Find out more information about neurological diseases starting with the letter “F”: Phakomatoses; Phantom pain; Fibromyalgia; Focal cortical dysplasia; Focal epilepsy; Funicular myelosis.

Focal epilepsy: what is it?

This pathology is characterized by epileptic seizures caused by a clearly localized limited zone of increased paroxysmal activity. Most often they are secondary in nature. Paroxysms can be partial complex or simple. The clinical picture depends on the location. Diagnosed by clinical data. EEG and MRI are also indicated. Therapy includes antiepileptic drugs and treatment of the primary disease. According to indications, resection of the epi-zone is possible.

What are pseudoepileptic seizures?

Pseudoepileptic seizures (conversion, psychogenic, non-epileptic or hysterical seizures) are sometimes difficult to distinguish from epilepsy by external signs; however, in some patients a combination of epileptic and non-epileptic seizures is possible. The incidence of these disorders is quite high, they account for approximately 20% of all cases considered to be resistant forms of epilepsy. Attacks of this type are more common in women. The family history of patients often contains indications of mental disorders. It is more correct to consider these attacks as a manifestation of mental illness; they are not accompanied by epileptic activity on the EEG and are not controlled by anticonvulsants (unlike epileptic seizures). Pseudoepileptic seizures can have different external manifestations. Pseudoepileptic seizures can take a status course, in which case there is a risk of introducing large doses of anticonvulsants into the body and even the use of mechanical ventilation.

As a rule, these attacks do not occur when the patient is alone; witnesses are needed for their occurrence; attacks are usually provoked by a conflict situation. As a rule, during such attacks the patient does not receive injuries (even if he falls), does not bite his tongue, and there is no urinary incontinence. The onset of pseudoepileptic seizures is often gradual, cyanosis (bluish discoloration of the skin) is not observed. Convulsions in the limbs are less rhythmic than during epileptic seizures and may have the character of asynchronous, chaotic movements. The patient actively resists attempts to open his eyes during the attack. Post-ictal drowsiness or confusion is not common.

The main method of differential diagnosis is video-EEG monitoring.

Unlike malingering, patients cannot specifically induce seizures and control them. Pseudoepileptic seizures are also a disease that requires treatment, however, treatment is carried out not with anticonvulsants, but with psychotropic drugs.

general information

Focal epilepsy refers to all cases of epileptic paroxysms if they arise due to a local focus of increased epi-activity in cerebral structures. The source of excitation begins focally. Gradually spreads to the surrounding brain tissue. This provokes secondary generalization of the attack. It should be differentiated from paroxysms of unrealized epilepsy with a primary diffuse nature of excitation. There is a multifocal form. It is distinguished by the presence of several local zones of excitation.

FE accounts for approximately 82% of all epileptic syndromes. In 75% of cases, the onset occurs in childhood. Most often, the root cause is a violation of brain development of infectious, traumatic or ischemic origin. Such secondary focal epilepsy appears in 71% of patients.

What is the difference between focal and generalized epileptic seizures?

Seizures in which an epileptic discharge begins in one or more localized areas of the cortex (from one or more foci of epileptic activity) are called focal (partial, locally caused, local). Epileptic activity can then spread to other areas of the cerebral cortex. If epileptic activity spreads from the focus of epileptic activity throughout the cerebral cortex, the seizure is called secondary generalized.

Seizures in which a pathological discharge initially simultaneously affects the cortex of both hemispheres are called generalized.

In some cases, seizures do not fit into this classification and cannot be classified into one of two groups; such attacks are called unclassifiable.

Etiology and mechanism of development

Etiological factors include:

- Traumatic brain injuries.

- Malformations of the brain. These include: congenital cerebral cysts, cortical dysplasia, arteriovenous malformations.

- Infections: abscess, encephalitis, neurosyphilis, cysticercosis.

- Genetically determined or acquired metabolic disorders of neurons in a certain area of the cerebral cortex. It is not accompanied by morphological changes.

- In children, perinatal lesions of the central nervous system predominate. These are intracranial birth trauma, fetal hypoxia, asphyxia of the newborn, intrauterine infections.

