The term syringomyelia is a collective term that includes various conditions that are characterized by damage to the spinal cord with the formation of pathological cavities filled with fluid.

In 1827, the French physician Charles Prosper Olivier Angers (1796-1845) proposed the term syringomyelia, as syring from Greek means cavity (tube) and myelo means brain. Later, the term hydromyelia was used to denote enlargement of the spinal canal, and syringomyelia to denote cystic cavities without communication with the spinal canal.

Cavities in the spinal cord can be the result of a spinal cord injury, a spinal cord tumor, or a congenital abnormality. The idiopathic form of syringomyelia (a form of the disease without a specific cause) has also been described in the clinic. The fluid-filled cavities slowly expand and lengthen over time, causing progressive damage to the nerve centers of the spinal cord due to the pressure exerted by the fluid. This damage results in pain, weakness, and stiffness in the back, shoulders, arms, or legs. Patients with syringomyelia may have a varying combination of symptoms. In many cases, syringomyelia is combined with an abnormality of the foramen magnum, where the lower part of the medulla oblongata is located, which connects the brain and spinal cord. In addition, syringomyelia is often combined with Chiari malformation, in which part of the brain is displaced down to the medulla oblongata, thus reducing the spinal canal. Familial cases of syringomyelia are also sometimes observed, although this is rare.

Types of syringomyelia include:

- syringomyelia with communication with the fourth ventricle

- syringomyelia due to CSF block (without connection with the fourth ventricle)

- syringomyelia due to spinal cord injury

- syringomyelia and spinal dysraphism (incomplete closure of the neural tube)

- syringomyelia due to intramedullary tumors

- idiopathic syringomyelia

Syringomyelia occurs in about eight out of every 100,000 people. The onset of the disease is most often noted between the ages of 25 and 40. Rarely, syringomyelia can develop in childhood or in old age. Men get this disease more often than women. No geographic or racial dependence was noted. Cases of familial syringomyelia have been described.

Causes and symptoms

Most patients with syringomyelia experience headaches, often in combination with periodic pain in the arms or legs, usually more severe in half of the body. The pain may begin as dull and mild and gradually increase in intensity, or it may appear suddenly, often as a result of coughing or straining. Pain in the limbs often becomes chronic. You may also experience numbness and tingling in your arm, chest, or back. An inability to feel the ground under your feet, or tingling in the legs and feet, may also occur. Weakness in the limbs with syringomyelia leads to improper motor skills of hand movements or impaired walking. Eventually, functional use of the limbs may be lost.

The causes of syringomyelia remain unknown. No theory at present can correctly explain the basic mechanisms of the formation of cysts and cystic enlargements. One theory suggests that syringomyelia occurs as a result of pulsating cerebrospinal fluid pressure between the fourth ventricle of the brain and the spinal canal. Another theory suggests that cysts develop due to differences in intracranial pressure and spinal pressure, especially in the presence of a Chiari malformation. A third theory suggests that the formation of cysts is caused by the cerebellar tonsils acting like a piston and causing a large pressure drop of the cerebrospinal fluid in the subarachnoid space, and this action of fluid forces affects the spinal cord. Syringomyelia usually progresses slowly, and the course of the disease lasts for years. But sometimes there is an acute course of the disease, especially when the brain stem is involved.

Syringomyelia (clinic, diagnosis, treatment tactics).

Evzikov G.Yu.

Syringomyelia (clinic, diagnosis, treatment tactics).

Syringomyelia is a pathological condition that is characterized by the formation of cerebrospinal fluid cavities in the spinal cord as a result of expansion of the central canal. The term “syringomyelia” (Greek Syrinx - tube) was proposed by Ollivier in 1824. The average prevalence of syringomyelia is 7-9 per 100,000 population. The disease is more common in men (male/female ratio is 2:1). The onset of clinical manifestations of syringomyelia is often observed at a young age. The average age of onset of the disease is 30 years. In this case, the development of cavities in the spinal cord usually precedes clinical manifestations.

Syringomyelia is a syndrome characteristic of various pathological conditions leading to compression of the subarachnoid space at the level of the craniovertebral junction and the spinal cord. The classification of syringomyelia, based on etiological principles, includes:

- syringomyelia due to anomalies in the development of the posterior cranial fossa (Chiari malformation, basilar impression, arachnoid cysts in the region of the cistern magna) (Fig. 1);

— post-traumatic syringomyelia (Fig. 2);

- syringomyelia accompanying tumors of the spinal cord (usually observed with intramedullary tumors, with extramedullary tumors there are only isolated descriptions) (Fig. 3);

- syringomyelia due to spinal meningitis and arachnoiditis;

- idiopathic syringomyelia, not associated with the above pathology.

In recent years, this classification has included discogenic spinal canal stenosis at the cervical level and large foci of demyelination in the spinal cord in multiple sclerosis. The most common causes of syringomyelia are Chiari malformations type 1 and 2. According to generalized data, 84% of all cases of syringomyelia are associated with this pathology. At the same time, the absolute majority among adults are patients with syringomyelia against the background of type 1 Chiari malformation; type 2 occurs almost exclusively in childhood.

