general information

Epilepsy attacks have been known to people for a very long time. It was either mistaken for demonic possession or associated with a person’s special talent. Today, one or another form of pathology is observed in 10 people out of 1000. Symptoms can occur in newborns and the elderly, in men and women with the same frequency. Moreover, similar processes occur in the central nervous system of some animals, for example, dogs.

The main mechanism for the occurrence of attacks is the synchronization of the work of all nerve cells in a certain area. It is called an epileptogenic focus and determines the set of symptoms and their severity. Contrary to popular belief, the disease is not limited to seizures with loss of consciousness. There are a large number of variants of seizures with varied symptoms, depending on the area of the brain in which the pathological focus occurs.

Make an appointment

What is focal epilepsy

Symptomatic focal epilepsy is one of the forms of the disease in which seizures are explained by the presence in the brain of a clear and distinct focus of paroxysmal activity. As a rule, the pathology is characterized by secondary manifestations or develops against the background of other serious diseases. It is determined by simple and complex manifestations of seizures, based on the main characteristics of which the lesion can be determined.

Focal epilepsy combines any types of seizures, the formation and manifestation of which directly depends on the zone of electrical activity of neurons in cerebral structures. Starting from a small focus, epileptic activity can subsequently spread, covering an increasingly larger area of the cerebral cortex, while stimulating the development of secondary generalized seizures.

Multifocal epilepsy, caused by the presence of several lesions at once, is especially dangerous for the patient. Features of the pathology:

- if all forms of the disease are taken into account, FE accounts for more than 82% of cases;

- in more than 75% of cases, the first attack can be noticed in childhood;

- Pathology especially often develops against the background of brain damage of any etiology: infectious, traumatic, ischemic, as well as as a result of developmental anomalies as a consequence of disorders of the prenatal and birth periods;

- symptomatic focal epilepsy (ICD code 10 G40) occurs in more than 71% of cases.

Causes

The functioning of the brain is a complex process that requires the constant interaction of many structures. A failure at any level can cause the formation of an epileptogenic focus. Among the most common causes of epilepsy in adults and children are:

- heredity;

- traumatic brain injuries;

- acute or chronic intoxication, especially alcoholism;

- infectious lesions of the brain or its membranes (encephalitis, meningitis);

- acute and chronic cerebrovascular accidents, including strokes;

- malignant and benign tumors in the cranial cavity;

- birth injuries;

- parasites that develop in brain structures: echinococcus, pork tapeworm;

- neurodegenerative diseases (Alzheimer's disease, multiple sclerosis, Pick's disease);

- hormonal imbalances, especially lack of testosterone;

- metabolic disorders, etc.

There are cases when the cause of epilepsy cannot be identified. In this case, the disease is called idiopathic.

Types and symptoms

Epilepsy is multifaceted and multifaceted; its symptoms are not limited to seizures. The most common classification is depending on the severity of attacks and their main manifestations.

Aura (harbingers)

Many epileptic seizures begin with an aura. This is the name given to a complex of specific sensations that occurs shortly before a seizure. Manifestations of an aura can be completely different: paresthesia (pathological sensations), a specific taste in the mouth, auditory, visual or olfactory hallucinations, etc. Before the appearance of an aura, a person often begins to experience causeless anxiety and internal tension.

Partial (focal) seizures

These conditions occur when a small area of the brain is involved in pathological overexcitation.

Simple partial seizures are characterized by preserved consciousness and last only 1-2 minutes. Depending on the location of the pathological focus, a person feels:

- sudden change of mood for no apparent reason;

- small twitching in a certain part of the body;

- feeling of déjà vu;

- hallucinations: lights before the eyes, strange sounds, etc.;

- paresthesia: a feeling of tingling or crawling in any part of the body;

- difficulty pronouncing or understanding words;

- nausea;

- change in heart rate, etc.

Complex attacks are characterized by more severe symptoms and often affect consciousness and thinking. Human can:

- lose consciousness for 1-2 minutes;

- there is no point in looking into emptiness;

- scream, cry, laugh for no apparent reason;

- constantly repeat any words or actions (chewing, walking in a circle, etc.).

Typically, during a complex seizure and for some time after it, the patient remains disoriented for some time.

Generalized seizures

Generalized seizures are one of the classic signs of epilepsy that almost everyone has heard of. They occur if the epileptogenic focus has spread to the entire brain. There are several forms of seizures.

- Tonic convulsions. The muscles of most of the body (especially the back and limbs) simultaneously contract (come to tone), remain in this state for 10-20 seconds and then relax. Such attacks often occur during sleep and are not accompanied by loss of consciousness.

