Quick transition Treatment of vestibular neuronitis

Vestibular neuronitis (VN) is a disease of the peripheral vestibular system. It is characterized by the acute onset of severe systemic (rotational) dizziness and severe imbalance, which are accompanied by nausea and vomiting.

VN ranks third among all causes of peripheral vertigo after benign paroxysmal positional vertigo (BPPV) and Meniere's disease and first among causes of rotational vertigo lasting more than 24 hours.

The annual incidence of VN ranges from 3.5 to 15.5 people per 100,000 population. Both men and women are susceptible to the disease; the peak of VL occurs at 40-50 years of age.

Pathogenesis

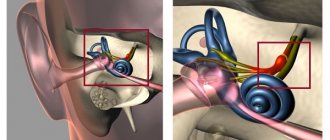

Normally (from the vestibular receptors at rest), the same sensory signal travels along the vestibular nerves in both directions. It is transmitted to the nuclei of the brain stem through the vestibular nerves. In LN, the pathological process reduces the signal from the affected side, causing an asymmetry in the tone of the brainstem nuclei. This leads to oculomotor disorders (nystagmus - involuntary oscillatory movements of the eyes), disturbances of perception (rotational vertigo), postural disorders (imbalance at rest and during movement), autonomic disorders (nausea, vomiting).

What symptoms may occur with vestibular neuritis?

When the vestibulocochlear nerve becomes inflamed, the following manifestations occur:

- Dizziness.

- Vertigo is a condition in which it seems that surrounding objects or a person’s own body are rotating.

- Impaired sense of balance.

- Nausea, vomiting.

- Impaired concentration.

- If the disease is caused by a viral infection, the body temperature rises.

Typically, symptoms of vestibular nerve neuritis occur suddenly and unexpectedly. While doing normal daily activities or waking up from sleep in the morning, a person feels severe dizziness. This can be very frightening and cause a call to the emergency room.

Usually the most severe and unpleasant manifestations of vestibular neuritis (vertigo, dizziness) only torment for a couple of days, interfere with your usual activities, and then go away. Then, over several weeks (in most cases 3 weeks), gradual recovery occurs. In some patients, dizziness and loss of balance may persist for several months.

If the disease takes a chronic course, it can be quite difficult to identify. From the outside it seems that a person is healthy, but he feels unwell - and he cannot clearly talk about his symptoms. Difficulties may arise while working on the computer, going to the store or public places, when you have to stand in the shower with your eyes closed, or turn your head. Concentration is impaired and performance suffers.

If you experience symptoms resembling vestibular neuritis, contact the Medica24 International Clinic. An experienced neurologist will establish the correct diagnosis and prescribe effective treatment.

Symptoms and course of the disease

VL is characterized by a monophasic course—an acute or subacute onset followed by subsidence of symptoms. The duration of clinical manifestations ranges on average from 1 week to 3 months (maximum manifestations range from several days to several weeks), after which the disease disappears without a trace. The probability of VN recurrence is 2-5%.

The disease begins with severe dizziness, accompanied by a certain type of nystagmus. Dizziness increases with head movements and decreases with fixed gaze. In 78% of cases, it appears suddenly; in 22% of patients, 1-2 days before the onset of the disease, phenomena in the form of instability and slight loss of coordination of movements are noted. Oscillopsia is often observed - unclear visual perception of surrounding objects when performing passive or active head movements due to instability of the image on the retina. Coordination of movements and balance are sharply impaired. Almost all patients experience nausea, and 65% have vomiting.

During the first day, the patient lies in bed - the slightest movements of the head provoke nausea and vomiting. On the 2-5th day, the patient is able to move within the room (ward), but the gait remains unsteady, and sudden head movements or walking long distances provoke nausea. On the 10-14th day, the patient complains of “heaviness” in the head and fatigue, but overall he feels healthy and can return to his usual lifestyle.

In the first days of the development of the disease, the brain “understands” that the vestibular apparatus is transmitting an incorrect sensory signal: the healthy labyrinth is always in an active state, the other (affected) labyrinth is depressed, which is interpreted by the brain as a constant rotation in the healthy direction. Since it is impossible to restore conduction along the affected vestibular nerve in a short time, the brain blocks the activity of the healthy labyrinth, aligning the flow of sensory signals from both vestibular apparatuses. As the vestibular nerve recovers, the control system returns to its original, healthy state.

