Tuberous sclerosis: about the disease and its treatment

Tuberous sclerosis (Bourneville disease) is a rare genetic disorder that can be inherited from a parent or occur as a result of a spontaneous genetic mutation.

One in 6,000 to 10,000 newborns has a mutation in one of the genes that causes this disease. 1 in 6–10 thousand people has a gene mutation that causes tuberous sclerosis.

The disease causes the occurrence of multiple benign tumors (hamartomas), which lead to disruption of the vital systems of the body.

The multisystem nature of tuberous sclerosis is expressed in damage to almost all organs - the brain, central nervous system, kidneys, heart, skin, retina, digestive tract, lungs, etc.

The manifestations of tuberous sclerosis that most affect quality of life are most often associated with its effects on the brain, and include epileptic seizures, developmental delays, including mental retardation, and autism. However, many patients are able to live full independent lives and be professionally in demand, working, for example, as doctors, lawyers, teachers and engineers.

Changes in the kidneys

Angiomyolipomas and cysts. Rarely - carcinomas. Kidney disorders usually appear in the 2nd - 3rd decade of life. Angiomyolipomas in tuberous sclerosis are multiple, bilateral and have an asymptomatic course for a long time.

Angiomyolipomas larger than 4 cm in diameter tend to hemorrhage spontaneously. The main clinical symptoms of hemorrhage from angiomyolipoma: acute abdominal pain, drop in blood pressure. Renal cysts in tuberous sclerosis are often small in size and bilateral. As the size of the cysts increases, kidney failure develops and high blood pressure appears.

Ultrasound. Kidney cysts

CT scan shows multiple bilateral formations in the kidneys containing adipose tissue – angiomyolipomas.

Symptoms

This disease is quite rare and therefore not fully studied. Its signs are varied, many organs and systems are affected, and therefore sometimes an accurate diagnosis can be made only after a comprehensive examination.

The signs of tuberous sclerosis are varied, many organs and systems are affected, and therefore sometimes an accurate diagnosis can be made only after a comprehensive examination.

Usually the first symptoms of the disease are polymorphic formations on the skin. Nodular tubercles with a diameter of 0.5 to 1 cm appear on different parts of the body (usually on the face - nose, cheeks, on the scalp in the scalp), as well as spots in the shape of “leaves”. Such depigmented areas of coffee-milky or whitish color on the skin can appear anywhere on the body. The probability of their appearance in newborns up to one year is 80%, in the second year – up to 100%. The number of areas with uneven depigmentation increases as the child grows older. In 15% of cases, both types of spots can occur - whitish and coffee-milky.

In addition to skin symptoms, signs of this type of sclerosis include: • myoclonic seizures, • tonic-clonic generalized seizures, • hemianopsia.

During myoclonic convulsions, the patient does not lose consciousness; individual muscle groups contract involuntarily and randomly. This pathological shock muscle twitching quickly passes. During generalized tonic-clonic seizures, a person suddenly loses consciousness. With massive spasm, involuntary separation of urine and trauma to the tongue may occur (the patient may bite it).

Hemianopsia is the partial loss of a person’s field of vision with limited space around.

Clinical manifestations

Typical symptoms:

- "White spots" of melanin hypopigmentation

- Facial angiofibromas: reddish nodules, initially the size of a grain of rice, later larger butterfly-shaped lesions on the cheeks, nasolabial folds and nose

- “Shagreen” plaques: skin lesions of various sizes with a “skiny” proliferation of connective tissue, which are localized mainly in the lumbosacral region

- Generalized convulsive seizures.

- Tuberous sclerosis in children has its symptoms from the first years of life - mental retardation, convulsive attacks in the form of myocloic seizures. The peak occurs during puberty. Then the disease acquires the symptoms indicated above.

Forms and causes of the disease. Prevention of the disease

There are two forms of tuberous sclerosis: - hereditary - spontaneous (de novo mutations)

Tuberous sclerosis is a hereditary disease. But even if the parents have a mutation in the genes, the birth of a healthy baby is quite likely. To do this, when planning a pregnancy, it is important to undergo a complete examination by a geneticist.