- Clonic convulsions. Rarely occur in isolation from other types of attacks. Manifested by rhythmic rapid contraction and relaxation of muscles. The movement cannot be stopped or delayed.

- Tonic-clonic seizures. This type of attack is called grand mal, which means “great illness” in French. The attack is divided into several phases: precursors (aura);

- tonic convulsions (20-60 seconds): the muscles become very tense, the person screams and falls; at this time his breathing stops, his face becomes bluish, and his body arches;

- clonic convulsions (2-5 minutes): the muscles of the body begin to contract rhythmically, the person thrashes on the floor, foam is released from the mouth, often mixed with blood due to a bitten tongue;

- relaxation: convulsions stop, muscles relax, involuntary urination or defecation often occurs; consciousness is absent for 15-30 minutes.

After the end of a generalized seizure, a person remains for 1-2 days feeling overwhelmed, problems with coordination of movements and fine motor skills. They are associated with cerebral hypoxia.

- Atonic attacks. They are characterized by short-term muscle relaxation, accompanied by loss of consciousness and falling. The attack lasts literally 10-15 seconds, but after it ends the patient does not remember anything.

- Myoclonic seizures. They manifest themselves as rapid twitching of the muscles of individual parts of the body, usually the arms or legs. The seizure is not accompanied by loss of consciousness.

- Absence seizures. The second name for attacks is petit mal (minor illness). This symptom of epilepsy occurs more often in children than in adults and is characterized by a short-term loss of consciousness. The patient freezes in place, looks into emptiness, does not perceive speech addressed to him and does not react to it. The condition is often accompanied by involuntary blinking of the eyes, small movements of the hands or jaws. The duration of the attack is 10-20 seconds.

Pediatric epilepsy

Childhood epilepsy has many masks. In newborns, it can be manifested by periodic muscle contractions that do not resemble seizures, frequent tilting of the head back, poor sleep and general restlessness. Older children may suffer from classic seizures and absence seizures. Partial seizures most often occur:

- severe headaches, nausea, vomiting;

- short periods of speech disorder (the child cannot utter a single word);

- nightmares followed by screams and hysterics;

- sleepwalking, etc.

These symptoms are not always a sign of epilepsy, but they should serve as a reason for an urgent visit to the doctor and a full examination.

Parietal epilepsy, seizures

In two thirds of cases, patients suffer from somatosensory attacks: paresthesia, dysesthesia, painful sensations (burning, numbness or tingling) that spread to the face and hands.

Somatic illusions accompany parietal epilepsy slightly less frequently than somatosensory seizures.

A person feels an “incorrectness” in posture, movements or position of the limbs, or less often, he does not feel the limbs or the whole body at all. Similar illusions occur if the non-dominant hemisphere is affected.

Cases of sensations in the genitals and orgasm are described. If the dominant hemisphere is affected, linguistic difficulties occur - alexia with dyscalculia and agraphia. In case of damage to the non-dominant hemisphere of the brain, orientation in space is disrupted.

Simple focal sensory seizures can spread to extraparietal areas and cause unilateral focal cloning (in more than half of patients), eye and head version (40%), tonic settings of any limb (about 30%) and automatisms (about 20%) .

Most patients experience tonic-clonic seizures of a secondary generalized nature.

Diagnostics

Neurologists diagnose and treat epilepsy. Some of them specifically expand their qualifications in this area, which allows them to act even more effectively.

Examination of a patient with suspected epilepsy includes the following methods:

- collection of complaints and medical history: the doctor asks the patient in detail about the symptoms that bother him, finds out the time and circumstances of their occurrence; a characteristic sign of epilepsy is the appearance of seizures against the background of sharp sounds, bright or flashing lights, etc.; special attention is paid to heredity, past injuries and diseases, the patient’s lifestyle and bad habits;

- neurological examination: the doctor evaluates muscle strength, skin sensitivity, severity and symmetrical reflexes;

- EEG (electroencephalography): a procedure for recording the electrical activity of the brain, allowing one to see the characteristic activity of an epileptogenic focus; if necessary, the doctor may try to provoke overexcitation using flashes of light or rhythmic sounds;

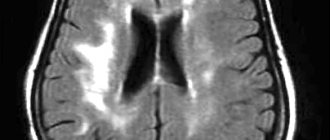

- MRI of the brain: makes it possible to identify pathological areas and formations: tumors, fissures, ischemic areas, consequences of a stroke, etc.;

- angiography of the vessels of the head: injection of a contrast agent into the blood followed by radiography; allows you to see areas of vasoconstriction and deterioration of blood flow;

- Ultrasound of the brain (Echo-encephalogram): used in children of the first year of life whose fontanel has not yet closed; visualizes tumors and other space-occupying formations, fluid accumulation, etc.;

- rheoencephalography: measurement of electrical resistance of head tissue, which can be used to diagnose blood flow disorders;

- general examinations: general blood and urine tests, blood biochemistry, tests for infections, ECG, etc. for a comprehensive assessment of the patient’s condition;

- consultations with specialized specialists: neurosurgeon, toxicologist, narcologist, psychiatrist, etc. (prescribed depending on the suspected cause of the attacks).

