, firstly, with improved diagnostic capabilities and, above all, with the widespread introduction of magnetic resonance imaging into medical practice, and secondly, with an increase in life expectancy against the background specific treatment, thirdly, with a true increase in incidence. In Russia, on average, multiple sclerosis occurs with a frequency of 30 to 100 cases per 100,000 population. It is noteworthy that just 20 years ago, in medical circles, multiple sclerosis was viewed as an exclusively adult disease. However, in recent years it has become obvious that multiple sclerosis also occurs in childhood. Epidemiological studies conducted in Russia and abroad have shown that in 5-10% of patients, multiple sclerosis manifests itself before the age of 18 years [1, 2]. Questions of the etiology and etiotropic treatment of this disease remain open to this day. In recent years, the multifactorial etiology of multiple sclerosis has become increasingly recognized, based on which the main role in the development of the disease is given to the influence of external factors on genetically predisposed individuals. It is assumed that a combination of external and genetic factors can lead to the development of inflammatory and immunopathological reactions, which are accompanied by immunological and biochemical changes in both the central nervous system and the body as a whole. Studies conducted at the Research Institute of Pediatrics of the Scientific Center for Children's Diseases of the Russian Academy of Medical Sciences (Dir. Academician of the Russian Academy of Medical Sciences A.A. Baranov) showed that multiple sclerosis in childhood has its own clinical features in the form of a predominance of symptoms of damage to the pyramidal tract and brain stem, with relatively rare sensory and pelvic violations. In case of optic neuritis, an unfavorable prognosis is caused by the early development of secondary atrophy of the optic nerves. One of the main differences between multiple sclerosis with its onset in childhood, despite the high frequency of detected “giant” lesions, is the slower formation of irreversible degenerative changes, both according to MRI (local and diffuse atrophy of the brain substance) and clinical (dissociation between the volume focal brain damage and the severity of neurological disorders). The presence of moderate clinical manifestations with a large number of lesions on MRI indicates great opportunities for compensation of impaired functions in childhood. The distribution curve of patients by age of onset of multiple sclerosis depending on gender showed a predominance of boys in the age group from 3 to 5 years, and a clear predominance of girls in the age group from 10 to 13 years [3, 22]. In more than 97% of pediatric patients, multiple sclerosis debuts in the form of a relapsing-remitting type of disease [3]. The long-term prognosis of disease progression in this category of patients remains a subject of debate, however, retrospective studies have shown that despite the longer average period of time from the onset of multiple sclerosis to the achievement of persistent neurological disability, in general, compared with adult patients at the time of the formation of irreversible neurological deficit, patients with pediatric onset of the disease are younger than patients who became ill after 18 years of age [3]. Since multiple sclerosis is a heterogeneous disease in terms of its development mechanism and types of clinical course, therapy is differentiated. Within the framework of the existing concept of the pathogenesis of multiple sclerosis, today the most effective pathogenetic treatment is immunomodulatory therapy, the appearance of which in the clinical practice of a neurologist has changed therapeutic approaches to a pathology previously considered incurable, and has made it possible to actually reduce the frequency of exacerbations in relapsing-remitting and secondary progressive courses. multiple sclerosis. Medicines, so-called “course-modifying drugs for multiple sclerosis,” reduce the frequency of exacerbations of multiple sclerosis by an average of 30% and, to varying degrees, slow the rate of progression of irreversible disorders leading to disability. They have long been widely used in adult patients with multiple sclerosis, especially at the stage of relapsing-remitting disease. The safety and tolerability of immunomodulatory drugs have been well studied, but all major studies conducted in this area have included patients over 18 years of age. One of the leading modern principles of immunomodulatory treatment of MS is the earliest possible initiation of therapy for patients with a relapsing-remitting type of the disease [14]. The advisability of using drugs for immunomodulatory treatment of multiple sclerosis has been proven even before a reliable diagnosis is made in patients after the first demyelinating episode or the so-called clinically isolated syndrome, with a high risk of progression according to MRI [15]. Immunomodulatory drugs include beta interferons. Their use makes it possible to reduce the frequency and severity of exacerbations of multiple sclerosis by a third; during treatment, a decrease in the number of inflammatory foci in the central nervous system was noted by 50-80%; in addition, the use of beta interferons has a positive effect on cognitive functions and the quality of life of patients in general. Currently, interferons are considered as the drugs of choice in the treatment of relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis, and their successful use in clinically isolated syndrome has also begun. Interferons beta are also used in secondary progressive