Bourneville disease is an autosomal dominant type. This is a type of inheritance in which a genetic disease manifests itself if a person has at least one mutated gene corresponding to it. The disease can be inherited from either parent with a 0-50% chance. Boys and girls get sick with the same frequency. The disease is not diagnosed immediately - either in infancy (up to 1 year) or in adolescence. Approximately one third of cases of tuberous sclerosis are due to heredity, the remaining two thirds are spontaneous, unpredictable genetic mutations.

Genes on chromosomes 9 and 16 are responsible for controlling the synthesis of hamartin and tuberin, proteins that suppress tumor processes. But when these genes are mutated, the barrier to the pathological growth of abnormal tissue disappears - and tumors form.

If the gene on chromosome 9 is damaged, tuberous sclerosis type I (TSC1) develops. With a mutation on chromosome 16, a diagnosis is made of TSC2 - type II of the disease.

But even if the parents have a mutation in the genes, the birth of a healthy baby is quite likely. Therefore, if there are hereditary diseases in the family, before planning a child, it is necessary to visit a geneticist for consultation and examination in order to exclude the possibility of the birth of a sick baby.

If tuberous sclerosis is suspected, it is necessary to consult a specialist (neurologist, dermatologist, geneticist, ophthalmologist, nephrologist, cardiologist, gastroenterologist, etc.) as soon as possible and undergo a comprehensive examination to reduce the risk of complications.

Changes in the visual organs

benign tumors of the retina and optic nerve (often multiple) - retinal hamartomas of astrocytic origin. It is observed in 50% of patients. The tumor is difficult to notice at the very beginning.

It calcifies quite quickly. Ophthalmic examination should be undertaken as early as possible in children with a dilated optic papilla. The tumor is often located near the optic disc.

Calcifications in retinal hamartomas on both sides.

Diagnostics and types of examination

When you first contact a doctor, you should tell about how long ago the first signs of the disease appeared, what kind of complaints are bothering you (convulsions, nodules on the tongue, skin, its depigmentation, partial blindness with the inability to see some part of the space), as well as whether there were any such illnesses in someone's family.

Mandatory examinations:

- General blood analysis

- General urine analysis

- Radiography

- Consultations with neurologists, ophthalmologists, dermatologists and geneticists

- MRI and CT

- EEG and ECG

- Echocardiography

- Ultrasound

General clinical tests - blood and urine - are required. If there is pathology in the blood test, the level of urea and creatinine may increase, since they are products of protein metabolism and indicate kidney function. If the kidneys are affected by the disease, blood may appear in the urine (hematuria).

Radiography is also prescribed to detect tumor growths in tissues.

At an appointment with a neurologist, you need to draw the doctor's attention to disturbing attacks of seizures, headaches, vomiting, changes in behavior and intellectual disorders.

Today it is impossible to undergo a comprehensive examination without tomography - magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) and computer computed tomography (CT). Thanks to their use, specialists can: • engage closely in a layer-by-layer study of the structure of the brain; • identify tumors in it (they are more often found at the border of gray matter with white matter); • detect signs of abnormal development of brain matter and areas with reduced density of its nervous tissue; • identify accumulations of cerebrospinal fluid (cerebrospinal fluid that supplies the brain with nutrition and metabolic processes) in the cavities of the brain.

Using electroencephalography (EEG), specialists assess brain activity in different areas. This method of examination makes it possible to search for foci with increased impulses that provoke convulsive attacks in tuberous sclerosis.

To determine whether there are growths in the heart muscle (rhabdomyomas), the patient is sent for echocardiography.

Electrocardiography (ECG) is recommended for all patients because Cardiac arrhythmia, although rare, can lead to sudden death. Ultrasound (ultrasound) will help check for the presence of kidney tumors and cysts in their tissue.