Vestibular neuronitis

A neurological disease characterized by damage to the vestibular nerve, which corresponds to all the signs of an inflammatory process, accompanied by severe dizziness and loss of balance, is called vestibular neuronitis. At its core, the disease is a syndrome of acute disorder of the vestibular apparatus in the form of a continuous attack of dizziness , the duration of which can range from several hours to several days.

The pathology was identified at the beginning of the twentieth century, and since then it has been actively studied by neurologists. Vestibular neuronitis in the vast majority of cases is diagnosed in adulthood. The disease has a pronounced seasonal nature and is most often diagnosed at the turn of spring and summer. To date, the question of the causes of the pathological disorder remains open. However, neurologists are unanimous in their opinion that damage to the vestibular nerve is a consequence of viral inflammation. As evidence of the viral nature of vestibular neuronitis, we can cite cases where herpetic encephalitis occurred against the background of this pathology, that is, the cause is the herpes virus. There is also an assumption that vestibular neuronitis is a consequence of infectious and allergic processes in the human body, and the inflammation itself is an autoimmune process.

Forms of the disease

As we said above, the main symptom of the disease is a paroxysm of transient systemic vertigo . The disease occurs in acute and chronic forms. The acute form of the pathology poses the least danger to health. This is due to the relatively short course of the disease. The chronic form of vestibular neuritis is characterized by sudden attacks of dizziness and resembles a disease such as middle ear . The danger of this form of the disease for a person is that the symptoms of the pathology will remain with him (the person) for life. In addition to dizziness , vestibular neuronitis is accompanied by balance disorders, general weakness, nausea and vomiting. It is worth noting that symptoms often increase when trying to change the position of the body, when moving and turning the body. Sometimes the patient begins to feel as if objects are rotating around him. A characteristic difference between the pathology and disorders with similar manifestations is the absence of hearing .

Diagnosis and treatment

Treatment is carried out by a neurologist . Diagnosis of vestibular neuronitis is carried out through special tests and neurological tests. The most used diagnostic techniques are the Romberg position and the caloric test. Treatment is primarily aimed at eliminating the causes that provoked the pathology and reducing symptoms. Drug therapy is accompanied by physiotherapeutic procedures and therapeutic exercises. Treatment is carried out in a hospital under the constant supervision of qualified neurologists. Attempts at self-medication often lead to the opposite result, and ultimately the patient is still forced to seek help from a neurologist .

Diagnostics

In the vast majority of cases, diagnosis is based on a typical clinical picture. The diagnosis can be confirmed using videonystagmography (recording the movement of the eyeballs during a series of tests), the head impulse test (a test that evaluates the functionality of 6 semicircular canals at once - a component of the inner ear responsible for coordination) and the Fuduko test (a marching test that evaluates deviation of the patient from the original position). In addition, patients with VN exhibit spontaneous horizontal rotatory nystagmus, which intensifies when looking towards the healthy ear.

Other tests and studies, including audiometry (hearing tests) and MRI of the brain, are performed as indicated to rule out other causes of dizziness.

Differential diagnosis

VN is also differentiated (distinguished) from labyrinthitis, Meniere's disease, BPPV, neuroma (tumor) of the VIII pair of cranial nerves, multiple sclerosis, stroke, vestibular migraine.

Vestibular vertigo (VV) is one of the most common syndromes: about 5% of people experience it annually [1]. Prevalence of V.G. increases with age. Women suffer from vestibular disorders 2-3 times more often than men. The most common causes of VH are benign paroxysmal positional vertigo (BPPV), Meniere's disease, vestibular migraine, vestibular neuronitis, stroke, and transient ischemic attack (TIA). VH is usually accompanied by severe instability, as well as nausea and vomiting. Seizures V.G. are difficult for patients to tolerate, and anxiety and anticipation of new attacks often lead to the formation of emotional disorders that complicate vestibular compensation. All this makes it especially relevant to use and search for the most effective methods for stopping CH.

The choice of modern methods for treating CH is quite wide. In this case, effective treatment is based on identifying the cause of vestibular disorders. In our country, the contribution of cerebrovascular pathology, arterial hypertension, or diseases of the cervical spine to VH is often overestimated. Meanwhile, large studies conducted in recent years show that the most common causes of dizziness may be other diseases: peripheral vestibular analyzer disorders (BPPV, Meniere's disease, vestibular neuronitis) and migraine.

Seven principles for improving the effectiveness of CH treatment

1.