Pathogenesis.

The pathogenesis of syringomyelia remains a subject of debate to this day. The leading pathogenetic concept, starting from the middle of the last century, was the theory of WJ Gardner in 1950. The basis of this theory is the assumption that difficulty in the outflow of cerebrospinal fluid from the large occipital cistern into the spinal subarachnoid space leads to hydrodynamic impacts of the systolic cerebrospinal fluid wave from the 4th ventricle into the walls of the central canal spinal cord. The cerebrospinal fluid wave directed in the caudal direction leads to a gradual

expansion of the central canal and formation of the syringomyelic cavity. WJGardner's theory was the first to demonstrate a pathogenetic connection between the Chiari malformation, as the cause of difficulty in the outflow of cerebrospinal fluid from the 4th ventricle, and syringomyelia. Later, this theory was confirmed in the experimental work of V. Williams in 1969, who, by monitoring pressure in the ventricles of the brain and the intrathecal space of the spinal cord, showed that there is a dissociation of liquor pressure in the skull and spinal canal during block

subarachnoid space at the level of the cistern magna. This leads to the absorption of cerebrospinal fluid into the central canal of the spinal cord through its opening in the region of the 4th ventricle. The concept of V. Williams made it possible to explain the fact of a rare combination of syringomyelia in Chiari malformation type 1 with occlusive hydrocephalus at the level of the 4th ventricle. These conditions are rarely associated with each other due to the fact that the main cause of syringomyelia according to B. Williams is not the high intraventricular pressure of the cerebrospinal fluid in the area of the mouth of the central canal, which can cause ventricular dilatation, but the difference between intraventricular pressure and pressure in the spinal subarachnoid space. At the same time, the passage of cerebrospinal fluid through the foramen of Magendie in patients with Chiari malformation type 1 is not grossly impaired, and the disorder of cerebrospinal fluid circulation is limited mainly by a violation of the communication of the greater occipital cistern with the spinal subarachnoid space. The occurrence of syringomyelia after injuries of the spine and spinal cord, with stenosis of the cervical spine and intramedullary tumors shows that the cause of syringomyelia can be not only a violation of the patency of the subarachnoid space at the level of the craniovertebral junction, but also at the level of the cervical spine, and in more rare cases at thoracic level. The proposed theory made it possible to formulate the concept of “communicating syringomyelia,” which emphasized the connection of the syringomyelic cavity with the cavity of the 4th ventricle.

It should be noted that over the past decades the concept of “communicating syringomyelia” has been subject to serious criticism. This is due to the widespread introduction of MRI into clinical practice - studies of the spine, spinal cord and craniovertebral junction. In these studies, in patients with syringomyelia, in many cases there is no connection between the cavity of the 4th ventricle and

syringomyelic cyst. In some cases, the absence of a message was also confirmed morphologically. These findings allowed us to formulate the concept of “non-communicating syringomyelia”. However, a generally accepted and agreed upon pathophysiological model of “non-communicating syringomyelia” has not yet been proposed.

Modern MRI - studies of liquor circulation in the area of the craniovertebral junction - phase contrast myelography using high-field magnets in patients with Chiari malformation and syringomyelia confirm the significance of impaired liquor circulation at the level of herniation of the cerebellar tonsils, even in patients who do not have MRI signs of communication between the cavity of the 4th ventricle and the syringomyelic cyst.

T.Milhorat 2000 proposed a classification of syringomyelia based on MRI and morphological studies. He identified 3 types of lesions: communicating central canal syringomyelia, non-communicating central canal syringomyelia, non-communicating extracanal syringomyelia. According to this classification, reported syringomyelia accounts for 10–15% of all observations. It is usually combined with Chiari malformation type 2, hydrocephalus, and Dandy-Walker anomaly. Non-communicating syringomyelia accounts for 75% of all cases and is combined with Chiari malformation type 1 and basilar impression, as well as various causes of obstruction of the patency of the subarachnoid spaces at the level of the spinal canal (trauma and degenerative stenosis of the cervical spine, tumors, etc.). Non-communicating extracanal syringomyelia (about 10% of cases) is a consequence of injuries and circulatory disorders in the spinal cord with the primary formation of a cyst in the area of damage to the medulla and its gradual spread along the length of the spinal cord.

T.Milhorat's classification is convenient in that it unites all types of cystic transformation of the spinal cord, including the so-called hydromyelia (non-communicating extracanal form), however, the pathogenesis and morphology of the cysts included in this classification are different.