- Early onset in childhood is associated with impaired cortical maturation. Such epilepsy is temporary and age-dependent.

The pathogenesis of FE is associated with an epileptogenic focus, which has several zones. The area of damage corresponds to the localization of the morphological change. Most often visualized using magnetic resonance imaging. The primary zone is the area that generates epi-excitation. The area of the cortex, the epi-activity of which leads to an attack, is the symptomogenic zone. The irritative region generates epi-activity during the interictal period. Excitation is recorded on the EEG. The zone of functional deficit is the area responsible for concomitant neurological disorders.

Causes and pathogenesis of focal epilepsy

The development of FE is preceded by the following pathologies:

- tumors of a malignant and benign nature;

- serious disturbances of metabolic processes in the body, including cerebral circulation;

- injuries of the skull and internal tissues;

- infections of any kind, for example, encephalic or meningococcal;

- violations of the structure of the intracranial substance of a hereditary nature.

The main causes of the disease include factors acquired as a result of any negative impact on the brain or caused by hereditary diseases.

Pediatric FE is mainly characterized by prenatal problems or congenital diseases. In both cases, certain areas of the cortex are affected. In particular:

- infection inside the womb;

- oxygen starvation;

- suffocation of a newborn during the passage of the birth canal;

- increased intracranial pressure;

- birth injury.

In some cases, the disease manifests itself against the background of underdevelopment of the cerebral cortex of both or one hemisphere. The likelihood that the pathology may disappear as the child grows and develops is very high.

The functional genesis of epileptic seizures with focal seizures is characterized by several zones:

- sector of epileptogenic disorder, corresponding to the area of morphological changes visible in tomographic studies;

- primary - the compartment of the cortex in which epileptic discharges are formed;

- irregular - a source of activity observed on electroencephalography and deciphered as the period between attacks;

- functional deficit - the sector in which disorders accompanying an epileptic seizure are generated.

Classification

There are three forms of focal epilepsy:

- Idiopathic. Develops against the background of absence of changes in the central nervous system. It is caused by genetically determined membrane and channelopathies, disorders of the maturation of the cerebral cortex. This pathology is benign. These are Panagiotopoulos syndrome, Rolandic epilepsy, Gastaut childhood occipital epilepsy and infantile episyndromes.

- Sympathetic. It is characterized by the presence of a cause. Morphological changes in most cases are visualized on tomography.

- Cryptogenic. It is secondary in nature, but morphological changes are not detected by neuroimaging. Another name for this type of FE is probably sympathetic.

Characteristic symptoms

The leading symptom complex is represented by repeated partial epileptic paroxysms. It is divided into:

- Simple, i.e. without loss of consciousness. There are motor, sensory, somatosensory, autonomic, with mental disorders or with hallucinations. The hallucinatory component is represented by visual, auditory, olfactory or taste disturbances.

- Complex ones with loss of consciousness can be supplemented by automatisms. During an attack there is confusion.

In epi-attacks, secondary generalization is possible. It starts out as complex or simple focal. As arousal occurs, it diffuses to other parts of the cortex. The paroxysm takes on a clonic-tonic character. One patient may have attacks of different forms.

Symptomatic FE is accompanied by additional clinical manifestations. They correspond to the underlying brain lesion. Leads to mental retardation, cognitive impairment, and decreased intelligence in children. Idiopathic FE is benign. It is not characterized by neurological deficits and intellectual and mental disorders.

What is focal dystonia

Without going into details, dystonia is a disorder in the “brain signal – muscle effort” command system. There is no signal, but the muscles contract. Or there is a signal, but the muscle/muscle group does not obey. The disease is neurological.

Reasons... Various reasons. Sometimes genetic errors, but not inherited, but arising as a result of a random combination. Sometimes dystonia occurs as a result of other neurological diseases, such as cerebral palsy and Parkinson's disease. Sometimes dystonia can develop from systematic and prolonged overload of certain muscle groups, from damage due to frequent clamping of leading nerves.