multiple sclerosis, since in this case they slow down disability and reduce the formation of new lesions on MRI. The main side effects of interferons: flu-like symptoms (fever, chills, malaise, muscle pain and fatigue) develop in approximately half of all patients at the beginning of treatment, but subsequently disappear. Local reactions, moderate thrombocytopenia and anemia, depressive episodes, and increased transaminase concentrations are less common. In some cases, the use of interferons may be accompanied by the formation of neutralizing antibodies. Treatment with interferons is carried out for a long time, its termination is justified only in case of obvious ineffectiveness (exacerbations more than 4 times a year or progression of disability by 1 point on the EDSS scale in 6 months) and if side effects develop. Interferons beta have antiviral and immunomodulatory activity. It is known that the biological effect of these drugs is mediated by their interaction with specific receptors that are found on the surface of human cells. The binding of interferon beta to these receptors induces the expression of a number of substances that are considered to mediate the biological effects of interferon beta. Beta interferons reduce the binding capacity and expression of interferon gamma receptors and enhance their degradation. In addition, they have the ability to increase the suppressor activity of peripheral blood mononuclear cells and, by blocking matrix metalloproteinase, stabilize the state of the blood-brain barrier. Interferon beta 1b (Betaferon®), the first of the beta interferons synthesized for the immunomodulatory treatment of multiple sclerosis, is now considered an established drug throughout the world. Among all DMTs, Betaferon has the longest clinical experience of use. To date, ideas about the effectiveness and safety of Betaferon are based on the results of controlled clinical studies involving patients with relapsing-remitting and secondary progressive multiple sclerosis, as well as in patients with clinically isolated syndrome. The experience of using interferon beta 1b in adult neurological practice spans more than 16 years of clinical observation. In 2005, the results of a 16-year prospective multicenter study of 135 adult patients with MS were presented for the first time, in whom the effectiveness and safety of long-term use of this drug was established against the background of continuous immunomodulatory therapy with interferon beta 1b [16]. Clinical studies have shown that the use of Betaferon in adult patients with relapsing-remitting and secondary progressive multiple sclerosis reduces the frequency of clinical exacerbations (after 2 years by 34 and 30%, respectively, compared with the group of patients taking placebo), the severity of relapses, the number of hospitalizations, the need for in treatment with corticosteroids, and also prolongs the duration of remissions. According to magnetic resonance imaging of the brain, in patients with relapsing-remitting and secondary progressive disease during treatment with Betaferon, there is a significant decrease in the formation of new active lesions, and the severity of the pathological process is also reduced. It has been proven that the use of interferon beta 1b in clinically isolated syndrome helps to increase the time until a diagnosis of definite multiple sclerosis is made. In patients with secondary progressive multiple sclerosis, the use of Betaferon can delay the progression of the disease for up to 12 months, even with a significant degree of disability. Currently, there are a number of studies conducted both abroad and in our country devoted to the study of the use of interferon beta 1b (Betaferon) in children and adolescents [5, 17]. The first experience with the use of drugs for immunomodulatory therapy of MS up to 18 years of age published in the literature was a clinical observation conducted by AB Adams et al in 1999, which demonstrated “dramatic” clinical effectiveness (significant reduction in disability and absence of exacerbations throughout treatment), confirmed by dynamic MRI data show a positive experience of long-term (30 months) treatment with interferon beta 1b for a 7-year-old child with relapsing-remitting MS. Considering the lack of experience with the use of interferon beta in children, the dose of the drug was adapted to age: initial - 4 million IU, after a year it was increased to 6 million IU. No systemic or local adverse reactions were observed during treatment. During therapy, a short-term increase in the titer of neutralizing antibodies to interferon beta 1b was recorded in the child, which did not affect the effectiveness of therapy, either clinically or according to MRI data [5]. The next description of the use of interferon beta 1b in children with multiple sclerosis is a study conducted in 2001 by SN Tenembaum et al., who also describe the positive experience of using interferon beta and glatiramer acetate in 19 children with relapsing-remitting and secondary progressive MS with exacerbations (5 children received interferon beta 1b). This publication draws attention to the rationale for the use of “adult” standard doses of interferon beta in children and adolescents, since an attempt to reduce the dose of the drug in the study (“adaptation” to age) reduced the clinical effectiveness of therapy. In domestic literature in 2004 by authors N.A. Totolyan and A.A. Skoromets used the example of 5 clinical cases to illustrate his own experience in prescribing interferon beta 1b for up to 18 years of age. The obtained clinical observation data were analyzed by the researchers and a number of reasoned conclusions were proposed:

1) on the advisability of prescribing drugs for immunomodulatory therapy as early as possible for children and adolescents with MS, especially with high disease activity, characterized by a high frequency of exacerbations (2 or more exacerbations during the first year from the onset of MS); 2) given the limited data on the safety of the use of beta interferons in childhood and adolescence, it is recommended to begin this type of therapy in a hospital setting, monitoring changes in biochemical and hematological parameters (for example, the number of blood leukocytes, the activity of liver enzymes, the level of creatinine in the blood serum); 3) expected systemic and local side effects when prescribing beta interferons require prevention (for example, moving the injection of the drug to the evening) and, if necessary, correction (for example, prescribing non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs);

4) in most cases, children are shown standard doses of beta interferons, however, to reduce the severity and duration of influenza-like syndrome, it is advisable to titrate the dose of the drug at the beginning of treatment; 5) therapy with interferon beta drugs should be continuous and long-term, since unreasonable cessation of treatment entails significant decompensation of the immunopathological process [17].

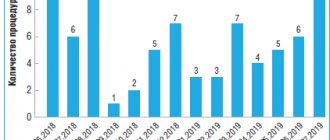

In 2006, the results of the first international multicenter retrospective study of the safety and tolerability of interferon beta 1b in children and adolescents with MS were published, based on the results of observation of patients who received at least one injection of interferon beta 1b before 18 years of age, collected up to 2004 inclusive. The study made it possible to systematize scattered data on the experience of using interferon beta 1b in pediatrics. The study included 43 pediatric patients with relapsing-remitting MS from 8 medical centers in the USA, Canada, Argentina, Turkey, Russia and Germany. After the final processing of the data obtained, only 39 patients met the diagnostic criteria for reliable MS [18, 19], in whom the final analysis of the effectiveness of treatment was carried out, and the results of observation of 4 children not included in this group were used to assess the tolerability of therapy. The average duration of immunomodulatory treatment was 29.2 months, and the average age of patients at the time of initiation of therapy was 13 ± 3.0 years. The clinical effectiveness of immunomodulatory therapy was confirmed by a decrease in the average EDSS score from 2.5 (from 0 to 8.5) to 2.0 (from 0 to 6.5) and a 50% reduction in the average annual frequency of exacerbations (the dynamics of the indicator was assessed in 32 children who received treatment for 12 months or more). To objectify the statistical processing of data on the safety and tolerability of therapy in a heterogeneous group of patients by age, all patients were conditionally divided into a subgroup of children under 10 years of age inclusive (8 patients) and a subgroup of adolescents from 11 to 17 years 10 months (35 patients). It should be noted that in the subgroup of children under 10 years of age, more laboratory abnormalities associated with the activity of liver enzymes were recorded, which apparently influenced the increase in the number of adverse reactions in the younger group as a whole (87.5% compared to 62. 9% in older patients). Based on the spectrum, frequency and severity of clinical adverse reactions (influenza-like syndrome in 35% of patients, local reactions in 21% of patients) and changes in laboratory parameters (increased activity of liver transaminases in 26% of patients), and none of the identified side effects was considered as severe or unexpected, the authors concluded that the treatment was well tolerated [20]. At the Scientific Center for Children's Health of the Russian Academy of Medical Sciences (directed by Academician of the Russian Academy of Medical Sciences A.A. Baranov), a clinical observation was carried out of 22 adolescents with relapsing-remitting (18 patients) and secondary progressive (4 patients) multiple sclerosis aged 13 to 17 years, during treatment interferon beta 1b (duration from 2 to 15 months) at a dose of 8 million IU subcutaneously every other day [21]. The effectiveness of therapy in patients was confirmed by a decrease in the average disability score (from 2.56 ± 0.23 to 2.09 ± 0.22 points on the EDSS scale); the number of patients without exacerbations during treatment (13 children - 59%); a decrease in the average annual frequency of exacerbations in 7 patients who received the drug for 12 months or more (from 2 ± 0.37 to 1.14 ± 0.34 exacerbations per year), and the progression rate from 0.69 ± 0.15 before treatment up to 0.45 ± 0.07 after a course of immunomodulatory therapy. During therapy, 12 patients (54%) experienced adverse reactions, represented by influenza-like syndrome in 50% (11 patients), local reactions were observed in 9% (2 patients), and in one teenager (4.5%) changes in biochemical blood parameters - a significant increase in the activity of liver transaminases (more than 10 times), and in one clinical case (4.5%) a depressive episode was observed. In the last two cases, a decision was made to discontinue the drug. The totality of all the data presented above demonstrates the need and advisability of timely administration of drugs for immunomodulatory therapy for both adolescents and children with multiple sclerosis. The results of a study of the natural course of multiple sclerosis in children (67 patients with the onset of the disease before 16 years of age, observed without the use of drugs for immunomodulatory treatment for 4.91 ± 0.58 years), also conducted in 2002 at the Research Institute of Pediatrics of the Scientific Center for Disease Control of the Russian Academy of Medical Sciences, indicate that without therapy, during the first five years from the moment of manifestation of the disease, that is, by the end of the “pediatric” age, almost 100% of patients with early onset of multiple sclerosis develop a persistent neurological deficit with EDSS = 3 points, and about 40% of patients will move into the stage of secondary progression of multiple sclerosis [22]. At the same time, the assumption made by both domestic and foreign authors about high functional plasticity, more intense remyelination and less severe neuronal damage in children was confirmed by data from dynamic MRI observations of children and adolescents with relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis. Thus, based on theoretical data and practical positive experience in the use of DMTRS in pediatric neurological practice, it can be argued that early initiation of immunomodulatory therapy for multiple sclerosis in patients of childhood and adolescence is not only possible, but also necessary, since children and adolescents who have not received timely and adequate treatment, by the time they reach adulthood they will become permanently neurologically disabled.