The ophthalmologist will conduct a series of examinations: • using a slit lamp (biomicroscopy) to examine the fundus of the eye; • using tables to check visual acuity (visometry); • perimetry to determine the edge of the visual field to identify defects in it; • assessment of the condition of the retina, the fundus of the eye and its vessels, the disc (nipple) of the optic nerve (ophthalmoscopy) to determine the presence of pathological changes (swelling of the nipple, retinal hamartomas).

At your appointment, the dermatologist will definitely pay attention to the presence of formations on the skin in the form of reddish nodules around the nails, tubercles, growths, fibrous plaques and areas with insufficient pigmentation.

A comprehensive examination cannot be done without the help of a geneticist, who will prescribe a special test to identify mutational changes in the genes of the 9th and 16th chromosomes (TSC1, TSC2). If necessary, a consultation with a neurosurgeon or psychiatrist is prescribed.

Bourneville–Pringle disease

Bourneville-Pringle disease (tuberous sclerosis) is a heterogeneous, genetically determined disease characterized by hyperplasia of ecto- and mesoderm derivatives, damage to the skin, nervous system and the presence of benign tumors (hamartomas) in various organs. In 1880, a description of the disease was published by D. M. Bourneville and in 1890 by J. J. Pringle.

Bourneville-Pringle disease is inherited in an autosomal dominant manner and is characterized by variable expressivity and incomplete penetrance. The development of the disease is determined by linkage to loci 9q34 (type 1 - TSC1), Ilql4-llq23 and 16p13.3 (type 2 - TSC2). There is evidence of a gene mutation on chromosome 12. Hamartin (encoded by TSC1) is proposed to be a tumor suppressor protein, and tuberin (encoded by TSC2) regulates endocytosis. There may be a defect in the DNA repair system, as evidenced by the increased sensitivity of cells to ionizing radiation. In 50–75% of cases, the disease may be caused by new mutations. The incidence of Bourneville-Pringle disease is 1:30,000 in the population. Prevalence among newborns varies up to 5–7 cases per 100,000 births [1, 2].

In angiofibromas, growth of connective tissue, proliferation of small vessels, mainly of the capillary type, and expansion of their lumens are observed. Connective tissue nevi in Bourneville–Pringle disease are represented by collagenomas. The epithelium is usually without features, but can be changed like an epidermal nevus. The dermis is thickened due to hypertrophied collagen fibers [1].

Clinical symptoms of Bourneville-Pringle disease appear in the first years of life, but can exist from birth. The process gradually progresses, especially during puberty. The skin is affected in 96% of cases [3]. Skin manifestations of Bourneville-Pringle disease are represented by angiofibromas and fibromatous lesions on the face, periungual fibromas, shagreen plaques, hypomelanotic spots, and café-au-lait pigment spots. In 1998, diagnostic criteria for the disease were adopted (Table) [4].

According to the above diagnostic criteria, an undoubted diagnosis of Bourneville-Pringle disease is made in the case of two or one primary sign and two secondary signs. Possible diagnosis: one primary symptom and one secondary symptom. Presumptive diagnosis: either one primary sign, or two (or more) secondary signs (table).

Hypopigmented skin patches exist from birth or appear during infancy and are one of the most common cutaneous manifestations of Bourneville-Pringle disease. In the first year of life they are found in 80% of patients, in the second year - in 100% [3, 5]. With age, there is a tendency for their number to increase. Hypopigment spots in this disease are localized mainly on the trunk and buttocks. Their characteristic feature is their asymmetry of location. Variability in the number, size and shape of spots was noted. The most characteristic of them have the outline of a leaf, pointed on one side and rounded on the other, pale grayish or milky white in color. On light skin they are visible only with a Wood's lamp. Over time, the spots may slowly repigment. Only multiple elements have diagnostic significance, especially when combined with epileptiform seizures. From infancy, white strands of hair, eyelashes and eyebrows can be detected, which, like hypopigmented spots, are a characteristic sign of Bourneville-Pringle disease.