The list of studies may vary depending on the patient’s age, type of attack, presence of chronic pathologies and other factors.

Localization-related forms of epilepsy in children and their treatment

Epilepsy is the most common serious paroxysmal disorder of cerebral function, with a prevalence in the general population ranging from 0.3% to 2% [1]. Epilepsy is a group of chronic paroxysmal diseases of the brain, manifested by repeated convulsive or non-convulsive stereotypical seizures, accompanied by a variety of personality changes and a decrease in cognitive functions [2–5].

Types of epilepsy are currently considered in accordance with the classification adopted in 1981. Based on the type of seizures present, they are distinguished: I. Partial (focal) seizures: a) simple partial; b) complex partials; c) partial with secondary generalization; II. Generalized seizures: a) absences (typical, atypical): b) myoclonic seizures; c) clonic seizures; d) tonic seizures; e) tonic-clonic seizures; f) atonic seizures; III. Unclassified epileptic seizures [1].

In the classification of epilepsies, epileptic syndromes and similar diseases, adopted by the International League Against Epilepsy (1989), the following headings are distinguished:

I. Localization-related forms (focal, focal, local, partial):

- idiopathic (with age-dependent onset): benign epilepsy of childhood with central temporal peaks (rolandic); childhood epilepsy with occipital paroxysms; primary reading epilepsy;

- symptomatic: chronic progressive partial epilepsy of Kozhevnikov; attacks characterized by specific methods of provocation; other forms of epilepsy with a known etiology or organic changes in the brain (frontal, temporal, parietal, occipital);

- cryptogenic.

II. Generalized forms of epilepsy:

- idiopathic (with age-dependent onset): benign familial seizures of newborns; benign neonatal seizures; benign myoclonic epilepsy of infancy; childhood absence epilepsy (pycnolepsy); juvenile absence epilepsy; juvenile myoclonic epilepsy; epilepsy with generalized convulsive seizures of awakening; other idiopathic generalized forms of epilepsy not mentioned above; forms characterized by specific methods of provocation (more often photosensitivity epilepsy);

- cryptogenic and/or symptomatic: West syndrome (infantile spasms); Lennox–Gastaut syndrome; epilepsy with myoclonic-astatic seizures; epilepsy with myoclonic absence seizures;

- symptomatic: 2.3.1. nonspecific etiology: early myoclonic encephalopathy; early infantile epileptic encephalopathy with a burst-suppression pattern on the EEG (Otahara syndrome); other symptomatic generalized forms of epilepsy not mentioned above; 2.3.2. specific syndromes.

III. Epilepsies that do not have a clear classification as partial or generalized:

- having both generalized and partial manifestations: neonatal convulsions; severe myoclonic epilepsy of early childhood; epilepsy with continuous peak waves during slow-wave sleep; Landau–Kleffner acquired epileptic aphasia; other unclassified forms of epilepsy not defined above;

- attacks that do not have clear generalized or partial signs.

IV. Specific syndromes:

- situationally determined attacks: febrile convulsions; attacks that occur only due to acute metabolic or toxic disorders;

- isolated seizures or isolated status epilepticus [1].

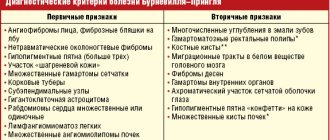

Clinical manifestations depend on the form of epilepsy and the types of seizures. Diagnosis is based on a careful collection of anamnesis, characteristics of attacks (duration, frequency, time of occurrence, presence of aura, changes in consciousness, skin color, postictal weakness, etc.), assessment of neurological status (including identification of congenital defects of the visual organs and other anomalies, dysmorphic habitus, skin changes, etc.).