Experiments on animals have proven that there is an ascending flow of cerebrospinal fluid in the central canal. Its disruption can lead to expansion of the central canal of the spinal cord not only above, but also below the site of the obstruction, which well explains the presence of syringomyelic cavities below the level of pathological processes obstructing it. Modern MR studies also demonstrate the oscillatory movement of the cerebrospinal fluid in the cavity of the central canal. In systole, the CSF flow in it is directed caudally, and in diastole - cranially. However, the reasons for fluid entering the lumen of the central canal below its mouth in the cavity of the 4th ventricle in the absence of communication between the syringomyelic cyst and the ventricle are not completely clear. There is a concept that suggests the possibility of fluid exchange between the cavity of the central canal and the subarachnoid space of the spinal cord through the substance of the spinal cord, in particular through the entry zone of the dorsal roots, but it has not yet been experimentally confirmed.

The question of the possibility of spontaneous opening and drainage of syringomyelic cysts into the subarachnoid space of the spinal cord has not yet been resolved. In the literature there are separate clinical descriptions based on MR data - studies of cysts over time, demonstrating a spontaneous decrease in the diameter of the cysts. These descriptions are sporadic and no morphological evidence of long-term functioning spontaneous shunts is provided.

None of the modern theories alone can fully explain all the clinical and pathophysiological aspects of syringomyelia, therefore the pathogenetic aspects of cyst formation require further study.

Pathomorphology.

Normally, the cavity of the central canal in children is preserved during the first decade of life. Starting from the second decade, it begins to gradually become obliterated. Central canal occlusion begins in the lower spinal cord and gradually spreads cranially.

There is an original assumption that the process of obliteration of the central canal is characteristic only of humans and is associated with upright posture. During life, the central canal can be completely obliterated or remain as a small cavity. The preserved cavity is located mainly in the upper thoracic and cervical parts of the spinal cord. This way we can explain the fact that the syringomyelic cavity, which is an extension of the non-obliterated part of the central canal, is located in most cases in the cervical or cervicothoracic regions of the spinal cord. The syringomyelic cavity may also extend into the medulla oblongata (syringobulbia). In the lumen of the syringomyelic cavity, transverse septa may be found, which give it a fenestrated character. The septa, as a rule, are represented by thin membranes and divide the cyst into separate chambers with smooth walls and approximately the same transverse size. Endoscopic studies show that the septa have defects through which the fluid in the cyst moves freely between the chambers. A cavity with uneven lumen and thickened septa may have a “beaded” appearance. In the walls of the cavity there is often a proliferation of glial tissue. According to modern concepts, gliosis, revealed by morphological examination of the walls of the syringomyelic cavity, is a consequence of increased fluid pressure in the cyst. The proliferation of glial tissue is not considered as a factor predisposing to the development of a cavity, but only as its consequence.

Recently, within the framework of syringomyelia, cysts in the spinal cord that arise as a consequence of injury, ischemia or hematomyelia (extracanal form according to T. Milhorat) have also been considered. These cysts usually have an eccentric location. Until now, the question of whether all areas of cystic transformation of the brain at the site of necrosis should be included in their number or only those cysts that tend to gradually grow involving areas of previously undamaged brain tissue.

Clinic.

In most cases, the clinical manifestations of syringomyelia are slowly progressive. In 2/3 of non-operated patients, the natural course of the disease gradually leads to the development of severe disability. The rate at which symptoms progress varies. From the moment of the first clinical manifestations to the development of severe disability can take from several years to 3 decades.

With idiopathic syringomyelia, 60% of patients have a chronic, slowly progressive course, in 25% of patients episodes of progression are replaced by periods of a stationary state, and in 15% the disease can stabilize and not progress for a long time, while patients, as a rule, remain able to work for a long time .

Neurological symptoms consist of sensory, motor, vegetative-trophic disorders and pain. At the initial stage of the disease, pain may be the leading factor in the clinical picture. At the onset, pain of a pulling and aching nature is noted in the cervico-brachial region and upper extremities, less often in the back and legs. The occurrence of pain is caused by damage to the posterior horns of the spinal cord. Quite often, the pain is predominantly unilateral, which indicates an asymmetric location of the cyst and a different effect on the posterior horns of the right and left halves

spinal cord. In later stages of the disease, pain may be associated with secondary degenerative changes in the joints of the spine and limbs.

Sensitivity disorders are often presented in the form of a “collar”, “jacket”, “half-jacket”. They are segmental - dissociated in nature - pain and temperature disorders dominate with relative preservation of deep sensitivity. Characteristic are painless burns and other soft tissue injuries, which are observed in 15% of patients and are observed mainly on the hands. Disorders of pain and temperature sensitivity, as a rule, occur in places where pain was previously noted. This is due to the gradual destruction of the gray matter of the dorsal horns adjacent to the central canal region. Damage to the spinal nucleus of the trigeminal nerve can lead to loss of pain and temperature sensitivity in the outer segments of the face. Disturbances of deep sensitivity occur in the late stage of the disease with large transverse dimensions of the syringomyelic cyst. They relate to conduction disorders and are associated with stretching and compression of the posterior columns. The high tolerance of the posterior columns of the spinal cord to compression from syringomyelic cysts is associated with a high degree of myelination of deep sensory conductors.

