Mirtazapine

Mirtazapine is a tetracyclic antidepressant that is used for depression, anxiety, insomnia, decreased appetite, and pain syndromes.

What is this analysis used for?

- To monitor drug concentrations in the blood.

When is the test scheduled?

- During therapy with mirtazapine (especially if liver and kidney function are impaired).

Synonyms Russian

“Remeron”, “Mirtazonal”, “Mirzaten”, “Avanza”, “Zispin”.

English synonyms

Mirtazapine (“Remeron”, “Mirtazonal”, “Mirzaten”, “Avanza”, “Zispin”).

Research method

Polarization fluoroimmunoassay (PFIA).

Units

ng/ml (nanograms per milliliter).

What biomaterial can be used for research?

Venous blood.

How to properly prepare for research?

- Do not eat for 2-3 hours before the test; you can drink clean still water.

- Do not smoke for 30 minutes before the test.

General information about the study

According to scientific hypotheses, depressive disorders occur when there is a deficiency of norepinephrine and/or serotonin in certain brain structures. In order to treat these pathologies, mood-stabilizing drugs are used - thymoleptics.

Mirtazapine is an antidepressant that can be used as a sedative, hypnotic, appetite stimulant, antiemetic and antihistamine. The drug is classified as a central agonist of alpha-2 adrenergic receptors, but its effect on serotonin, dopamine, histamine and some other receptors is also known. It is primarily used in the treatment of depression, but it is also effective for anxiety disorders, obsessive-compulsive disorder, panic attacks, post-traumatic stress disorder, anorexia, insomnia, headaches and migraines.

Mirtazapine is rapidly absorbed (bioavailability is about 50%), reaching maximum plasma concentrations in approximately 2 hours. Up to 85% of the drug binds to plasma proteins. When using 15-45 mg of mirtazapine per day, a stable plasma concentration of the substance is achieved by the fifth day of regular use. At therapeutic doses, the metabolism of mirtazapine has a linear dependence on the administered amount of the drug. Its average half-life is 20-40 hours. Sometimes, especially in older people, a longer half-life is observed (up to 65 hours), and in young people it is shorter. The long half-life of mirtazapine allows you to take the drug once a day (at night). The main pathways of its metabolism are demethylation and oxidation followed by conjugation. Some metabolites of mirtazapine are pharmacologically active and have the same pharmacological effects as the parent substance. The drug is completely eliminated approximately 4 days after cessation of administration, with 85% excreted in the urine and 15% through the gastrointestinal tract. About 4% of the drug can be excreted unchanged in the urine.

Mirtazapine has a relatively rapid onset of antidepressant effect, a slight sedative effect, reduces anxiety, improves memory and attention, has a hypnotic effect, and stimulates appetite. It can be used not only for depression, but also for withdrawal syndromes in narcology, to reduce pain in oncology, and to correct mood disorders in psychosomatic disorders. The drug is well tolerated in patients with somatic (cardiovascular, cancer, immunodeficiency) and neurological (epilepsy, Alzheimer's disease) diseases. Mirtazapine has a pronounced analgesic effect in the treatment of depression with an algic component, migraine and chronic tension-type headache and can be used in complex therapy in patients with chronic musculoskeletal pain.

Side effects from taking mirtazapine may include drowsiness, dry mouth, weight gain, increased appetite, constipation, dizziness and fatigue. In very rare cases, allergic reactions, fainting, myelodysplasia and agranulocytosis are possible. The occurrence of suicidal thoughts cannot be ruled out. There have been isolated cases of drug overdose in combination with other drugs, which resulted in death. Treatment with mirtazapine, like other antidepressants, should be carried out under strict medical supervision.

Determining the concentration of mirtazapine in the blood is not mandatory when using the drug, but it allows you to control the therapeutically effective dose of the drug in each specific case and the degree of its interaction with other drugs taken simultaneously.

What is the research used for?

- Monitoring drug concentrations in the blood;

- optimizing treatment control through dose adjustment;

- assessment of drug interactions between several drugs;

- overdose diagnosis;

- identification of violations of the drug administration regimen.

When is the study scheduled?