In the acute period of VH, vestibular suppressants are indicated

. Classic vestibular suppressants include antihistamines and benzodiazepines. In addition to them, some other drugs can be used: calcium channel blockers and acetyl leucine.

Antihistamines.

For CH, only those H1 blockers that penetrate the blood-brain barrier are effective. Such drugs include dimenhydrinate (50-100 mg 2-3 times a day), promethazine (25 mg 2-3 times a day orally or intramuscularly), diphenhydramine (25-50 mg orally 3-4 times a day or 10-50 mg intramuscularly) and meclozine (25-100 mg/day orally) [2, 3]. Side effects of vestibular suppressants include drowsiness, dry mouth, and confusion.

Benzodiazepines.

The inhibitory transmitter of the vestibular system is GABA, and benzodiazepines enhance the inhibitory effects of GABA, which explains the effect of these drugs in V.G. Benzodiazepines, even in small doses, significantly reduce dizziness and associated nausea and vomiting. The risk of drug dependence, side effects (drowsiness, increased risk of falls, memory loss), as well as slower vestibular compensation limit their use in vestibular disorders. The most commonly prescribed drug is lorazepam, which in low doses (for example, 0.5 mg 2 times a day) rarely causes drug dependence and can be used sublingually (at a dose of 1 mg). Diazepam 2 mg twice daily can also effectively reduce VG. Clonazepam has been less studied as a vestibular suppressant but appears to be as effective as lorazepam and diazepam. It is usually prescribed at a dose of 0.5 mg 2 times a day. Long-acting benzodiazepines, such as phenazepam, are not effective for CH [4]. A recent comparative study of the effectiveness of lorazepam and promethazine demonstrated the greater effectiveness of the latter as a drug for the relief of GV [5].

Other vestibular suppressants

. Less common vestibular suppressants include acetyl leucine and calcium channel blockers. The effectiveness of acetylleucine (currently not registered in the Russian Federation) is due to its interaction with phospholipids of cell membranes and the ability to regulate the membrane potential of neurons of the vestibular nuclei and Purkinje cells [6]. Calcium channel blockers - nimodipine, verapamil, flunarizine (not registered in the Russian Federation) and cinnarizine - block voltage-gated calcium channels of neurons in the labyrinth of the inner ear. These drugs are inferior in effectiveness to antihistamines and benzodiazepines [7]. Sometimes anticholinergics (scopolamine, platyphylline) are used as vestibular suppressants. These drugs inhibit the activity of the central vestibular structures, thereby reducing dizziness [3]. However, some side effects of these drugs, in particular drowsiness and blurred vision due to accommodation disorder, superimposed on vestibular symptoms, in some cases only worsen the condition of patients, which significantly limits their use in recent times. As a result, these drugs are more often used to prevent motion sickness rather than to treat CH.

2. Antiemetics enhance and complement the effect of vestibular suppressants in the acute period of VH.

They do not affect the severity of VH, but reduce the vegetative symptoms that often accompany it: nausea and vomiting. The most common antiemetics include phenothiazines, in particular prochlorperazine (5-10 mg 3-4 times daily). Metoclopramide (10 mg intramuscularly) and domperidone (10-20 mg 3-4 times a day, orally) - peripheral D2 receptor blockers - normalize gastrointestinal motility and thereby also have an antiemetic effect [8]. Ondansetron, a serotonin 5-HT3 receptor blocker, also reduces vomiting in vestibular disorders [9]. Side effects of antiemetics include dry mouth, drowsiness, and extrapyramidal disorders.

3.

The duration of taking vestibular suppressants and antiemetics should not exceed 2-3 days.

Vestibular suppressants and antiemetics depress the central nervous system and thus slow vestibular compensation [10, 11]. Animal studies have shown that drugs such as phenobarbital, chlorpromazine, diazepam and ACTH antagonists slow vestibular compensation and delay recovery [12]. These data served as a reason to recommend limiting the use of vestibular suppressants in acute VH (2-3 days). Moreover, this period is also reduced if possible. In practice, the reason for discontinuing vestibular suppressants is to stop vomiting. Instead of vestibular suppressants, vestibular gymnastics and drugs that stimulate central vestibular compensation are prescribed.

4. Vestibular gymnastics stimulates vestibular compensation and speeds up recovery.

Among the methods of treating diseases of the vestibular system, rehabilitation occupies a special place. There are several reasons for this, first of all, its high efficiency and sometimes the lack of a serious alternative to drug therapy. As a result, today, in accordance with international recommendations, vestibular gymnastics occupies almost the main place in the complex treatment of almost any disease of the vestibular system, be it central or peripheral vestibulopathy.