Along with hypopigment spots in Bourneville-Pringle disease, in 15.4% of cases there are café-au-lait pigment spots, which do not differ from those in healthy individuals, but their presence in combination with other symptoms helps in making a diagnosis.

In 47–90% of cases, angiofibromas are observed, which are an obligate sign of Bourneville-Pringle disease. Angiofibromas appear in only 20% of patients in the first year of life, and in 50% by the age of three; they are usually located symmetrically on the wings of the nose, in the nasolabial folds and on the chin. They are small hemispherical dense tumor-like elements, 1–5 mm in size, flesh-colored, yellowish-red or reddish-brown. Their surface is shiny, smooth, but can be verrucous, covered with telangiectasia (Fig. 1, 2).

In the area of the skin of the forehead, scalp, and cheeks, large tumor-like fibromatous foci observed are also an obligate sign of the disease and occur in 25% of patients with Bourneville-Pringle disease. Fibromatous lesions can be either single or multiple, have a variable color - from the color of normal skin to light brown, protrude somewhat above the surrounding skin, and have a soft or dense consistency. They often appear already in the first year of life and are one of the first clinical symptoms of the disease. Fibrous plaques are most often localized on the forehead. Their sizes and number may vary. Soft fibromas occur in 30% of patients; they are multiple or single soft formations on legs, saccular in shape, growing on the neck, trunk and limbs. Another variant of soft fibromas are multiple, slightly raised above the surface of the skin (and of the same color) small formations, less than 0.3 cm in diameter, located on the torso and neck and resembling goose bumps.

Subungual and periungual fibromas (Koenen tumors) and hypertrophic changes in the gums are common. Periungual fibromas, an obligate feature of Bourneville-Pringle disease, are dull, red or meat-colored papules or nodules growing from the nail bed or around the nail plate. Koenen's tumor appears in late childhood and occurs in 17–52% of cases. In most cases, periungual fibromas appear in the second decade of life. Most often they are localized on the legs. Their size varies from 1 mm to 1 cm in diameter. Histologically, Koenen's tumor is an angiofibroma.

Shagreen plaques, or “shagreen skin,” develop in the first decade of life in approximately 40% of patients and are connective tissue nevi. In most cases, “shagreen skin” appears in the second decade of life. Shagreen-like plaques can be either single or multiple, from small in size to 10 or more cm in diameter, with a porous surface like a “lemon peel”. Areas of “shagreen skin” are observed mainly in the lumbosacral region, have the appearance of flat, slightly raised lesions, located mainly in the lumbosacral region, the color of normal skin or weakly pigmented.

In Bourneville-Pringle disease, various systemic changes in the body occur. Neurological symptoms may be the very first signs of illness, suddenly appearing against the background of external health and well-being in a child without noticeable dysplasia or developmental disorders. They appear at the age of 3–4 months in the form of convulsive attacks. Lesions of the nervous system are dominant in the clinical picture of Bourneville-Pringle disease. The most common symptoms are convulsive paroxysms, mental retardation, behavioral disorders, and changes in the sleep-wake cycle.

Convulsive paroxysms, one of the most significant symptoms of Bourneville-Pringle disease, are observed in 80–92% of patients [6] and are most often a manifest symptom of the disease. The first attacks are general tonic, then they become polymorphic (general, focal, large, small, nodding, rolling eyes, freezing, convulsions). Frequent seizures are generally observed until the age of 6–7 years, and then they may subside. In some patients, attacks continue into older age. In some, they have a severe course, and status epilepticus can develop with a fatal outcome [7]. The earlier epilepsy begins, the more severe the mental retardation [3]. Epileptic paroxysms in Bourneville-Pringle disease are often resistant to anticonvulsant therapy, can lead to the development of intellectual and behavioral disorders, and are one of the main causes of disability in children with Bourneville-Pringle disease. Among the factors that determine resistance to anticonvulsant therapy, the most important are: onset before the age of one year, the presence of several types of seizures, high frequency of seizures, changes in the nature of seizures over the course of the disease [8].