- When used alone with mirtazapine or in combination with other drugs (including those associated with concomitant diseases and conditions);

- when monitoring patients with impaired liver and kidney function taking mirtazapine;

- if the drug used is insufficiently effective and the issue of dose adjustment is decided;

- if the patient is suspected of non-compliance with the drug regimen;

- if an overdose of mirtazapine is suspected (lethargy, disorientation, drowsiness, hallucinations, tachycardia, hypo- or hypertension).

What do the results mean?

Reference values: 5 - 100 ng/ml.

The results of the study are analyzed by the attending physician taking into account the dose of mirtazapine, its regimen, the age and gender of the patient, the clinical picture of the disease, concomitant pathology and the presence or absence of adverse events.

What can influence the result?

- The level of mirtazapine in the blood is reduced by carbamazepine, phenytoin, and rifampicin.

- HIV protease inhibitors, azole antifungals, erythromycin, cimetidine, and nefazodone increase mirtazapine levels.

- In case of liver and/or renal failure, the concentration of the drug in the blood increases due to a violation of its metabolism and excretion.

Important Notes

- Mirtazapine at a dose of 30 mg once daily causes a slight increase in the international normalized ratio (INR) in patients treated with warfarin. In this regard, it is advisable to monitor it in case of concomitant use of warfarin with mirtazapine.

- Patients taking mirtazapine are advised to regularly monitor their blood sodium levels and liver and kidney function tests.

- It is unacceptable to adjust the dose and regimen of the drug on your own, without the participation of a doctor.

Also recommended

- Complete blood count (without leukocyte formula and ESR)

- Leukocyte formula

- Coagulogram No. 1 (prothrombin (according to Quick), INR)

- Alanine aminotransferase (ALT)

- Aspartate aminotransferase (AST)

- Total bilirubin

- Serum sodium

- Serum creatinine

- Duloxetine

- Fluoxetine

Who orders the study?

Psychiatrist, clinical pharmacologist.

Literature

- Anttila SA, Leinonen EV (2001). "A review of the pharmacological and clinical profile of mirtazapine". CNS Drug Reviews - 7(3): 249–64.

- Shams M, Hiemke C, Härtter S. Therapeutic drug monitoring of the antidepressant mirtazapine and its N-demethylated metabolite in human serum. Ther Drug Monit. 2004 Feb;26(1):78-84.

- Timmer CJ, Sitsen JM, Delbressine LP. Clinical pharmacokinetics of mirtazapine. ClinPharmacokinet 2000 Jun; 38(6):461-74.

- Medvedev V. E. Mirtazonal (mirtazapine) in psychiatric practice: forgotten and new opportunities. Review of Psychiatry and Medical Psychology named after. Bekhtereva No. 4. – 2011.

Mirtazapine Canon

Suicide/suicidal thoughts or clinical worsening of the disease

. In young people (under 24 years of age) with depression and other mental disorders, antidepressants, compared with placebo, increase the risk of suicidal thoughts and suicidal behavior, therefore, when prescribing Mirtazapine Canon to such patients, the risk of suicide should be weighed against the benefits of using the drug. In short-term studies, the risk of suicide did not increase in people over 24 years of age, but in patients over 65 years of age it decreased slightly.

Any depressive disorder itself increases the risk of suicide, so during treatment the patient should be monitored to identify disturbances or changes in behavior, as well as suicidal tendencies. Taking into account the possibility of suicide, especially at the beginning of treatment, the patient should be prescribed the smallest number of tablets of the drug in order to reduce the risk of overdose.

Bone marrow suppression

. Bone marrow suppression, usually manifested as granulocytopenia or agranulocytosis, is rarely observed with mirtazapine, appears mostly after 4-6 weeks of treatment and is reversible after discontinuation of treatment. The physician should pay close attention (and inform the patient) to symptoms such as fever, sore throat, stomatitis, and other signs of influenza-like syndrome. If such symptoms appear, you must stop treatment and have a blood test done.

Jaundice

. If signs of jaundice appear, treatment with Mirtazapine Canon should be interrupted.