Movement disorders occur in 60-85% of patients. Early motor disorders include muscle atrophy due to damage to the anterior horns. Since the formation of cavities begins in the cervicothoracic spinal cord, the first amyotrophies are found in the small muscles of the hand. The process may be bilateral from the very beginning or develop sequentially in each hand. Subsequently, there is a loss of weight in the muscles of the forearm, shoulder, shoulder girdle, and upper intercostal spaces.

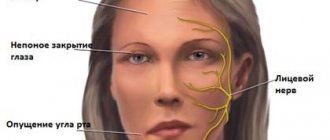

The spread of cavities into the medulla oblongata can lead to damage to n. ambiguus with the development of paresis of the soft palate, pharynx, and vocal cords. Motor disturbances from other cranial nerves are much less common. Paralysis of the facial and masticatory muscles and the external rectus muscle of the eye has been described. Asymmetrical atrophy of the tongue is typical. Nystagmus, both horizontal and vertical, is often observed. Destruction of the sympathetic centers in the spinal cord is accompanied by the appearance of Horner's syndrome on one or both sides. In the case of conductive compression of the pyramidal tracts in the lateral columns, lower spastic paraparesis occurs. The functions of the pelvic organs are rarely impaired.

Trophic disturbances are very characteristic. Tissue hypertrophy can be observed on half the body, one limb, or even in the tongue. Neuroosteoarthropathy (Charcot's joints) is observed in 20% of cases. The most commonly affected joints are the shoulder and elbow joints, less commonly the joints of the hand and temporal

mandibular, sternoclavicular and clavicular-acromial. Typically there is no pain with severe osteoarticular changes. The affected joint is often enlarged in size, and movement in it is accompanied by loud crepitus.

Trophic skin changes include cyanosis, hyperkeratosis, hyperhidrosis, thickening of the subcutaneous fat layer, especially on the hands; swollen fingers take on the appearance of a “banana bunch.”

As mentioned, loss of pain sensitivity makes you extremely susceptible to repeated injury; healing occurs slowly. Purulent inflammation of the soft tissues of the distal phalanges and bone necrosis may be observed.

The most distinct symptom complex is observed in syringomyelia against the background of craniovertebral anomalies and in idiopathic cases. With the development of cysts against the background of stenosis of the cervical spinal canal or intramedullary tumors, clinical manifestations of syringomyelia

may be mildly expressed and masked by disorders associated with the primary pathological process.

Separately, it is necessary to dwell on extracanal syringomyelia, which occurs as a result of hematomyelia, ischemia or post-traumatic necrosis of brain tissue. In this case, the core of the clinical picture is formed at the time of primary damage to the spinal cord - trauma or stroke.

We can talk about the clinical significance of syringomyelia only in cases where the clinical manifestations of spinal cord lesions begin to progress several months or years after the primary lesion, and neuroimaging reveals an intramedullary cyst spreading beyond the primary lesion. Considering the eccentric location of such cysts, typical clinical manifestations of syringomyelia (segmental dissociated sensitivity disorders) practically do not occur.

Neuroimaging.

The main method of instrumental diagnosis of syringomyelia is MRI, in which the size, localization, extent and internal structure of the cavity in the spinal cord, the condition of the subarachnoid spaces of the spinal cord, as well as possible pathomorphological changes that caused the development can be assessed.

syringomyelia (cerebellar ectopia, basilar impression, spinal cord tumor, etc.). MRI – the study should include scanning in T1 and T2 modes with the obligatory study of sagittal and coronal sections of the spinal cord. MR – the signal from the contents of syringomyelic cysts is isointense relative to the cerebrospinal fluid.

The study should begin at the level of the most pronounced clinical manifestations. If a syringomyelic cyst is detected, the upper or lower pole of which is not determined, the study must be expanded to include other parts of the spine until the boundaries of the cavity are completely visualized. If syringomyelia is detected, it is necessary

also scanning the cranio-vertebral junction to identify possible anomalies in the structure of this area and additional administration of contrast if an intramedullary tumor is suspected. The walls of the syringomyelic cavity never accumulate a contrast agent, and the MR signal from the contents of the cavity also does not change after the administration of a contrast agent. By the shape of the contours of the cyst in the sagittal plane in the region of its poles, one can indirectly judge the pressure in the cavity. Cysts with a rounded pole contour have high pressure, while cysts with a pointed contour have low pressure.

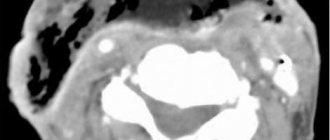

Computed tomography can also visualize a syringomyelic cyst. It provides information on axial sections, where cystic transformation of the brain is determined as a bull's eye sign. More informative is a study at the level of the cervical spinal cord, however, the segmental extent of the cyst according to CT scans is difficult to assess. Sagittal reconstruction of the spinal canal structures is based on axial sections, and visualization of the cyst at the thoracic level is difficult. The segmental extent of cysts in the sagittal projection is much better assessed when performing MRI.

Treatment.