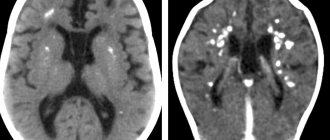

The most common brain lesions in Bourneville-Pringle disease are cortical tubera, subependymal ganglia, and white matter abnormalities. Tuberal calcification is observed in 54% of cases and increases with the age of patients. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is of great importance in the verification of tubers when examining patients with Bourneville-Pringle disease, which allows visualization of tubers in 95% of cases.

Subependymal nodes occur in 95% of cases and are detected by both computed tomography (CT) and MRI studies of the brain. Subependymal nodes are in most cases multiple, adjacent to each other. They are localized, as a rule, in the walls of the lateral ventricles, less often in the walls of the third and fourth ventricles of the brain. Subependymal nodes often transform into giant cell astrocytoma and are detected in 10–15% of patients [5]. Subependymal giant cell astrocytomas usually manifest between the 5th and 10th years of life (the average age at the time of tumor detection is 13 years), usually tend to grow and are always localized at the interventricular foramen. In 10% of patients with Bourneville–Pringle disease, cerebellar lesions are described.

Among the more rare neurological symptoms are central spastic paralysis, pyramidal and extrapyramidal symptoms, and when the tumor grows into the ventricular cavity - internal hydrocephalus. Congestive papillae of the optic nerves, their atrophy, and in rare cases, endocrine disorders in the form of adrenogenital syndrome and disorders of the cranial nerves can be detected. In rare cases, spongioblastomas developing from the focus of Bourneville-Pringle disease are observed, with corresponding tumor symptoms.

The development of mental retardation is noticed later than the onset of convulsive syndrome and is recorded in approximately 49% of patients; it gradually worsens due to the destruction of the brain affected by Bourneville-Pringle disease, and can reach the level of deep imbecility. Mental development lags behind, motor skills are destroyed, and speech is impaired. By puberty, intellectual impairment can reach the level of idiocy. D. M. Bourneville (1880) published a description of this disease under the title “contribution to the study of idiocy.” However, with a mildly expressed destructive process, the clinical manifestations are not so severe, the evolutionary dynamics of the development of the nervous system to a certain extent overlaps the pathological process, and these children are brought to a psychiatrist with oligophrenic intellectual underdevelopment [3, 7].

An intellectual defect can sharply deepen with the development of psychotic disorders. Schizophrenia-like psychoses with fears, persecution mania, behavioral abnormalities with psychopathic traits, personality changes of a limited type with viscosity, uncriticality, and importunity are observed. Even with mild forms of dementia, when the defect grows slowly over years, we have to remember that this disease has a progressive course and, therefore, an unfavorable prognosis. However, 30% of patients do not have dementia. But the statistics are not accurate, since they provide data on the registration of patients who applied.

Often, when the eyes are affected, congestive nipples and sometimes atrophy of the optic nerves are detected. During an ophthalmoscopic examination, more than 50% of patients have a pathognomonic picture of retinal phacoma. These nevoid formations come in three types. In the first, most common variant, hamartomas have a delicate, relatively flat and smooth surface, orange-pink color, round or oval shape, and are localized mainly in the superficial layers of the retina. In the second case, the hamartomas have a nodular appearance and resemble a mulberry. They are white, calcified, and opaque. In the third option, hamartomas combine the features of the first two. They are round in shape with a nodular and calcified center and a translucent, smooth orange-pink periphery. Such manifestations have important diagnostic value due to their characteristic appearance. In some patients, this may be one of the only manifestations of Bourneville-Pringle disease. Other changes in the organ of vision are recorded much less frequently: chorioretinitis, zones of depigmentation, congenital cataracts, congenital blindness. There are also connective tissue nodules on the conjunctiva. Clinical manifestations of hamartomas are extremely rare. The main symptom is a progressive decrease in vision [2, 7].