Conditions requiring medical supervision

. The drug should be prescribed with caution, and patients should be monitored regularly and closely for the following conditions:

— Epilepsy and organic brain lesions

. Although clinical experience shows that epileptic seizures occur rarely both during treatment with mirtazapine and during treatment with other antidepressants, Mirtazapine Canon should be used with caution in patients with a history of epileptic seizures.

- Liver failure.

When mirtazapine was administered orally at a dose of 15 mg, the clearance of mirtazapine was reduced by approximately 35% in patients with mild to moderate hepatic impairment compared with patients with normal hepatic function. The mean plasma concentration of mirtazapine increased by approximately 55%.

- Kidney failure.

When mirtazapine was administered orally at a dose of 15 mg in patients with moderate (creatinine clearance 10-40 ml/min) or severe renal insufficiency (creatinine clearance less than 10 ml/min), the clearance of mirtazapine was reduced by approximately 30% and 50%, respectively, according to compared to healthy patients. The mean plasma concentrations of mirtazapine increased by 55% and 115%, respectively. In patients with mild renal failure (creatinine clearance 40-80 ml/min), no significant differences were observed compared with the control group.

- Heart diseases such as conduction disorders, angina pectoris and recent myocardial infarction.

In these cases, the usual precautions are required when prescribing Mirtazapine Canon and concomitant therapy.

-Reduced blood pressure.

- Diabetes.

In patients with diabetes, antidepressants may affect blood glucose levels. Adjustment of the dose of insulin and/or dose of oral hypoglycemic drugs may be required. Close monitoring is recommended.

As with the use of other antidepressants, the following conditions may occur when using the drug Mirtazapine Canon:

- Worsening of psychotic symptoms may occur when antidepressants are used to treat patients with schizophrenia or other mental disorders. Paranoid ideas may increase.

— The depressive phase of bipolar affective disorder during treatment can transform into a manic phase.

— Despite the fact that antidepressants are not addictive, based on post-registration experience, it turned out that abrupt discontinuation of therapy after prolonged use can cause “withdrawal” symptoms, it should be understood that these symptoms may be associated with the underlying disease. It is recommended to discontinue treatment with Mirtazapine Canon gradually.

— The drug Mirtazapine Canon should be prescribed with caution to patients with urinary disorders, incl. with prostatic hypertrophy, as well as in patients with acute angle-closure glaucoma and increased intraocular pressure (however, a negative effect of the drug is unlikely due to the fact that the anticholinergic activity of mirtazapine is very weak).

— Akathisia/psychomotor agitation. The use of antidepressants is associated with the development of akathisia, which is characterized by subjectively unpleasant or anxious arousal with increased motor activity. These symptoms are most likely to appear during the first few weeks of treatment. Increasing the dose in this case may have a negative impact on the patient's health.

- Hyponatremia. Extremely rare cases of hyponatremia have been reported with the use of mirtazapine. In patients at risk (elderly or patients taking drugs that can cause hyponatremia), Mirtazapine Canon should be prescribed with caution.

- Serotonin syndrome. With the simultaneous use of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors and other serotonergic drugs, serotonin syndrome may occur. Symptoms of serotonin syndrome may include fever, rigidity, myoclonus, autonomic nervous system dysfunction with possible rapid fluctuations in vital signs, mental status changes including confusion, irritability and agitation, progressive confusion, and coma. Caution and close clinical monitoring should be used when these drugs are coadministered with mirtazapine. If such symptoms appear, you should stop treatment with Mirtazapine Canon and begin symptomatic treatment. Based on post-marketing experience, serotonin syndrome appears to occur very rarely in patients receiving mirtazapine monotherapy.

— Use in elderly patients. Elderly patients are usually more sensitive, especially to side effects. Clinical studies have not shown that elderly patients experience side effects more frequently than other age groups, but they may be more severe, but data are still limited.

— Patients are advised to avoid alcohol while being treated with Mirtazapine Canon.

- Caution should be used when prescribing benzodiazepines concomitantly with mirtazapine.

Mirtazapine - a new generation antidepressant

S.G. Burchinsky, Institute of Gerontology of the Academy of Medical Sciences of Ukraine, Kiev

Summary

The article describes the mechanism of action of the new generation antidepressant, Mirtazapine, and provides a comparative description of the effects of this drug with other antidepressants widely used in clinical practice. The use of Mirtazapine in geriatric practice and issues of drug safety are discussed separately.