Instrumental and laboratory studies for epilepsy include: electroencephalography (EEG) and/or video-EEG monitoring, neuroimaging methods - computed tomography (CT) and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the brain, radiographic examination of the skull (in the absence of CT and MRI) , ECG study (to exclude the cardiogenic origin of paroxysms), biochemical blood test (Ca, glucose, lactate, pyruvate, carnitine, etc.), analysis of amino acids in the blood and cerebrospinal fluid (CSF), study of chromosomal karyotype, DNA analysis for the presence of fragile chromosomes, etc. [1–7].

Antiepileptic drugs (AEDs) used in the Russian Federation are relatively numerous. Among the 1st generation AEDs are phenobarbital, benzobarbital, primidone, phenytoin, clonazepam, ethosuximide, valproate and carbamazepine, and among the new AEDs (2nd generation) are topiramate, lamotrigine, levetiracetam, oxcarbazepine, gabapentin, zonisamide, etc. In addition listed AEDs, the following drugs can be used in various clinical situations: acetazolamide, midazolam, diazepam, etc. [8].

Alternative methods of drug therapy for epilepsy include the use of human immunoglobulins for intravenous administration, a synthetic analogue of adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH) and the neuropeptide drug Cortexin for some forms of the disease [9]. Among the non-drug methods of treating epilepsy, psychotherapy and a biofeedback system are used according to indications; neurosurgical interventions (hemispherectomy, anterior temporal lobectomy, limited temporal resection, extratemporal neocortical resection); stimulation of the vagus nerve with implantable devices, neuronutrition methods [9, 10].

Among the latter are ketogenic diets (KD): classical (according to Wilder RM et al.), liberalized (according to Huttenlocher PR et al. - based on medium chain triglycerides), KD based on long chain triglycerides, KD based on corn oil (according to Woody RC et al. .), “John Radcliff”, “The Great Ormond Street”, etc. [10]. KDs simulate a state of starvation in the body, forcing it to use more fat as energy sources, leading to the production of ketone bodies. Hartman AL et al. (2007) among the neuropharmacological factors of KD, they highlight the effect on the gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABA) system and neurosteroids; excitotor amino acid systems and ionotropic glutamate receptors; effects on ion channels and proteins associated with synaptic transmission; influence on energy metabolism; changes in brain pH, etc. [11]. Other neurodietological methods are also used: the Atkins diet, oligoantigen diet, vitamin therapy, the use of food additives and other nutrients (lecithin, essential fatty acids - omega-3, carnitine, taurine, dimethylglycine, Mg, Mn), etc. [12].

Epilepsies with a possible onset at any age include symptomatic and probably symptomatic focal epilepsies, among which temporal (medial and lateral), frontal, parietal and occipital forms are distinguished (depending on the location of the epileptogenic focus) [2, 6, 7, 13] . They deserve special attention in pediatric neurology.

Frontal epilepsy. This disease with a high frequency and relatively short duration of attacks is characterized by pronounced diversity:

- seizures originating from the motor cortex (simple focal, often with secondary generalization and postictal paralysis);

- seizures emanating from the supplementary motor cortex (sudden tension of a limb or limbs with vocalisms, tonic adduction of arms and legs, stoppage of speech, secondary generalization);

- opercular seizures (“chewing”, hypersalivation, autonomic disorders, speech arrest, simple partial seizures);

- anterior frontopolar paroxysms (head adversion at the beginning of the attack, contact disturbances, axial clonic convulsions, violent thoughts);

- orbitofrontal paroxysms (complex partial seizures with motor/gestural automatisms, olfactory hallucinations, autonomic disorders);

- combined medial frontal seizures (seizures resembling those caused by damage to various medial structures of the frontal lobe);

- dorsolateral seizures (tonic or clonic, may be combined with adversion of the head and/or eyes, speech cessation);

- “cingular” paroxysms (complex focal attacks with motor automatisms, autonomic symptoms, affective disorders);

- Kozhevnikov syndrome (well-localized partial motor seizures);

- Rasmussen's syndrome (partial motor or sensorimotor seizures combined with motor deficits due to unilateral brain damage);

- frontal autosomal dominant epilepsy with nocturnal paroxysms (nonspecific aura followed by the appearance of dyspnea, vocalization, pathological motor activity or hyperkinetic manifestations, reflex arousal with postural changes) [2, 6, 7, 13].

Temporal lobe epilepsy. Polymorphism of attacks: simple and complex partial, as well as secondary generalized, occurring separately or serially. Often accompanied by vegetative and mental disorders, sensorimotor phenomena (hallucinations, etc.). There are medial and lateral attacks. The appearance of unilateral clonic or tonic seizures, unilateral dystonia or automatisms in patients is regarded as a sign of lateralization [2, 6, 7, 13].