Tumors in the internal organs do not cause clinical symptoms in many patients, but are often detected at autopsy, especially kidney tumors. It is believed that kidney tumors are detected in 40–50% of patients. These are multiple bilateral small hamartomas of connective tissue fibers, adipose tissue, and epithelium. Sometimes large kidney tumors occur.

Changes in the cardiovascular system in Bourneville-Pringle disease are manifested by the development of rhabdomyomas, which often serve as the first clinical sign of Bourneville-Pringle disease along with hypopigmented spots. In 1863, Recklinghausen described a combination of brain damage with rhabdomyoma. Rhabdomyomas occur in 30–60% of cases and are detected more often in males (ratio 2:1). The highest incidence of cardiac rhabdomyoma in Bourneville-Pringle disease is observed in newborns and infants. Cardiac rhabdomyomas, as a rule, increase rapidly during the second half of pregnancy, generally reaching maximum values at the time of birth, and then gradually decrease in size. Most rhabdomyomas disappear without a trace. Spontaneous regression of rhabdomyomas can occur in children under six years of age. After six years, tumors usually do not disappear, but may decrease slightly in size. Regression of tumors can be observed both in size and in number [5].

Lung lesions in the form of fibrous tumors, fibroleiomyomas, cystic formations, and interstitial fibrosis are also not very uncommon. Patients experience attacks of dyspnea, recurrent spontaneous pneumothorax, hemoptysis, and pulmonary failure. Tumors of the pancreas, liver, bladder, gastrointestinal tract and other organs are described. Fibromas of the gums, tongue, pharynx, and larynx are found on the mucous membranes [7].

Differential diagnosis of hypopigmented spots in Bourneville-Pringle disease should be carried out with a focal form of vitiligo, anemic nevus, pityriasis versicolor, apigmented nevus, post-inflammatory hypopigmentation. Angiofibroma should be differentiated from tricholemmoma, syringoma, and intradermal noncellular nevus. Koenen's tumor should be differentiated from simple warts [3].

When diagnosing skin lesions, additional paraclinical studies are not required if the patient presents with pseudoadenomas and other typical clearly visible lesions. They are so pathognomonic that there is usually no need to resort to pathological examination as part of routine diagnosis. But at the same time, knowing about the wide range of manifestations of Bourneville-Pringle disease, one cannot stop only at the level of dermatological diagnosis. The patient must be referred to a psychiatrist, neurologist, ophthalmologist, therapist, or surgeon. It is necessary to do an electrocardiogram, x-ray of the chest, skull, hands and feet, electroencephalography, CT, MRI, urinalysis (hematuria with kidney damage). There may be a need to examine the skin with a Wood's lamp if relatives of patients suspect mild manifestations of unclear white spots. A pathomorphological examination of white spots can also be done if the skin symptoms are represented only by achromic lesions. It is also advisable to use a Wood's lamp when examining children born from parents with Bourneville-Pringle disease. This study is especially important at an age when typical pseudoadenomas are still absent (up to 3–5 years). In severe forms of the disease, 30% of patients do not survive beyond 5 years; 50–75% die in childhood and adolescence. Malignant gliomas are not uncommon. Medical genetic counseling should be performed [3].

The prognosis for recovery is unfavorable. With severe systemic changes, mortality is high in childhood and young adults from status epilepticus, cardiac, renal or pulmonary failure. The severity of skin changes does not affect the risk of involvement of internal organs in the process.

During treatment, the largest elements are removed by electrocoagulation, cryodestruction, and laser radiation. There is a decrease in the size of angiofibromas with Tigazon (1 mg per kg of body weight) [1]. Dermabrasion may be useful and should be carried out after the process has stabilized. Anticonvulsant drugs (Difenin, etc.) are prescribed for a long time, and drugs that reduce intracranial pressure and normalize heart rhythm in cardiac rhabdomyoma are periodically prescribed. The treatment of choice for brain tumors is surgical removal. For the purpose of prenatal diagnosis, echocardiography can be used to detect cardiac rhabdomyoma in the fetus.