Keywords

depressive disorders, Mirtazapine.

One of the leading problems of modern psychiatry is depressive disorders, taking into account both the frequency of their development in the modern population (up to 10%), and their social, economic and psychological significance, as well as their role in the disability of the population. Accordingly, the search for highly effective tools for pharmacotherapy of depression—new drugs from the antidepressant group—becomes especially relevant in this regard.

Antidepressants are currently one of the most intensively developed groups of psychotropic drugs. For example, in the USA they occupy first place both in the number of new compounds studied and in the amount of capital investment in the creation of new drugs [19].

Considering the significance of depressive disorders in terms of their colossal role in the structure of morbidity, disability, and the economic costs of them in developed countries, the evolution of the clinical picture of depression observed over the past decades is of particular relevance, namely:

- an increase in the number of atypical, erased, comorbid clinical forms;

- increased frequency and severity of relapses;

- increased resistance to therapy with conventional antidepressant drugs - tricyclics (TADs) and serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs).

In addition, it is necessary to separately highlight the tendency towards increased polypharmacy in the treatment of depression due to an increase in the number of psycho- and somatotropic drugs taken in parallel, as well as a deterioration in the tolerability of many first-generation drugs, especially TAD [4, 31].

In this regard, in psychopharmacology there arose a need to develop new antidepressants, on the one hand, with an expanded mechanism of action, including an effect on various neurotransmitter systems, and, accordingly, with a wider range of clinical and pharmacological effects, and on the other hand, retaining a pronounced selectivity of action on individual links of synaptic structural and functional organization and, therefore, characterized by a high level of safety.

In this regard, drugs from the antidepressant group with a fundamentally different mechanism of action compared to representatives of the first generations deserve special attention, i.e. drugs with an effect not on the monoamine reuptake system, but on various receptor structures. One of these drugs is mirtazapine, a four-cyclic derivative, a noradrenergic and selective serotonergic antidepressant (NaSSA), the creation of which marked a new stage in the development of the pharmacology of these drugs.

Mirtazapine is an antidepressant with a unique mechanism of action. Unlike TAD and SSRI drugs, it does not affect the reuptake of serotonin, norepinephrine and dopamine. This drug selectively blocks alpha-2 auto- and heteroadrenergic receptors, as well as serotonin 5-HT-2 and 5-HT-3 receptors.

Why is this mechanism of action interesting from the point of view of pharmacotherapy of depression?

As is known, activation of alpha-2-autoadrenergic receptors located on the presynaptic terminals of adrenergic neurons, through a feedback mechanism, helps to reduce the release of norepinephrine from the synaptic nerve ending and, accordingly, inhibit the implementation of adrenergic processes in the brain. At the same time, alpha-2-heteroadrenergic receptors are located on the terminals of serotonergic neurons, and their activation also weakens serotonergic effects in the central nervous system. Thus, blockade of both types of the mentioned receptors promotes the activation of both serotonin and adrenergic processes, i.e. provides a mechanism for the implementation of the antidepressant effect [7, 16, 26].

In addition, mirtazapine blocks 5-HT-2 and 5-HT-3 receptors, the activation of which is associated with unwanted side effects of TADs and SSRIs, including serotonin syndrome, agitation, anxiety, sexual dysfunction, dyspeptic disorders, headache and others [27]. At the same time, mirtazapine stimulates 5-HT-1 receptors, through which the actual antidepressant and anxiolytic effects of serotonin are realized [8, 12].

Thus, mirtazapine is characterized by a high degree of selectivity with respect to its effect on serotonin and adrenergic processes in the brain. It is important to emphasize that this selectivity manifests itself not only at the receptor, but also at the systemic level, promoting the activation of serotonin and adrenergic reactions, which are most significant from the point of view of pharmacotherapy of depression.

In addition, mirtazapine has the properties of a central blocker of histaminergic H1 receptors, exhibits anticholinergic properties to a small extent and has virtually no effect on dopaminergic processes [16, 24].