Recommended reading 1. Duquette P., Murray TJ, Pleines J. et al. Multiple sclerosis in childhood: clinical profile in 125 patients // J Pediatr. 1987; 111: 359-363. 2. Ghezzi A., Deplano V., Faroni J. et al. Multiple sclerosis in childhood: clinical features of 149 cases // Mult Scler. 1997; 3: 43-46. 3. Boiko A., Vorobeychik G., Paty D., Devonshire V., Sadovnick D. Early onset multiple sclerosis: a longitudinal study // Neurology. 2002; 59: 1006-1010. 4. Banwell BL Pediatric multiple sclerosis // Curr Neurol Neurosci Rep. 2004; 4: 245-252. 5. Adams AB, Tyor WR, Holden KR Interferon beta-1b and childhood multiple sclerosis // Pediatr Neurol. 1999; 21: 481-483. 6. Mikaeloff Y., Moreau T., Debouverie M. et al. Interferon-beta treatment in patients with childhood-onset multiple sclerosis // J Pediatr. 2001; 139: 443-446. 7. Waubant E., Hietpas J., Stewart T. et al. Interferon beta-1a in children with multiple sclerosis is well tolerated // Neuropediatrics. 2001; 32: 211-213. 8. Eraksoy M., Demir G., Ozcan H., Bavndir C., Say A., Saruhan G. Multiple Sclerosis in childhood: a prospective study // J Neurol. 1996; 243: 444. 9. Eraksoy M. In: Siva A, Kesselring J, Thompson AJ, eds. Multiple sclerosis in children: a review. London: Martin Dunitz, 1999. 10. Tenembaum S., Segura M., Fejerman N. Tolerability and efficacy of disease-modifying therapies in childhood and juvenile multiple sclerosis // Neurology. 2001; 56:A361. 11. Tenembaum S., Segura M., Fejerman N. Disease-modifying therapies in childhood and juvenile multiple sclerosis // Mult Scler. 2001; 7:S57. 12. Tenembaum S., Segura M. Clinical effects of disease-modifying therapies in early-onset multiple sclerosis // Neurology. 2004; 62:A488. 13. Pohl D., Rostasy K., Gartner J., Hanefeld F. Treatment of early onset multiple sclerosis with subcutaneous interferon beta-1a // Neurology. 2005; 64:888-890. 14. Rieckmann P., Toyka K.V., Bassetti C. et al. Escalating immunotherapy of multiple sclerosis-new aspects and practical application // J Neurol. 2004; 251: 1329-1339. 15. Kappos L., Polman CH, Freedman MS, Edan G., Hartung HP, Miller DH, Montalban X., Barkhof F., Bauer L., Jakobs P., Pohl C., Sandbrink R. Treatment with interferon beta- 1b delays conversion to clinically definite and McDonald MS in patients with clinically isolated syndromes // Neurology. 2006; 67: 1-8. 16. Ebers G., Rice G., Wolf Ch., Traboulsee A., Langdon D., Kaskel P., Salazar-Grueso E. 16-year long-term follow-up of interferon beta-1b treatment of patients with multiple sclerosis. Presented at Congress: 2005: 21st ECTRIMS, Thesaloniki, Greece. 17. Totolian NA, Skoromets AA Interferon-beta treatment in patients with childhood-onset and juvenile multiple sclerosis // Zh Nevrol Psikhiatr Im SS Korsakova. 2004;104(9):23-31. 18. McDonald WI, Compston A, Edan G et al. Recommended diagnostic criteria for multiple sclerosis: guidelines from the International Panel on the diagnosis of multiple sclerosis // Ann Neurol. 2001; 50: 121-127. 19. Poser CM, Paty DW, Scheinberg L. et al. New diagnostic criteria for multiple sclerosis: guidelines for research protocols // Ann Neurol. 1983; 13: 227-231. 20. Banwell B., Reder AT, Krupp L. et al. Safety and tolerability of interferon beta-1b in pediatric multiple sclerosis // Neurology. 2006; 66; 472-476. 21. Bykova O.V., Kuzenkova L.M., Maslova O.I. The use of interferon beta 1b in adolescents with multiple sclerosis // Journal of Neurology and Psychiatry named after. S.S. Korsakova 2006;9: 29-33. 22. Gusev E., Boiko A., Bikova O. et al. The natural history of early onset multiple sclerosis: comparison of data from Moscow and Vacouver // Clin Neurol Neurosurg. 2002, 104: 203-207. 23. Higurashi N., Hamano S., Eto Y. Secondary progressive multiple sclerosis in childhood – interferon beta 1b treatment //To Hattatsu. 2006; 38:3:209-13.