Gymnastics for vestibular disorders consists of four groups of exercises: for stabilizing the gaze, for training postural stability and gait, for sensory substitution and for habituation. Vestibular gymnastics should begin as early as possible (no later than the 1st week of the disease) [13]. Delaying the start of rehabilitation to a later time will most likely slow down vestibular compensation and prolong the period of disability. In addition to early initiation, there are several rules for vestibular rehabilitation that can increase its effectiveness: do not use monotonous exercises and select them taking into account the needs of the patient’s daily activity, take into account the patient’s cognitive functions and concomitant diseases that affect balance, take measures to reduce anxiety and depression, since these conditions make vestibular compensation difficult [14].

5. The effectiveness of vestibular gymnastics can be increased with the help of drugs that stimulate vestibular compensation.

Some substances have the property of stimulating central vestibular compensation. Animal studies have shown that amphetamine, caffeine and ACTH accelerate vestibular adaptation [12]. Among drugs, the ability to stimulate vestibular compensation was found in betahistine dihydrochloride (Betaserc), piracetam and Gingko biloba extract [15-17]. The effectiveness of these drugs is due to their effect on the neuroplasticity of the central nervous system and in some cases has been confirmed not only by experimental but also by clinical studies. Thus, the results of a placebo-controlled study [17] showed that betahistine dihydrochloride accelerates the onset of the effects of vestibular rehabilitation by 3 times in patients with unilateral non-progressive peripheral vestibulopathy resulting from labyrinthectomy for Meniere’s disease.

The duration of use of these drugs is not entirely clear, but appears to be determined by the nature of the vestibular damage and, therefore, the expected timing of vestibular compensation. If, with unilateral peripheral vestibulopathy, compensation occurs after approximately 2 months, then with bilateral, as well as with central vestibular disorders, compensation occurs much more slowly: within several months or years [18].

6. Pathogenetically based treatment is based on identifying the cause of CH.

The high frequency of diagnostic errors in VH, resulting from an overestimation of the role of vascular and cervicogenic mechanisms in the development of vestibular dysfunction, significantly reduces the effectiveness of treatment of dizziness in general. The consequence of inadequate diagnosis is the widespread use of vasoactive and nootropic drugs, the value of which in the treatment of the most common causes of VH (peripheral vestibular disorders and vestibular migraine) is small. At the same time, the possibilities of pathogenetically based drug and non-drug treatment of vestibular diseases have expanded recently due to the emergence of new drugs and the improvement of vestibular gymnastics.

Treatment of BPPV primarily involves the use of therapeutic repositioning maneuvers. Maneuvers are designed to treat canalolithiasis of various semicircular canals; Their efficiency is high and approaches 100%. Drug or surgical treatment of BPPV is not required in most cases [19].

Treatment of Meniere's disease consists of several stages. At the first stage, conservative approaches are used, which boil down to a salt-free diet, the use of diuretics and betahistine dihydrochloride. If results cannot be achieved within six months and attacks of VH continue, transtympanic injections of corticosteroids or gentamicin are performed. Finally, if these measures are ineffective, they resort to surgical treatment - labyrinthectomy, or selective neurectomy of the vestibular part of the vestibular-cochlear nerve [20-23].

Treatment of vestibular neuronitis is reduced to the use of symptomatic agents (vestibular suppressants and antiemetic drugs) in the acute period of the disease, followed by the selection of vestibular rehabilitation exercises in combination with drugs that stimulate vestibular compensation [24].

For vestibular migraine, the same drugs are prescribed to prevent attacks of dizziness as for ordinary migraine: β-blockers (propranolol or metoprolol), antidepressants (tricyclics or SSRIs), antiepileptic drugs (for example, topiramate, lamotrigine or valproic acid drugs), calcium blockers channels (for example, flunarizine). To relieve vestibular migraine attacks, in addition to vestibular suppressants and antiemetics, triptans and NSAIDs are used [25, 26].

For the treatment of central vestibular disorders, which arise, for example, due to stroke, trauma or MS, symptomatic drugs are used to reduce oscillopsia and instability [27]. Among such drugs are baclofen, memantine, gabapentin, aminopyridine, acetylleucine [28].