Parietal epilepsy. Simple partial (usually in combination with sensory phenomena) and secondary generalized paroxysms are typical for it. In this form of epilepsy, the following are considered: posterior parietal seizures (frozen gaze, immobility, visual phenomena, disturbances of consciousness), anterior parietal seizures (most often in the form of positive or negative sensory phenomena), inferior parietal seizures (dizziness, discomfort in the abdomen, disorientation in space ) and paracentral (with pathological sensations in the genital area on the contralateral side, rotational movements or postural disturbances), as well as parietal attacks emanating from the dominant (receptive/conductive speech disorders) and/or non-dominant (asomatagnosia, metamorphopsia) hemispheres [2, 6 , 7, 13].

Occipital epilepsy. Its peculiarity is positive and/or negative visual phenomena that occur on the side contralateral to the epileptogenic focus. Other manifestations are turning the head to the side, abduction (tonic, clonic) of the eyes - usually in the direction opposite to the localization of the epileptic focus; blinking, nystagmoid twitching. Epileptic discharges can spread to other parts of the brain: temporal, frontal, supplementary motor or parietal areas [2, 6, 7, 13].

The first-line drugs of choice for focal seizures and symptomatic partial epilepsies are carbamazepine, phenytoin and oxcarbazepine, the second line of choice are topiramate, levetiracetam and lamotrigine [13, 14]. Topiramate deserves special attention - an AED from the class of sulfamate-substituted monosaccharides, which has the properties of exceptional utilization and bioavailability, and the absence of antitherapeutic interactions with other anticonvulsants [15].

Most AEDs have a relatively high potential for unwanted interactions when prescribed as part of complex therapy. In this regard, a number of advantages of topiramate are obvious. 2nd generation AEDs must have two main properties: an effectiveness no less than or greater than that of 1st generation anticonvulsants; less number and severity of side effects [15]. Topamax (topiramate) fully meets these requirements.

Not all mechanisms of action and pharmacological properties of topiramate have been studied, but its effectiveness in partial and generalized seizures has been experimentally established. Its antiepileptic activity was confirmed in biochemical and electrophysiological studies on neuron cultures. Topiramate reduces the frequency of action potentials characteristic of neurons in a state of persistent depolarization, which indicates that the blocking effect of the drug on Na channels depends on the state of the neurons. Topiramate potentiates the activity of gamma-aminobutyrate in relation to some subtypes of GABA receptors and modulates the activity of GABAA receptors themselves, does not affect the activity of N-methyl-D-aspartate and NMDA receptors and inhibits the activity of some carbonic anhydrase isoenzymes [15, 16].

White HS et al. (2007) emphasize that topiramate limits glutamate-mediated excitotor neurotransmission by acting on more than one molecular target, that is, there are grounds and direct indications for the use of this AED in refractory forms of epilepsy [16]. In the Russian Federation, the drug “Topamax” has been used since 2003.

At therapeutic concentrations of topiramate in the blood, only 13–17% of the drug is bound to plasma proteins, and the pharmacokinetic profile of topiramate is characterized by rapid and almost complete absorption. Linear pharmacokinetics allows us to predict possible changes in plasma concentrations of topiramate under different dosage regimens.

The drug is used regardless of food intake. The frequency of administration of topiramate can be 1–2 times a day, a steady-state concentration is achieved within 1 week [15].

Partial seizures with (or without) secondary generalized tonic-clonic seizures are most common in patients of any age. Topiramate is indicated for use as part of mono- and polytherapy for epilepsy in adults and children (over 2 years old) in the presence of initial partial seizures or generalized tonic-clonic seizures; it is a means of complex treatment of pharmacotherapy-resistant seizures associated with refractory epileptic syndromes.

In monotherapy, the recommended minimum effective dose of topiramate in children is about 6 mg/kg/day, and when used in combination with other AEDs in childhood, the therapeutic dose range varies from 5 to 9 mg/kg/day [15].

Publications by Ritter F. et al. (2000), Holland KD and Wyllie PE (2000), Wheless JW (2000) and Villeneuve N. (2002) indicate the effectiveness of topiramate in children with various epileptic syndromes accompanied by localization-related seizures, generalized seizures, infantile spasms and others types of refractory epilepsies [17–20]. Verrotti A. et al. (2007), based on observations of a representative group of patients, provide data on the effectiveness of topiramate in the treatment of frontal lobe epilepsy (monotherapy regimen) [21].