Interferon beta-1b

Recombinant interferon beta-lb is isolated from Escherichia coli cells, into the genome of which the human interferon beta gene is introduced, encoding the amino acid of the series in the 17th position.

Interferon beta-lb is a non-glycosylated protein with a molecular weight of 18,500 daltons, consisting of 165 amino acids. Pharmacodynamics

Interferons are proteins in structure and belong to the cytokine family. The molecular weight of interferons ranges from 15,000 to 21,000 Daltons. There are three main classes of interferons: alpha, beta and gamma. Interferons alpha, beta and gamma have a similar mechanism of action, but different biological effects. The activity of interferons is species-specific, and, therefore, it is possible to study their effects only in human cell cultures or in vivo in humans.

Interferon beta-lb has antiviral and immunomodulatory activities. The mechanism of action of interferon beta-lb in multiple sclerosis has not been fully established. However, it is known that the biological effect of interferon beta-lb is mediated by its interaction with specific receptors that are found on the surface of human cells. The binding of interferon beta-lb to these receptors induces the expression of a number of substances that are considered to mediate the biological effects of interferon beta-lb. The content of some of these substances was determined in the serum and blood cell fractions of patients receiving interferon beta-lb. Interferon beta-lb reduces the binding capacity of the interferon gamma receptor and increases its internalization and degradation. In addition, interferon beta-lb increases the suppressor activity of peripheral blood mononuclear cells.

No targeted studies have been conducted to determine the impact

interferon beta-lb on the function of the cardiovascular system, respiratory and

endocrine systems.

Clinical trial results

Relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis:

As part of a controlled clinical study of patients with relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis, capable of independent walking (EDSS from 0 to 5.5), who received interferon beta-lb, data were obtained that the drug reduces the frequency of exacerbations by 30%, reduces the severity exacerbations and the number of hospitalizations due to the underlying disease. Subsequently, an increase in the interval between exacerbations and a tendency to slow down the progression of relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis were shown.