As a result, the clinical and pharmacological spectrum of action of mirtazapine is characterized by the following main features:

- the presence of pronounced thymoanaleptic and anxiolytic effects;

- the fastest possible onset of clinical effect (already in the 1st week of treatment);

- the presence of sedation and normalization of sleep.

In clinical practice, the use of mirtazapine has proven to be most effective for anxiety and depressive disorders, including in patients with severe agitation, anxiety, and sleep disorders [2, 6, 7, 18, 21]. It is especially important to emphasize the effectiveness of mirtazapine in severe depression, as well as in clinical forms resistant to conventional therapy (TAD and SSRIs) [5, 7, 16, 29]. In addition, given the low potential for drug-drug interaction of mirtazapine, in some cases with severe resistant depression, it is advisable to combine mirtazapine and venlafaxine as drugs that effectively complement each other from a pharmacological and clinical point of view [17].

One of the leading clinical advantages of mirtazapine is the early onset of thymoanaleptic and anxiolytic effects. Various studies of the effectiveness of mirtazapine compared with paroxetine, citalopram, and fluoxetine revealed significantly more pronounced effectiveness of mirtazapine in the 1-4 weeks of treatment, as well as higher rates of response to therapy [7, 16, 34]. When compared with amitriptyline, mirtazapine exhibits comparable efficacy, but patients treated with mirtazapine had fewer relapses (in a 2-year study) and greater persistence of remission than those treated with amitriptyline [33].

It is important to emphasize that the spectrum of clinical effects of mirtazapine includes a positive effect on symptoms of depression that are extremely difficult to correct with other antidepressants - anhedonia, psychomotor retardation, as well as cyclothymic disorders.

Thus, mirtazapine has proven to be an effective antidepressant both in the treatment of an acute depressive episode and as part of maintenance therapy. In addition to the anxiolytic profile of the drug, especially noteworthy is its normalizing effect on sleep.

Sleep disturbances in depression are one of the most typical diagnostic signs of this pathology, reflected in the DSM-IV [13] and observed in 80-90% of depressed patients. These include disturbances in falling asleep and waking up, as well as disorganization of sleep structure. In most cases, there is a clear correlation between the severity of the affective component and the severity of insomnia [9]. In this case, sleep disturbances can precede, accompany and/or seriously worsen the course of the pathological process, and also increase the likelihood of relapse [14].

Thus, a treatment strategy aimed at normalizing sleep structure in patients with depression can be considered not so much as symptomatic, but rather as pathogenetic therapy. In this regard, mirtazapine is one of the few antidepressants with proven effectiveness in correcting insomnia disorders in patients with depression [16].

Another relevant area of application of mirtazapine is geriatric practice. This drug is one of the best in terms of both effectiveness and tolerability in the elderly and senile [20, 28]. Considering that symptoms of depression such as concomitant anxiety, sleep disturbances, anhedonia and others are especially common in old age, as well as the fact that TAD drugs are not recommended for use in this age group [1], mirtazapine should be considered as the drug of choice in gerontopsychiatry for the treatment of all forms of depressive disorders.

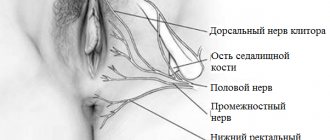

Finally, a unique and very valuable property of mirtazapine is the possibility of correcting sexual disorders with its help (decreased libido, anorgasmia, accelerated ejaculation, etc.), which, on the one hand, are often one of the concomitant clinical manifestations of depression, and on the other hand, often develop as a complication of therapy with SSRI drugs [7, 11]. The possibility of safely switching therapy from SSRI drugs to mirtazapine, as well as the proven effectiveness of combination therapy (mirtazapine + SSRI) [30], allows in some cases not only to increase the effectiveness of treatment, but also to prevent the development of sexual dysfunction - one of the most common reasons for refusal to continue taking SSRIs.