The treatment tactics for syringomyelia are determined by the reasons for its development and the nature of its course. In the absence of progression of symptoms in idiopathic variants and against the background of craniovertebral anomalies, dynamic observation is possible. In the case of a progressive course -

surgical treatment. In case of syringomyelia against the background of spinal canal stenosis or spinal cord tumor, treatment tactics are determined not by the syringomyelic syndrome, but by the state of the pathological process causing syringomyelia.

The development of surgical techniques for syringomyelia reflects the evolution of ideas about its pathogenesis. First attempts at treatment

Syringomyelia was pioneered by Abbe and Coley in 1892. They opened and emptied a syringomyelic cyst, the formation of which was regarded as a degenerative process of the spinal cord. In 1926, Puusepp published 2 cases of opening the syringomyelic cavity with subsequent improvement in the clinical condition of the patients. After this, syringostomy operations began to be gradually introduced into practice, however, in most cases they did not produce a lasting clinical effect because were carried out without taking into account the possible etiological mechanisms of the development of syringomyelia.

The pathogenetic mechanisms described by WJ Gardner and B. Williams provided the theoretical basis for the emergence of modern methods of surgical treatment of syringomyelia. Currently, the treatment of syringomyelia has two directions: 1) elimination of the cause of syringomyelia, 2) drainage of the syringomyelic cyst.

Depending on the etiology of the disease, eliminating the causes of syringomyelia may involve removing spinal cord tumors, eliminating spinal canal stenosis, as well as various modifications of operations for anomalies of the craniospinal junction. Elimination of the causes of syringomyelia creates conditions for stopping the growth of cysts. After total removal of intramedullary tumors, in most cases, the cysts collapse.

The most difficult problem is the choice of surgical method for syringomyelia, which occurs against the background of anomalies of the craniovertebral junction. WJ Gardner, in accordance with his theory, proposed an operation that was designed to eliminate compression of the hindbrain structures in the foramen magnum as a causative factor in the formation of a syringomyelic cyst. It consisted of a wide resection of the squama of the occipital bone and the arch of the first cervical vertebra, dissection of adhesions and adhesions in the area of the Magendie foramen, revision of the mouth of the central canal and packing it with a fragment of muscle tissue.

The operation was completed with plastic surgery of the dura mater to form the cistern magna.

B. Williams' concept served as the basis for changing the operational methodology. To eliminate dissociation of craniospinal pressure, the author recommended the following elements of operative technique:

1. Economical resection of the squama of the occipital bone to prevent further descent of the cerebellum into the bone defect;

2. Resection of the cerebellar tonsils to prevent secondary occlusion of the cerebrospinal fluid pathways;

3. Closing the entrance to the central canal with a muscle fragment, which was fixed with a silicone ball over the entrance to the central canal and a suture to the posterior surface of the medulla oblongata to prevent its displacement.

Early publications on the results of operations by W.J. Gardner and B. Williams were optimistic, however, a high level of postoperative mortality was subsequently noted - 10%, which led to an almost complete abandonment of their use.

In recent decades, the practice of closing the central canal orifice has been subject to serious criticism. Analysis of the results showed that closing the entrance to the central canal does not provide advantages compared to operations without these procedures. A concept that has emerged in recent years

“non-communicating syringomyelia”, confirmed by MR studies, completely rejects the pathogenetic advisability of packing the mouth of the central canal in most patients.

Currently, there is no standard volume of intervention on the structures of the craniovertebral junction and posterior cranial fossa for syringomyelia against the background of craniovertebral anomalies. In the most radical version, modern operations include resection of the posterior hemiarch of the atlas (and, if necessary, the second cervical vertebra), resection of the squama of the occipital bone, followed by opening of the dura mater,

dissection of adhesions in the area of the foramen of Magendie and subpial resection of the cerebellar tonsils or without it. The intervention ends with plastic surgery of the dura mater to form the occipital cistern magna. However, a significant part of surgeons believe that operations of this volume are inappropriate. It is enough to limit the intervention to durotomy and plastic dura mater, but not to open the arachnoid membrane and manipulate in the area of the Magendie foramen. This position is justified by the fact that in Chiari malformation type 1 (most patients with anomalies of the craniovertebral junction in adults), hydrocephalus is extremely rare, which means that the flow of cerebrospinal fluid through the foramen of Magendie is preserved, despite the descent of the cerebellar tonsils and their adhesion to the medulla oblongata. The main obstacle to the flow of cerebrospinal fluid, creating a dissociation of craniospinal pressure, is the absence of a large occipital cistern of sufficient volume and its connection with the cerebrospinal fluid spaces of the spinal cord. Therefore, the main goal of the operation is osteodural decompression of the craniovertebral junction, after which, against the background of a decrease in pressure in this area, the cistern is gradually formed due to stretching of the previously compressed arachnoid membrane. Another argument for refusing to open the arachnoid membrane, according to supporters of reducing the scope of the operation, is the inevitability of re-formation of adhesions around the Magendie foramen after their single dissection.