Literature

- Mordovtsev V.N., Mordovtseva V.V., Mordovtseva V.V. Hereditary diseases and malformations of the skin. Atlas. M.: Nauka, 2004. pp. 40–42.

- Strakhova O. S., Katysheva O. V., Dorofeeva M. Yu., Perminov V. S., Pivovarova A. M., Osipova E. K., Dobrynina M. V., Chumak O. I. Tuberous sclerosis / / Russian medical journal. 2004. No. 3. P. 52–54.

- Fitzpatrick T., Johnson R., Wolfe K., Polano M., Surmond D. Dermatology: a reference atlas. 1999. pp. 460–466.

- Roach ES, DiMario FJ, Kandt RS, Northrup H. Tuberous Sclerosis Consensus Conference: Recommendations for Diagnostic Evaluation // Journal of Child Neurology. 1999. V. 14. R. 401–407.

- Dorofeeva M. Yu. Tuberous sclerosis in children // Russian Bulletin of Perinatology and Pediatrics. 2001. No. 4. P. 33–41.

- Curatolo P., Seri S. Seizures. In: Nuberous Sclerosis complex: from Basic Science to Clinical Phenotypes. Ed: Curatolo P. London, England: Mac Keith Press. 2003. R. 46–77.

- Suvorova K. N., Kuklin V. T., Rukavishnikova V. M. Pediatric dermatovenerology. Kazan, 1996. pp. 50–56.

- Curatolo P. Tuberous Sclerosis. In: Infantile Spasms and West Syndrome. Ed. by O. Dulac, H. T. Chugani, B. Dalla Bernandina. WB Saunders. Company Ltd, London, Philadelphia, Toronto, Sydney, Tokio. 1994, pp. 192–202.

L. A. Yusupova, Doctor of Medical Sciences Z. Sh. Garayeva, Candidate of Medical Sciences, Associate Professor E. I. Yunusova, Candidate of Medical Sciences, Associate Professor G. I. Mavlyutova, Candidate of Medical Sciences L. A. Khaertdinova, Candidate of Medical Sciences, Associate Professor E. E. Galikhanova, Candidate of Medical Sciences V. N. Rokitskaya, Candidate of Medical Sciences, Associate Professor

GBOU DPO KSMA Ministry of Health and Social Development of Russia, Kazan

Contact information for authors for correspondence

Changes in the nervous system

seizures, mental retardation, behavioral disorders, changes in the sleep-wake cycle. Seizures in tuberous sclerosis can begin in the first year of life. Most often during this age period, infantile spasms occur, which later develop into other types of seizures. Seizures in tuberous sclerosis often respond poorly to anticonvulsant therapy. Mental retardation in tuberous sclerosis is observed in half of the patients. The degree of reduction in mental retardation ranges from moderate to severe. Behavioral changes are characterized by autism, hypermobility and attention deficit disorder, aggression and self-aggression. Sleep disturbances in most patients are associated with prolonged falling asleep, sleepwalking and early awakening.

The most typical abnormalities in the brain are the cortical tubers and subependymal nodes. Tubers can be either single or multiple; they are located in the form of protrusions above a single or adjacent grooves of the cortex, expanding them. Subependymal nodes are localized in the walls of the lateral ventricles and, less commonly, in the walls of the third and fourth ventricles of the brain. In newborns, subependymal nodes are rarely calcified. As the child grows, there is a gradual deposition of calcium in the subependymal nodes.

Subependymal nodes in 10% of cases transform into giant cell astrocytoma, which usually manifest between 5 and 10 years of life, tend to grow and are localized at the foramen of Monroe

Subependymal calcifications and cortical tubers on a CT scan of the brain of a child with tuberous sclerosis

Subepindeminal nodes and cortical tubercles on MRI

Astrocytoma in the area of the foramina often leads to occlusive hydrocephalus.