Mirtazapine is one of the safest drugs in the antidepressant group. Unlike TAD, it is devoid of cardiotoxicity, does not have the ability to cause serotonin syndrome, and exhibits anticholinergic properties to a small extent (dry mouth, dyspepsia). The drug can sometimes cause increased sedation, dizziness, and drowsiness at the beginning of treatment, which, however, rarely reach clinically significant severity and usually disappear during further treatment. A more significant side effect of mirtazapine is considered to be increased appetite and weight gain, which, however, are also more often observed at the beginning of treatment and only in some cases can cause drug withdrawal [15, 25].

In direct comparative studies, mirtazapine proved to be a significantly safer antidepressant than amitriptyline, and compared to SSRI drugs, it was less likely to cause gastrointestinal disorders. Mirtazapine also had a beneficial effect on the sexual sphere [23, 25].

Thus, using the example of mirtazapine, one can verify the effectiveness of new generation antidepressants with a dual receptor mechanism of action (HaCCA) [3, 22, 32]. The possibility of using drugs that combine in their mechanism of action the effect on various neurotransmitter systems and the high selectivity of this effect allows:

- expand the possibilities of pharmacotherapy for various clinical forms of depressive disorders;

- ensure the earliest possible manifestation of the clinical effect;

- conduct effective and safe treatment for depressive disorders in various age groups;

- significantly reduce resistance rates during treatment with antidepressants.

In addition, mirtazapine treatment has been proven to be more cost-effective than amitriptyline and fluoxetine when assessing direct and indirect costs combined [10].

Among the mirtazapine drugs on the domestic pharmaceutical market, it is worth noting the appearance of the drug Mirtazapine Hexal (Germany), which combines a high level of quality in accordance with European standards and economic accessibility. Mirtazapine Hexal is available in the form of tablets of 15, 30 and 45 mg, which allows you to effectively combine different dosage regimens and schedules and titrate the dose depending on the characteristics of the clinical picture, treatment tolerance and concomitant pharmacotherapy in a particular patient.

Further expansion of experience with the use of mirtazapine may help optimize the pharmacotherapy of depressive disorders and improve the strategy and tactics of using new generations of antidepressants.