7. According to the

VIRTUOSO , betahistine dihydrochloride can reduce the frequency of VH attacks, regardless of the cause of their occurrence.

Betahistine was first registered in Canada in 1968 and has since been widely used throughout the world for the treatment of diseases manifested by VG. Betahistine is a strong H3 receptor antagonist and a weak H1 receptor agonist [29]. By acting on the H1 receptors of the inner ear, betahistine has a pronounced vasodilator effect [30]. The reduction in the number of attacks of dizziness during treatment with betahistine is apparently due to an increase in blood flow in the inner ear, which reduces the increased endolymphatic pressure in it, restoring the balance between the production and reabsorption of endolymph [31]. In addition, various animal studies have shown that betahistine is able to improve vestibular compensation, exhibiting direct histaminergic effects; the drug accelerates the release and metabolism of histamine by blocking presynaptic histamine H3 receptors (in the vestibular and tuberomammillary nuclei) [30].

The clinical effectiveness of betahistine has been assessed in several studies. At the same time, in a number of studies the effectiveness of betahistine was confirmed [17, 32, 33], while the results of others did not differ from the effectiveness of placebo [34].

The purpose of the recently completed international observational program VIRTUOSO was to evaluate the effects of betahistine dihydrochloride (Betaserc) at a dose of 48 mg/day in tablet form in routine clinical practice in outpatients with V.G. In this case, not only the overall clinical response during the treatment period was assessed, but also the delayed effects of treatment, determined by the frequency of attacks of VH within 2 months after completion of betahistine [35].

Study design.

The study was a prospective, multicenter, noncomparative, postmarketing observational program involving 23 medical centers and 309 patients; 305 patients completed the observational program. The program included patients who were prescribed betahistine in accordance with the instructions for use of the drug and clinical recommendations for the treatment of a disease manifested by paroxysmal V.G. Betahistine was prescribed at a dose of 48 mg/day. Treatment lasted 1-2 months; The observation period after cessation of treatment was 2 months.

The study included men and women aged 18 years and older, suffering from paroxysmal CH of known or unknown etiology, who were prescribed treatment with betaserc (betahistine dihydrochloride) at a daily dose of 48 mg. All patients consented to the use and processing of personal data. Patients included in the program could not take betahistine for 5 or more days before obtaining written consent and inclusion in the study.

Treatment efficacy measures included the number and proportion of patients with a clinical response at the end of therapy during follow-up within the program, as assessed by the VH Severity and Clinical Response (SVVSLCRE) scale. In addition, changes in the frequency of VH episodes at the end of therapy were identified during program follow-up compared with the inclusion visit among patients treated with betahistine dihydrochloride. The overall clinical response was also assessed separately as assessed by the physician and the patient, determined on a 4-point scale, where 4 is marked improvement, 3 is significant improvement, 2 is slight improvement, and 1 is deterioration. We analyzed the change in the frequency of VH episodes within 2 months after the end of therapy compared with the end of the therapy period. Finally, during treatment, regression of dizziness-related symptoms (tinnitus, hearing loss, nausea, vomiting, weakness and headache) was determined according to the physician and patient.

Research results.

The clinical effectiveness of treatment according to the SVVSLCRE scale was assessed as significant improvement, marked improvement or very marked improvement in 74.1% of cases (

p

<0.001).

The number of dizziness attacks per month while taking betahistine decreased from an average of 8.0 to 3.0 ( p

<0.001).

During the 2-month follow-up period after discontinuation of the drug, the number of attacks continued to decrease until they disappeared completely at the end of the 1st month of follow-up ( p

< 0.001). This effect persisted at the end of the 2nd month of observation.

The overall clinical response to treatment with betahistine (by the end of the 2nd month of taking the drug) according to the doctor was assessed as a marked improvement or significant improvement in 94.4% of cases, and according to the patient - in 95.4% of cases.

Betahistine also had an effect on the symptoms associated with dizziness. The effectiveness of treatment of associated symptoms was assessed as a marked improvement or significant improvement in 71.4% of cases by the end of the 1st month of taking the drug and in 90.5% of cases by the end of the 2nd month, according to both the doctor and the patient.

The observational program demonstrated the high safety of betahistine dihydrochloride and a low incidence of side effects. Only one patient dropped out of the study early due to lack of treatment effectiveness and an increase in the frequency of dizziness attacks. Sereznykh N.Ya. was not registered.