In an even more simplified version, surgery for Chiari malformation type 1 can be limited to bone decompression, dissection of the compacted atlanto-occipital membrane, which in these patients is often presented in the form of a dense constriction covering the dural sac, and dissection of the dura mater. Dissection or removal of the outer layer of the dura mater, according to the authors, allows the membranes to gradually stretch on their own under the pressure of the cerebrospinal fluid. After delamination of the dura mater, it is also possible to suture the membrane to the muscles without

its dissection. In this case, a decrease in pressure in the area of the craniospinal junction occurs against the background of stretching of the dura mater due to special sutures placed extradurally. Thus, extradural operations also involve the formation of a large occipital cistern, but only due to stretching of the dura mater.

Currently, about 20 surgical techniques have been proposed aimed at improving cerebrospinal fluid circulation in the area of the craniovertebral junction. There are a large number of proprietary techniques that include durotomy and dura mater plastic surgery and do not include complete dissection of the dura mater. A randomized multicenter study has not been conducted to compare the effectiveness of craniovertebral decompression with and without durotomy, which does not allow us to judge the effectiveness of operations from the standpoint of independent expertise. The descriptions of the advantages and disadvantages of various methods given in the literature are based on the opinions of individual authors demonstrating their own series of observations. Proponents of interventions without dissection of the dura mater point to a lower incidence of complications, an easy course of the postoperative period and rapid postoperative rehabilitation. Proponents of the use of durotomy and subsequent dura plastic surgery indicate a higher effectiveness of the intervention, especially in the long-term postoperative period.

In general, considering the evolution of surgical interventions for craniovertebral anomalies in combination with syringomyelia, it can be stated that, despite the lack of a unified standard of operations, the intervention technique in recent years has evolved from the most aggressive to more gentle methods, allowing to speed up the postoperative rehabilitation of patients.

Separately, it is necessary to note the peculiarities of treatment tactics for a small group of patients with Chiari malformation in combination with syringomyelia and hydrocephalus (rare cases with type 1 anomaly and frequent cases with

type 2 anomaly, found mainly in children). As the first stage of surgery in these patients, it is advisable to use ventriculoperitoneal shunting, in which regression of the syringomyelic syndrome and collapse of the syringomyelic cyst are possible without intervention at the cranio-vertebral junction. Cranial surgery

vertebral junction in these patients can be performed as a second stage if shunting is ineffective.

Another group of patients that requires a special approach to treatment is cases of a combination of basilar impression, Chiari malformation and syringomyelia. In these patients, a decrease in the size of the posterior cranial fossa and a caudal dislocation of the cerebellum with a block of the occipital cistern magna may be associated with a high position of the tooth of the second cervical vertebra. The first stage of surgical treatment is anterior decompression of the craniovertebral junction - transoral tooth resection, which can be performed without intervention on the structures of the posterior cranial fossa. If there is no clinical effect from anterior decompression, the operation can be supplemented with standard osteodural decompression from the posterior approach. In such cases, decompressive intervention from the posterior approach should be supplemented by fixation surgery.

After operations on the craniovertebral junction, in cases of normalization of cerebrospinal fluid dynamics and elimination of dissociation of craniospinal pressure, the clinical manifestations of syringomyelia can stabilize or decrease even without significant neuroimaging changes in the size of the syringomyelic cyst. The main purpose of the operation is

prevention of further growth of cysts and stopping the progression of syringomyelic syndrome.

Since the recognition of the WJ Gardner theory, a decrease in the frequency of syringoshunting operations has been noted, since the most common cause of syringomyelia is the Chiari malformation, and the basis of the surgical technique

for this pathology, operations on the cranio-vertebral junction began. With the development of microsurgical technology and the use of modern non-reactive shunt systems, a number of authors are returning to their implementation. Currently, these operations are performed, as a rule, for idiopathic syringomyelia or in the absence of effect after operations at the level of the cranio-vertebral junction. The most common technique is syringosubarachnoid shunting. The approach consists of laminectomy (hemilaminectomy) of one vertebra at the lower level of the widest part of the cyst. A 5 mm myelotomy is performed either in the DRERZ zone or in the area of the most thinned area of the spinal cord. A silicone catheter used for lumboperitoneal shunting is inserted into the syringomyelic cyst in the oral direction by 2-3 cm and sutured to the arachnoid membrane at the site of myelotomy to prevent its displacement. The distal end of the catheter is installed in the subarachnoid space for 2-3 cm, the arachnoid membrane is sutured. To prevent cerebrospinal fluid reflux (filling of the syringomyelic cyst from the subarachnoid space through a shunt), syringopleural and syringoperitoneal shunting have been proposed, which can also be performed using a lumboperitoneal catheter.

Complications that arise after syringomyelic surgery include: local collapse of the walls of the syringomyelic cavity with the subsequent development of adhesions, ingrowth of glial tissue into the shunt segment located in the syringomyelic cavity, as well as an uncontrolled decrease in cerebrospinal fluid pressure with the development of symptoms of cerebrospinal fluid hypotension during shunting into the pleural and abdominal cavity.