Our own 5-year experience of using topiramate for epilepsy in children now allows us to confirm the data presented by foreign colleagues, as well as to state the cognitive-modulating (stimulating) effect of the drug when used in mono- and polytherapy regimens. The most obvious positive effect of the drug in children with epilepsy is on such parameters of cognitive functions (CF) as attention, memory, motor coordination and operational activity (verbal and computer testing using the Psychomat system).

In accordance with the hypothesis of Ketter TA et al. (1999), all known AEDs have positive or negative psychiatric effects (stimulant or suppressive effects of varying severity), and topiramate is an AED with a “mixed profile of psychiatric effects” [22]. Zozulya I. S. et al. (2005) indicate that topiramate belongs to GABA agonists, which explains its neuroprotective and antihypoxic effects - a substrate of cognitive-modulating effects [23]. Zullino DF et al. (2007) consider topiramate as a cognitive-modulating agent along with AEDs such as lamotrigine and levetiracetam [24].

Although side effects are possible with the use of topiramate, the drug is to a much lesser extent characterized by such effects as agitation, induced emotional lability, aphasia, amnesia, diplopia, anorexia, nausea, nystagmus, nephrolithiasis, visual and speech disturbances, as well as perversion of taste. Loiseau P. (1996) indicates that the tolerability of topiramate in most patients is significantly better than that of almost all traditional AEDs.

An extremely important point is the drug interaction of AEDs. The administration of phenytoin or carbamazepine as part of complex therapy using topiramate leads to a decrease in the content of the latter in the blood plasma, which should be taken into account in combination therapy for epilepsy.

The addition of topiramate to therapy with other AEDs (valproate, carbamazepine, phenytoin, phenobarbital, primidone) has virtually no effect on their blood concentration levels. Only in rare cases does the addition of topiramate to phenytoin therapy induce an increase in the concentration of the latter. Addition of valproate to Topamax therapy or withdrawal of valproate is not accompanied by significant changes in the concentration of topiramate in the blood.

The undeniable advantages of the drug Topamax are high bioavailability and rapid absorption in the gastrointestinal tract (GIT), weak binding to plasma proteins, linear pharmacokinetics, a pronounced half-life and an adequate period of equalization of the concentration of topiramate. Of great importance is the absence of a decrease in the concentration of other AEDs and pharmacokinetic interactions with them, as well as the cognitive-modulating effect of topiramate [15].

Aldenkamp AP (2005) states that two main strategies should be considered in the treatment of epilepsy: seizure control and adequate cognitive functioning; None of these aspects should be ignored or achieved at the expense of the other [25]. This statement is absolutely true when applied to pediatric patients with localization-related epilepsy.

Literature

- Epilepsy. In the book: “Clinical recommendations. Pediatrics 2005-2006” / Ed. Baranova A.A. M.: GEOTAR-Media. 2007. pp. 188–210.

- Arzimanoglou A. et al. Aicardi's epilepsy in children. - 3rd ed - Philadelphia-Tokyo. Wolters Kluwer. 2004.

- Studenikin V. M. et al. Epilepsy in children and its treatment // Pharmateka. 2002. ‡‚ 1 (54). pp. 48–52.

- Child Neurology (Menkes JH et al). — 7th ed. Philadelphia-Baltimore. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. 2006.

- Studenikin V.M. et al. Epilepsy in children: diagnosis and treatment // Attending Physician. 2003. ‡‚ 2. pp. 60–64.

- Wallace SJ, Farrell K. Epilepsy in children. London. Arnold Press. 2004.

- Epileptic syndromes in infancy, childhood and adolescence (Roger J. et al). Montrouge. John Libbey Eurotext. 2005.

- Register of Medicines of Russia "Encyclopedia of Medicines". Ed. 15th. M.: RLS-2008.

- Zvonkova N. G. et al. Alternative methods of treating epilepsy in children // Issues. modern ped. 2005. T. 4. ‡‚ 4. pp. 28–32.

- Freeman JM et al. The ketogenic diet. A treatment for children and others with epilepsy. New York. Demos. 2007.

- Hartman AL et al. The neuropharmacology of the ketogenic diet //Pediatr. Neurol. 2007. V. 36. P. 281–292.

- Gaby AR Natural approaches to epilepsy // Altern. Med. Rev. 2007. V. 12. P. 9–24.

- Brown T. R., Holmes G. S. Epilepsies with onset at any age: symptomatic and probably symptomatic focal epilepsies. In the book: Epilepsy. Clinical guidelines. Per. from English M.: BINOM. 2006. pp. 57–72.

- Wyllie E. The treatment of epilepsy: Principles and practice. — 4th ed. Philadelphia/Baltimore. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. 2006.