Thus, the VIRTUOSO observational program confirms the results of previously conducted studies, which indicated the effectiveness of betahistine at a dose of 48 mg/day in V.G. The study demonstrated a significant reduction in the frequency of CH attacks, regardless of the etiology of the disease. An important result of the study was the discovery of a delayed effect of treatment with betahistine: the number of attacks continued to decrease for 2 months after stopping the drug. This result may indirectly indicate in favor of stimulation of central vestibular compensation under the influence of betahistine. The low incidence of side effects confirms the good tolerability and high safety of betahistine. All these data allow us to recommend the inclusion of betahistine dihydrochloride (betaserc) in the complex therapy of various diseases manifested by VH, including not only Meniere’s disease, but also other disorders of the peripheral or central parts of the vestibular analyzer.

In general, if the above principles are followed, treatment of diseases manifested by CH can be quite effective. It seems promising to search for vestibular suppressants that do not suppress vestibular compensation, improve methods of pathogenetically based therapy and conduct clinical studies aimed at confirming the effectiveness of existing treatment options, as well as finding ways to stimulate vestibular compensation in various peripheral and central vestibular disorders.

Conflict of interest: The authors declare participation in the VIRTUOSO observational study sponsored by .

Treatment of vestibular neuronitis

The main directions of treatment for patients with VN are reducing dizziness, nausea and vomiting (symptomatic treatment) and accelerating vestibular compensation.

Symptomatic treatment includes the use of drugs that suppress vestibular function: antihistamines (dimenhydrinate); benzodiazepine tranquilizers (diazepam); antiemetics (metoclopramide hydrochloride, thiethylperazine).

Symptomatic treatment is recommended for no more than 3 days, since it slows down vestibular compensation, which leads to long-term dizziness.

The effectiveness of glucocorticosteroids, which were previously actively used in patients with LN, is currently being questioned. We do not recommend their use, as there is no convincing evidence of accelerated vestibular nerve recovery in these patients.

Despite the presumed viral etiology of VN, associated in particular with herpes simplex virus type 1, the use of antiherpetic drugs also does not accelerate the recovery process, and they should not be used in the treatment of VN.

Piracetam, Trental, Mexidol, Actovegin, Cavinton, glycine and other drugs with unproven effectiveness are not recommended for the treatment of VN.

From about the third day of the disease, patients with VL are recommended to perform vestibular gymnastics - exercises that accelerate compensatory processes, from simpler to more complex. These are exercises for fixing the gaze, training oculomotor reactions, and maintaining balance in various postures while standing and in motion.

Treatment

Treatment of vestibular neuronitis should be aimed at reducing the degree of dizziness, stopping vomiting (symptomatic therapy), as well as accelerating vestibular compensation.

Symptomatic therapy comes down to the prescription of so-called vestibular suppressants. The drug of choice in this case is dimenhydrinate in dosages of 50–100 mg 4 times a day at regular intervals. Metoclopramide, benzodiazepines, and phenothiazines may also be used. For vomiting, injectable forms of drugs are used (cerucal, latran intramuscularly). The duration of therapy with vestibular suppressants is determined by the severity and duration of the presence of dizziness; they are rarely used for more than 3 days, because symptomatic therapy with drugs of this series inhibits recovery, although it brings relief to the patient.

To restore vestibular function, the best way is to use vestibular gymnastics; you can learn more about the exercises by clicking on the appropriate link. The combined work of the vestibular, visual and proprioceptive analyzers makes it possible to correct sensory mismatch. It should be remembered that the first days of doing the exercises may lead to some deterioration in well-being, but therapy should not be stopped. The tactics of vestibular rehabilitation and the nature of the exercises directly correlate with the stage of neuronitis; you can see this relationship in more detail in the table in the figure below.

The positive use of methylprednisolone in stepwise therapy with gradual withdrawal of the drug has also been shown. The use of antiviral antiherpetic drugs (valaciclovir, acyclovir, etc.) did not show an improvement in the restoration of vestibular function.

To accelerate the development of mechanisms of central vestibular compensation in combination with vestibular gymnastics, it is recommended to use betahistine hydrochloride preparations (the original drug Betaserc) in a course with a daily dosage of 48 mg (24 mg 2 times a day or 16 mg 3 times a day). Due to the agonistic effect on H3 histamine receptors, there is an increase in the release of neurotransmitters, exerting an inhibitory effect on the vestibular nuclei in the brain stem. Research suggests that betahistine may accelerate vestibular compensation mechanisms.