As a result of surgical treatment, the symptoms of syringomyelia with anomalies of the craniovertebral junction and in idiopathic cases are amenable to varying degrees of regression in 30-45% of patients, stabilization

process with stopping progressive deterioration is observed in 45%. The operation does not affect the course of the disease in 10-20% of patients. The mortality rate for this type of pathology currently does not exceed 1-2%.

In the presence of positive dynamics, a decrease in movement disorders occurs in 25% of patients, a regression of surface sensitivity disorders in 30% of patients, and paresthesia in 25% of patients. Relapses of the disease and its further progression after temporary improvement or stabilization are observed in 20-40% of patients. This may be due to the progression of the scar-adhesive process in the area of the craniovertebral junction, further caudal dislocation of the cerebellum into a bone defect, the development of an adhesive process at the site of the syringoshunting operation, displacement of the shunt, etc. Poor clinical prognostic factors for surgical treatment of syringomyelia include severe muscle atrophy, severe dissociated sensory disorders over most of the body surface, severe scoliosis, and a long history of the disease.

Surgical treatment of syringomyelia requires a detailed assessment of the morphological changes leading to the development of cavities in the spinal cord and the clinical manifestations of the disease. The best results of surgical treatment are observed in operations performed early after the onset of the clinical picture of the disease, because in this case, a more pronounced regression of neurological symptoms can be expected.

Diagnostics

An examination by a neurologist may reveal loss of sensation or movement caused by compression of the spinal cord. Diagnosis is usually made using magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the spine, which can confirm the presence of syringomyelia and determine the exact location of the cystic lesions and the extent of damage to the spinal cord. The most common location of cysts is the cervical or thoracic spine. The least likely location for cysts is the lumbar spine. An MRI of the head can be of diagnostic value to determine the presence of any changes such as hydrocephalus (excess cerebrospinal fluid in the ventricles of the brain). As cystic formations increase, spinal deformity (scoliosis) may occur, which can be easily diagnosed using radiography. The degree of conduction disturbance in syringomyelia is determined using EMG.

Reasons for the development of syringomyelia

The reasons that cause the proliferation of glial tissue in the spinal cord are not known at this stage. However, in medicine there are two types of the disease, which are characterized by different risk factors for its development.

True syringomyelia

This is a congenital and hereditary disease, a defect in the development of glial tissue. Why this failure occurred is unknown, but the impetus for excessive proliferation of glial cells can be an infectious disease suffered by the mother during pregnancy, or by the child himself in the first months of life. A spinal cord injury (for example, childbirth) can also be a trigger. Most often, true syringomyelia manifests itself in late preschool and early school age.

Treatment

Diagnosis and treatment of syringomyelia requires a whole team of medical specialists, including neurologists, radiologists, neurosurgeons, and orthopedists.

Treatment, usually surgical, is aimed at halting the progression of spinal cord damage and preserving functionality. Surgical procedures are often performed when there is spinal cord compression. In addition, surgical procedures are performed to correct deformities or apply various shunts. Surgeries were also performed to implant fetal tissue to close the cystic formations. Surgery results in stable or moderate improvement of symptoms in most patients. Many doctors believe that surgical treatment is necessary only for patients with progressive neurological symptoms. Delaying surgical treatment in cases where the disease progresses can lead to irreversible damage to the spinal cord and severe permanent neurological impairment.

Drug treatments (vasoconstrictors) are often prescribed to reduce swelling around the spinal cord. It is often recommended to avoid strenuous physical activity, which can increase venous pressure. Certain exercises, such as bending your torso forward, can reduce the risk of cystic growths expanding. Life expectancy in patients with progressive symptoms without surgical treatment ranges from 6 to 12 months.

Recovery and rehabilitation

Despite reports of complete neurological recovery after surgery, most patients experience stable or only moderate improvement in symptoms. Syringomyelia in children is characterized by much less pronounced sensory and pain disturbances than in adults, but a much greater risk of developing scoliosis, which is more favorable for surgical treatment. In addition, syringomyelia does not progress equally in all patients. Some patients, usually those with milder symptoms, experience stabilization of symptoms over the course of a year. A frequent complication of the progression of symptoms is the patient’s need to adapt to life due to impairment or loss of some functions. These adjustments can result in a loss of quality of life. The goal of rehabilitation is to preserve functionality as much as possible using exercises and adaptive equipment, or, especially in the case of syringomyelia in children, activities should be aimed at correcting scoliosis.

Results and discussion

All patients were diagnosed with SM after MRI, while clinical manifestations of the disease at this time were found in only 28 (70%) of them. The remaining patients had no neurological symptoms. During the observation period, patients underwent from 1 to 8 control MRI studies. According to MRI, syringomyelia in 23 of them was combined with Chiari malformation, in 10 - with signs of arachnopathy, in 1 - with extradural compression, in 4 - with shortened filum terminale syndrome. The cyst was localized throughout the spinal cord in 6 (15%) patients, in 12 (30%) - in the cervical region, in 9 (22.5%) - at the cervicothoracic level, in 10 (25%) - in the thoracic part of the spinal cord and in 3 (7.5%) - at the thoracolumbar level.