Secondary progressive multiple sclerosis:

Two controlled clinical studies were conducted, including 1657 patients with secondary progressive multiple sclerosis. The studies involved patients with an initial EDSS value from 3 to 6.5 points, i.e. patients were able to walk independently. When assessing the primary endpoint of the study “time to confirmed progression”, i.e. ability to slow disease progression in studies, conflicting data have been obtained. One of the two studies showed a statistically significant slowdown in the rate of progression of disability (hazard ratio = 0.69 with 95% confidence interval (0.55, 0.86), p = 0.0010, risk reduction was 31% in the interferon beta-lb therapy group) and an increase in time to loss the ability to move independently, i.e. wheelchair use or EDSS 7.0 (hazard ratio = 0.61 with 95% confidence interval (0.44, 0.85), p = 0.0036, risk reduction was 39% in the interferon beta-lb group) among patients taking interferon beta-lb. The therapeutic effect of the drug persisted in the subsequent observation period, regardless of the frequency of exacerbations.

A second study of interferon beta-lb in patients with secondary progressive multiple sclerosis did not show a slowdown in the rate of progression. However, patients included in this study had less disease activity than patients in other studies of secondary progressive multiple sclerosis. A retrospective meta-analysis of data from both studies showed a statistically significant effect (p = 0.0076, when comparing groups of patients receiving interferon beta-lb 8 million IU and the placebo group).

Retrospective analysis by subgroups showed that the effect on the rate of progression was more pronounced in the group of patients with high disease activity before treatment (hazard ratio = 0.72 with 95% confidence interval (0.59, 0.88), p = 0.0011, risk reduction was 28% in the group patients with exacerbations or rapid progression of EDSS treated with interferon beta-lb compared with placebo). Based on the results of the analysis, it can be concluded that analysis of the frequency of relapses and rapid progression of EDSS (EDSS > 1 point or > 0.5 with a baseline EDSS > 6 points for the previous two years of therapy) can help identify patients with active disease. These studies also showed a reduction in exacerbation rates (30%). Interferon beta-lb has not been shown to have an effect on the duration of exacerbations.

Clinically isolated syndrome:

One controlled clinical trial of interferon beta-lb was conducted in patients with clinically isolated syndrome (CIS). CIS involves the presence of a single clinical episode of demyelination and/or at least two clinically silent lesions on T2-weighted MRI images, which are not sufficient to make a diagnosis of clinically definite MS. It has been established that CIS is highly likely to subsequently lead to the development of multiple sclerosis. Patients with one clinical lesion or two or more lesions on MRI were included in the study, provided that all alternative diseases that could be the most likely cause of the presenting symptoms other than multiple sclerosis were excluded.

This study consisted of two phases, a placebo-controlled phase and a follow-up phase. The placebo-controlled phase lasted 2 years or until the patient progressed to clinically definite multiple sclerosis (CDMS). After completion of the placebo-controlled phase, the patient entered the follow-up phase on interferon beta-lb therapy. To evaluate the early and delayed effects of interferon beta-lb, groups of patients initially randomized to interferon beta-lb (immediate treatment group) and placebo (delayed treatment group) were compared. During the study, patients and investigators remained blinded to treatment assignment.

Table 1. Efficacy of interferon beta-lb in the BENEFIT clinical trial and extended follow-up of BENEFIT trial patients.

| 2 year results | Year 3 results | Results based on 5- | |||||

| therapy | therapy | th year of observation | |||||

| Placebo | Subsequent phase | Subsequent phase | |||||

| controlled phase | open therapy | open therapy | |||||

| Interferon beta-lb 8 million IU | Placebo | Group immediately Wow treatment with interferon beta-lb 8 million ME n=292 | Delayed treatment group with interferon beta-lb 8 million IU | Interferon beta-lb immediate treatment group 8 million IU | Delayed treatment group with interferon beta-1 b 8 million IU | ||

| n=292 | n=176 | n=176 | n=292 | n=176 | |||

| Number | 271 (93%) | 166 | 249 | 143 (81%) | 235 (80%) | 123 (70%) | |

| patients | (94%) | (85%) | |||||

| completed | |||||||

| this phase | |||||||

| Key performance indicators | |||||||

| Time to development of clinically definite multiple sclerosis (CDMS) | |||||||

| According to Kaplan-Meier | 28% | 45% | 37% | 51% | 46% | 57% | |

| Risk Reduction | 47% compared to placebo | 41% compared with delayed interferon beta-1b treatment group | 37% compared with delayed interferon beta-1b treatment group | ||||