- Studenikin V.M. Topiramate - a new antiepileptic drug in neuropediatrics // Doctor.ru. 2003. December. pp. 29–33.

- White HS et al. Mechanisms of action of antiepileptic drugs // Int. Rev. Neurobiol. 2007. V. 81. P. 85–110.

- Ritter F. et al. Effectiveness, tolerability, and safety of topiramate in children with partial-onset seizures//Epilepsia. 2000. V. 41. S. 82–85.

- Holland KD, Wyllie PE Use of topiramate in localization-related epilepsy in children // J. Child. Neurol. 2000. V. 15. S. 3–6.

- Wheless JW Use of topiramate in childhood generalized seizure disorders //J. Child Neurol. 2000. V. 15. S. 7–13.

- Villeneuve N. Antiepileptics // Arch. Pediatr. 2002. V. 9. P. 854–861.

- Verrotti A. et al. Topiramate in frontal lobe epilepsy // Acta Neurol. Scand. 2007. V. 115. P. 132–135.

- Ketter TA et al. Positive and negative psychiatric effects of antiepileptic drugs in patients with seizure disorders // Neurology. 1999. V. 53. S. 53–67.

- Zozulya I. S. et al. Neuroprotectors, nootropics, neurometabolites in intensive therapy for lesions of the nervous system. K.: Intermed. 2005.

- Zullino DF et al. Improvement of cognitive performance by topiramate: blockage of automatic processes may be the underlying mechanism // Prog. Neuropsychopharmacol. Biol. Psychiatry. 2007. V. 31. P. 787.

- Aldenkamp AP, Bodde N. Behavior, cognition and epilepsy // Acta Neurol. Scand. Suppl. 2005. V. 182. P. 19–25.

V. M. Studenikin , Doctor of Medical Sciences, Professor V. I. Shelkovsky S. V. Balkan Scientific Center for Children's Diseases of the Russian Academy of Medical Sciences , Moscow

Treatment of epilepsy

Treatment is a long and complex process. Even with the correct selection of medications and the complete absence of any manifestations for a long time, doctors only talk about stable remission, but not about complete elimination of the disease. The basis of therapy is medications:

- anticonvulsants (phenobarbital, clonazepam, lamotrigine, depakine and others): taken continuously to prevent seizures;

- tranquilizers (phenazepam, diazepam): eliminate anxiety and relax the body;

- neuroleptics (aminazine): reduce the excitability of the nervous system;

- nootropics (piracetam, mexidol, picamilon): improve metabolism in the brain, stimulate blood circulation, etc.;

- Diuretics (furosemide): used immediately after a seizure to relieve swelling in the brain.

If necessary, the doctor may prescribe other groups of drugs.

If medications are not effective enough, doctors may resort to surgery. The choice of a specific operation depends on the location of the pathological focus and the form of the disease:

- removal of a pathological formation (tumor, hematoma, abscess) that caused the attacks;

- lobectomy: excision of the area of the brain in which the epileptogenic focus occurs, usually the temporal lobe;

- multiple subpial transsection: used when the lesion is large or cannot be removed; the doctor makes small incisions in the brain tissue that stop the spread of excitation;

- callosotomy: dissection of the corpus callosum, which connects both hemispheres of the brain; used for extremely severe forms of the disease;

- hemispherotopia, hemispherectomy: removal of half of the cerebral cortex; the intervention is used extremely rarely and only in children under 13 years of age due to the significant potential for recovery;

- installation of a vagus nerve stimulator: the device constantly stimulates the vagus nerve, which has a calming effect on the nervous system and the entire body.

If indicated, osteopathy, acupuncture and herbal medicine can be used, but only as a supplement to the main treatment.

Make an appointment

Principles of treatment

Doctors emphasize that with timely initiation of treatment for focal frontal epilepsy in both adults and children, the prognosis is quite favorable : in most cases, it is possible to achieve cessation of attacks and long-term remission.

When selecting a treatment regimen, adhere to the following tactics:

- Therapy always starts with one drug and its minimum dose (naturally, taking into account age-related characteristics).

- If the desired result is absent, the dose is increased to the maximum tolerated. If this again does not bring any effect, an additional examination is carried out to clarify the diagnosis.

- The necessary medication is selected depending on the characteristics of the clinical course of the disease, the frequency and type of epileptic seizures. Preference is given to modern drugs; previously used phenytoin and phenobarbital are practically not prescribed due to severe adverse reactions. Valproate and lamotrigine have proven themselves to be effective in both generalized and partial seizures and absence seizures. In addition to high therapeutic effectiveness, these medications have a prolonged effect. This is primarily convenient for the patient - it is enough to take the medicine 1-2 times a day, in addition, the risk of adverse reactions is much lower due to the stable concentration of the drug in the plasma.