Symptoms identified when the patient sought medical help are presented in Table. 2 .

Table 2. Clinical manifestations of syringomyelia in the examined patients.

The functional status of the patients was as follows: average value on the Karnofsky scale - 74.7, average McCormick - 1.9, average mJOA - 13 points. The average length of the syringomyelic cyst was 136 mm, and the average Vacuero index was 38.2%.

The observation period for 12 (30%) patients without neurological symptoms was 62±13 months. During this time, only 1 (8.3%) patient developed sensory disturbances in the hands, which began to progress over time. This became the reason to determine her indications for surgery. The remaining patients (91.7%) continue to be monitored dynamically. Taking into account the data obtained, we can say that the presence of SM without concomitant clinical symptoms is not an indication for surgery, since the patients’ condition remains stable for a long time. Such patients should be monitored dynamically and, if neurological symptoms appear, the issue of surgical treatment should be decided. According to the literature, SM has a chronic progressive course [1–3, 10]. In our study, this course was observed in all patients. Lightning forms are described in isolated publications. If you organize regular monitoring of the patient, then surgical treatment will be carried out on time, and the risk of developing irreversible neurological disorders is minimal.

When SM was diagnosed, 28 patients had certain neurological symptoms. Despite the conservative treatment, in 17 (60.7%) patients the symptoms began to slowly progress over time. Movement disorders were most frequently aggravated. In our series, it worsened in 8 out of 10 patients with motor deficit. Dysfunction of the pelvic organs (in 3 out of 5 patients), sensory disorders (in 7 out of 24 patients) and ataxia (in 4 out of 11 patients) increased somewhat less frequently. Using the analysis of variance method, a relationship was revealed - the presence of a motor deficit in a patient with SM is a predictor of disease progression (r = 0.68). Statistical analysis methods did not reveal any other patterns.

Functional changes in the spinal cord that occur under the influence of a cyst can be irreversible, so surgery is indicated for patients with progression of the disease. The purpose of the operation is to stabilize the condition and prevent deep disability of the patient. Patients with primary motor disorders deserve special attention. The treatment strategy for such patients should be as aggressive as possible in terms of surgery.

In a minority of cases - in 8 (28.6%) patients, symptoms did not change during observation; in 5 patients in this group, complaints appeared in childhood and did not progress. An improvement in the general condition was noted by 3 (10.7%) patients, in two of them the appearance of the syringomyelic cyst on MRI did not change, and in one patient the cyst regressed on its own 2.5 years after detection. The stable condition of patients with SM can be considered as a reason for continued dynamic observation, and only if symptoms increase or the size of the cyst increases, surgery is indicated for patients.

The size of the spinal cord cyst changed over time in 15 patients. All changes occurred in patients with neurological manifestations at the onset of the disease. In 1 (2.5%) patient, the syringomyelic cyst disappeared, in the remaining 14 (35%) it increased. On average, the cyst increased by 2.1 segments, and the Vaquero index increased by 9.6%. All changes in cyst size began after 32±20 months. We have identified a relationship between an increase in cyst size and the progression of clinical manifestations of the disease. In 12 of 14 patients with cyst growth, progression of neurological symptoms was noted. The correlation coefficient between these two indicators was 0.71 (p<0.05). In 2 patients, despite the growth of cavities in the spinal cord, no new symptoms appeared. This indicates that patients with a stable or asymptomatic course require dynamic monitoring. Considering the slow change in cyst size, control MRI studies can be performed once every 12 months. However, a caveat must be made that this period between MRIs is advisable only in patients with a stable condition.

As a result of the analysis of the questionnaires, it was revealed that 36 (90%) patients, after MRI and a comprehensive examination, received one or more consultations with a neurosurgeon; 12 patients were offered surgery, which they refused. The main reasons for refusal were fear of surgery (66.7%) and insufficient patient awareness of the disease, the purpose of the operation and its risks (15%).

Based on the formulated indications for surgery (the appearance or progression of neurological symptoms), an analysis of primary medical documentation, questionnaires and MRI data was carried out. Of the 12 patients who were offered surgery, we determined the indications for only 8 people; the remaining 4 patients did not have neurological symptoms, and their cyst did not increase in size. At the same time, among the patients who, despite a complete examination, were not offered surgery, another 11 people were identified for whom it was indicated. Thus, in our study, indications for surgical treatment were identified in 19 (47.5%) patients.

Forecast

The prognosis for patients with syringomyelia depends on the underlying cause of the cyst and the type of treatment. Untreated cases of syringomyelia in 35-50% of cases have a prognosis for long-term survival. Patients who underwent bypass surgery for spinal cord injury experienced long-term pain relief and increased survival. Recent studies have shown poor long-term prognosis due to high rates of cyst recurrence in other forms of syringomyelia. Surgical treatment (posterior decompression) for syringomyelia combined with Chiari malformation is considered a fairly effective treatment with a high chance of clinical improvement. For syringomyelia in children, surgical treatment is effective in stabilizing scoliosis.