| hazard ratio at 95% CI | HR=0.53[0.39,0.73] | HR=0.59[0.42,0.83] | HR=0.63[0.48,0.83] | ||||

| Log rank test | pO.OOOl interferon beta-lb extended the time to onset of CDRS by 363 days, from 255 days in the placebo group (to 618 days in the interferon beta-lb group) | P=0.0011 | P=0.0027 | ||||

| Time to transformation into PC according to MacDonald criteria | |||||||

| According to Kaplan-Meier | 69% | 85% | Was not a primary endpoint | Was not a primary endpoint | |||

| Risk Reduction | 43% compared to placebo group | ||||||

| hazard ratio at 95% CI | HR=0.57[0.46,0.71] | ||||||

| Log rank test | p<0.000l | ||||||

| Time to EDSS progression | |||||||

| According to Kaplan- | Wasn't the main one | 16% | 24% | 25% | 29% | ||

| Mayer | end point | ||||||

| Decrease | 40% compared to | 24% compared to | |||||

| risk | interferon beta-1 b delayed treatment group | interferon beta-1 b delayed treatment group | |||||

| attitude | HR=0.60[0 | 39,0.92] | HR=0.76[0.52,1.11] | ||||

| risks at 95% CI | |||||||

| Log | P=0.022 | P=0.177 | |||||

| rank | |||||||

| test | |||||||

In the placebo-controlled phase of the study, interferon beta-lb statistically significantly prevented the transition of CIS to CDRS. In the group of patients receiving interferon beta-lb, a delay in transformation into definite multiple sclerosis according to the McDonald criteria was shown (see Table 1).

Subgroup analysis based on baseline factors demonstrated the effectiveness of interferon beta-lb in preventing transformation into CDRS in all subgroups. The risk of transformation to CDRS within 2 years was higher in the group of patients with monofocal CIS with 9 or more lesions on T2-weighted images or with the presence of contrast-enhancing lesions on MRI at baseline. The effectiveness of interferon beta-lb in the group of patients with multifocal clinical manifestations did not depend on the initial MRI parameters, which indicates a high risk of transformation of CIS into CDRS in patients in this group.

Currently, there is no generally accepted definition of high risk, but patients with monofocal CIS (clinical manifestation of 1 lesion in the central nervous system) and at least 9 lesions on T2-weighted MRI and/or accumulating contrast agent can be classified as high-risk for developing CDRS. Patients with multifocal CIS (clinical manifestations of >1 lesion in the central nervous system) are at high risk of developing CDRS, regardless of the number of lesions on MRI. In any case, the decision to prescribe interferon beta-lb should be made based on the conclusion that the patient is at high risk of developing CDRS.

Interferon beta-lb therapy was well tolerated by patients, as indicated by the low dropout rate (93% completed the study).

To improve tolerability, the dose of interferon beta-lb was titrated, and non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs were used at the beginning of therapy. In addition, an autoinjector was used in the majority of patients throughout the study.

Subsequently, interferon beta-lb remained highly effective in preventing the development of CDRS after 3 and 5 years of follow-up (Table 1), despite the fact that the majority of patients receiving placebo began therapy with interferon beta-lb two years after the start of the study. Confirmed EDSS progression (increase in EDSS at at least one visit compared with baseline) was lower in the immediate treatment group (Table 1, significant effect detected at 3 years of therapy, but no effect at 5 years). The majority of patients in both groups had no progression of disability over the 5-year period. There is no convincing evidence to support the effect of immediate administration of interferon beta-lb on this outcome. The effect of immediate treatment with interferon beta-lb on the quality of life of patients has not been shown.

Relapsing-remitting, secondary progressive multiple sclerosis and clinically isolated syndrome:

Interferon beta-lb has been shown to be effective in all clinical studies based on its ability to reduce disease activity (acute CNS inflammation and persistent tissue damage) as assessed by magnetic resonance imaging (MRI). The relationship between the clinical activity of multiple sclerosis and disease activity according to MRI indicators has not yet been fully established.