- Polytherapy is possible only if there is no effect from taking any one anticonvulsant.

- When selecting the main treatment, the need for therapy and identified concomitant diseases is always taken into account.

Once stable remission is achieved (at least 2–3 years after the last attack), gradual withdrawal of medications is possible .

Important! If there is no result from drug therapy for frontal epilepsy (in addition, for temporal-frontal epilepsy and other focal forms of the disease) and provided that the pathological focus is clearly visualized on MRI, surgical intervention is suggested .

More detailed information can be obtained from our operators by phone 8(969)060-93-93.

Complications

The most serious complication of epilepsy is status epilepticus. This condition is characterized by consecutive attacks of convulsions, between which the person does not come to his senses. This condition requires emergency medical attention due to the high risk of cerebral edema, respiratory arrest and palpitations.

A sudden onset of epilepsy can cause a fall and injury. In addition, frequent attacks and lack of quality treatment leads to a gradual deterioration of mental activity and personality degradation (epileptic encephalopathy). This is especially true for alcoholic epilepsy.

Status epilepticus

Epistatus is any epileptic attack that lasts more than half an hour or constantly recurring (at least 30 minutes in a row) individual seizures, the interval between which does not exceed several seconds, and the patient does not regain consciousness. In the vast majority of cases, epistatus is a consequence of:

- the patient’s failure to comply with the doctor’s recommendations regarding diet and medication regimen;

- a sharp reduction in the dosage of anticonvulsants;

- switching from one medicine to another or independently replacing medications prescribed by a doctor with cheaper/more expensive or more effective ones from the point of view of the patient and his relatives;

- incorrect selection of antiepileptic drugs;

- acute infectious diseases with severe fever;

- organic damage to the central nervous system due to stroke, traumatic brain injury, neuroinfection, intoxication, neoplasm, etc.

The risk of developing status epilepticus is especially high in children and elderly patients suffering from neurodegenerative pathologies.

Important! Epistatus is an indication for urgent emergency hospitalization due to the risk of death due to severe brain damage.

First aid for an attack

If a person has developed a classic attack of epilepsy with loss of consciousness, tonic and clonic convulsions, those around them should:

- If possible, prevent injury from falling;

- lay the patient on his side;

- Carefully hold your head during convulsions.

It is strictly forbidden to place spoons, pencils and other hard objects in the patient’s mouth to avoid biting the tongue!

If the convulsions do not stop, or the attacks follow one after another, you must urgently call an ambulance.

Epileptic seizures: features, types and symptoms

Typically, focal seizures occur:

- adversive: first, a forced turn of the head and eyeballs occurs, after which the entire body and the person falls, after which a full-blown convulsive seizure begins;

- partial (Jacksonian): cramps or spastic contraction limited to only one muscle group, for example, the upper or lower extremities, face, etc. (but in some cases generalization of the seizure is possible);

- tonic postural: characterized by a strong tonic convulsion with breath holding and subsequent loss of consciousness.

Prevention and diet

Prevention of epilepsy is a healthy lifestyle. Doctors recommend:

- avoid stress and overwork;

- promptly treat any infections and inflammatory processes, including caries;

- minimize (or better yet, completely eliminate) intoxication, including alcohol and smoking;

- maintain body mass index within normal limits;

- regularly engage in sports at an amateur level, take more walks;

- get enough sleep and rest.

The diet for already diagnosed epilepsy, as well as an increased risk of its development, should comply with the principles of proper nutrition:

- sufficient quantity and correct balance of macro- and micronutrients (vitamins, minerals), as well as water;

- fractional meals in small portions;

- exclusion or sharp reduction of spices, coffee, black tea, carbonated drinks, etc.

Some forms of epilepsy can be corrected using a ketogenic diet, characterized by a minimum amount of carbohydrates, a medium amount of protein and a high amount of fat (up to 80% of all calories). The transition to this style of nutrition should only be carried out with the permission of a doctor and take place under his strict supervision.

Advantages of the clinic

The Health Energy Clinic works to make quality medical care accessible to everyone. Our advantages are:

- doctors of various specialties who regularly improve their knowledge and skills;

- modern diagnostic equipment;

- the whole range of laboratory tests;

- comprehensive health screening programs;

- individual approach to the selection of therapy;

- own day hospital;

- affordable prices for all services.

Epilepsy is a disease that forces a person to live in constant fear of a new attack. Take control of your illness and sign up for Health Energy.