Literature 1. Burchinsky S.G. New approaches to optimizing pharmacotherapy of depression in the elderly and senile // Ukr. Newsletter of Psychoneurol. - 2006. - T.14, VIP. 1. - pp. 62-66. 2. Kolyutskaya E.V., Yastrebov D.V. The use of mirtazapine in the treatment of depression // Rus. honey. magazine - 1999. - T. 2, No. 2-3. — P. 50-52. 3. Morozova M.A. The effectiveness of mirtazapine therapy in patients with depression and affective disorders 4. Mosolov S.N. The current stage of development of psychopharmacotherapy // Ros. honey. magazine - 2002. - T. 10, No. 12-13. — P. 64-68. 5. Palamarchuk S.A. Remeron (mirtazapine) is a new generation antidepressant. Use in severe depression (literature review) // Tavrich. magazine psychiatrist - 2000. - T. 4, No. 1. - P. 51-54. 6. Petryuk P.T., Petryuk A.P. Clinical aspects of the use of mirtazapine (Remeron) in psychiatric practice // Mental Health. - 2005. - No. 3. - P. 54-60. 7. Remeron (mirtazapine) - a new generation antidepressant 8. Pharmacotherapy of depression: fourth generation of antidepressants 9. Abad VC, Guilleminault C. Sleep and psychiatry // Dialogues Clin. Neurosci. - 2005. - Vol. 7. - P. 291-303. 10. Brown MCJ, Nimmerrichter F., Guest JP Economic impact of using mitrazapine in the management of moderate and severe depression in France // Eur. Neuropsychopharmacol. - 1998. - Vol. 8, Suppl. 2. - P. S150. 11. Clayton AH, Montejo AL Major depressive disorder, antidepressants and sexual dysfunction // J. Clin. Psychiat. - 2006. - Vol. 67, Suppl. 6. - P. 33-37. 12. Davis R., Wild MI Mitrazapine: a review of its pharmacology and therapeutic potential in the management of major depression // CNS Drugs. - 1996. - Vol. 5. - P. 389-402. 13. Fuchs E., Simon M., Schmelting B. Pharmacology of a new antidepressant: benefit of the implication of the melatonergic system // Int. Clin. Psychopharmacol. - 2006. - Vol. 21, Suppl. 1. - P. S17-S20. 14. Gillin JC Are sleep disturbances risk factors for anxiety, depressive and addictive disorders? // Acta Psychiat. Scand. - 1998. - Vol. 98, Suppl. 393. - P. 39-43. 15. Gillman PK A systematic review of the serotonergic effects of mirtazapine in humans: implications for its dual action status // Hum. Psychopharmacol. - 2006. - Vol. 21. - P. 117-125. 16. Gorman JM Mirtazapine: clinical overview // J. Clin. Psychiat. - 1999. - Vol. 60, Suppl. 17. - P. 9-13. 17. Hannan N., Hamzah Z., Omeniyi A. et al. Venlafaxine — mirtazapine combination in the treatment of persistent depressive illness // J. Psychopharmacol. - 2006. - Vol. 19. - P. 43-49. 18. Holm KJ, Markham A. Mirtazapine: a review of its use in major depression // Adis. Drug Eval. - 1999. - Vol. 57. - P. 607-631. 19. Holmer AF Survey finds 103 medicines in clinical testing for mental disorders // New Med. Develop. Mental Illnesses. - 2000. - No. 6. - P. 1-16. 20. Hoyberg OJ, Maragakis B, Mullin J et al. A double-blind multicentre comparison of mirtazapine and amitriptiline in elderly depressed patients // Acta Psychiat. Scand. - 1996. - Vol. 93. - P. 184-190. 21. Lakatos L., Rihmer Z. 1×1 or 2×1? Another form of dual antidepressive mechanism of action // Neuropsychopharmacol. Hung. - 2005. - Vol. 7. - P. 118-124. 22. Millan MJ Serotonin 5-HT-2C-receptors as a target for the treatment of depressive and anxious states: focus on novel therapeutic strategies // Therapie. - 2005. - Vol. 60. - P. 441-460. 23. Montgomery SA Safety of mitrazapine: a review // Int. Clin. Psychopharmacol. - 1995. - Vol. 10, Suppl. 4. - P. 37-45. 24. Nutt DJ Mirtazapne: pharmacology in relation to adverse effects // Acta Psychiat. Scand. - 1997. - Vol. 96, Suppl. 39. - P. 34-37. 25. Nutt DJ Tolerability and safety aspects of mirtazapine // Hum. Psychopharmacol. - 2002. - Vol. 17, Suppl. 1. - P. S37-41. 26. Pacher P., Kecskemeti V. Trends in the development of new antidepressants. Is there a light at the end of the tunnel? //Curr. Med. Chem. - 2004. - Vol. 11. - P. 925-943. 27. Pinder RM The pharmacologic rationale for the clinical use of antidepressants // J. Clin. Psychiat. - 1997. - Vol. 58. - P. 501-508. 28. Rabheru K. Special issues in the management of depression in older patients // Can. J. Psychiat. - 2004. - Vol. 49, Suppl. 1. - P. 41S-50S. 29. Richelson E. The pharmacologic rationale behind antidepressant efficacy in severe depression // J. Clin. Psychiat. - 1996. - Vol. 57. - P. 559-560. 30. Rojo JE, Ros S, Aguera L et al. Combined antidepressants: clinical experience // Acta Psychiat. Scand. - 2005. - Suppl. 428. - P. 25-31. 31. Schatzberg AF, Nemeroff CB Textbook of Psychopharmacology. —Washington: Amer. Psychiat. Press, 1998. - 598 p. 32. Stahl SM Are two antidepressant mechanisms better than one? // J. Clin. Psychiat. - 1997. - Vol. 58. - P. 339-340. 33. Stahl SM, Zivkov M., Reimitz PE et al. Meta-analysis of randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, efficacy and safety studies of mirtazapine versus amitriptyline in major depression // Acta Psychiat. Scand. - 1997. - Vol. 96, Suppl. 391. - P. 22-30. 34. Wheatley DP, van Moffaert M, Timmerman L et al. Mirtazapine: efficacy and tolerability in comparison with fluoxetine in patients with moderate to severe major depressive disorder // J. Clin. Psychiat. - 1998. - Vol. 59. - P. 306-312.