Dystonia has nothing to do with mental illness, mental development or memory. This is a violation of muscle activity. For example, the muscles around the eyes may contract on their own, or the muscles of the arms may contract spasmodically, or when swallowing, the muscles refuse to obey. Any muscle or muscle group can be affected.

Hand dystonia is notorious among musicians. It occurs as a result of compression of the central nerve in the area of the hand, or the ulnar nerve in the area of the elbow. Pianists and typists have to deal with spasms of one or more fingers. For many people, the development of focal dystonia is the end of their career, because it is much easier to develop it than to cure it. If we can talk about treatment at all, it is rather about alleviating the symptoms of manifestation, because neurological damage itself either does not recover, or recovers extremely slowly, or only partially.

It is better, of course, to capture the development of focal dystonia at the very beginning. The signal that a nerve in the area of the hand is caught in a clamp is pain and/or a feeling of numbness in the thumb, middle and index fingers. At first, the feeling of numbness appears only at night. “My hand goes numb” is serious. However, sometimes the pain does not radiate to the fingers or hand, but to the neck.

If the ulnar nerve is in the clamp, then the feeling of numbness occurs on the ring finger and little finger. The tricky thing about focal dystonia is that most likely there will be no pain. What will happen is a state of “everything falls out of hand” - in the literal sense of the word, because this dystonia weakens the functioning of the muscles of the palms.

The list goes on and on, from damage to the lateral nerves of the fingers to compressor neuropathy in the knee area - for example, in classical guitarists.

Dystonia is best diagnosed by electroneurography (ENMG).

The best treatment is to prevent the onset of the disease, to the extent possible. If problems have already begun, then you cannot delay treatment. At the very beginning of the disease, it is treated mainly physiotherapeutically and pedagogically - by straightening working postures/working methods. And if a clamp occurs, the nerve is released by surgery. The less damage the muscles received after pinching the nerve, the better the result of the operation. The lucky ones can get rid of the problem forever.

Uncontrolled muscle activity is treated with local botulinum injections. Unfortunately, strictly speaking, this is not a treatment, but a relief of symptoms - one injection lasts only 3 months. In 3% of patients, the body even begins to produce antibodies that block the action of botulinum.

For spasmodic dystonia, medications that relax muscles and beta inhibitors (for tremors) are sometimes used.

The better condition the muscles are, the less chance that overwork will lead to damage. Stretching exercises such as yoga are the best that a person whose work involves fatigue of certain muscle groups and nerve endings can practice. Heavy physical activity is a little different, you should also be careful with it.

If you sit at a computer most of the time, look for help to prevent muscle strain. Take breaks, keep your body flexible, alternate work with something else. Don't overstrain your eyes. A good physiotherapist will help you correctly create a load schedule, create a set of exercises, and even advise which devices are right for you.

Engage in a sport that is fashionable in these times - Nordic walking, which helps with muscle tension better than all other sports.

Our specialists are ready to help you:

| Osteopath | Structural, visceral and craniosarcle osteopathy, Su-Jok therapy, reflexology. |

| Masseur | Therapeutic, relaxing, myofascial, cupping, rolling, PIR massage. |

| Psychologist | Individual counseling, body-oriented gymnastics |

| Surgeon | Botulinum therapy |

Clinical picture depending on location

- Parietal. This is the rarest variant of epi-focus localization. Damage occurs with cortical dysplasia and tumors. Accompanied by simple somatosensory paroxysms. At the end of the attack, Todd's palsy or short-term aphasia may occur. If the focus of excitation is in the postcentral gyrus, Jacksonian seizures occur.

- Paroxysms in the occipital lobe are accompanied by visual impairment. Most often these are visual hallucinations lasting up to 13 minutes. Possible: narrowing of visual fields, transient amaurosis, illusions, hiccup blinking.

- A lesion in the frontal lobe causes short-term stereotypic paroxysms. They tend to be serial. No aura is noted. Unusual motor phenomena are characteristic: pedaling, complex automatic gestures, turning the head and eyes. Accompanied by emotional symptoms - agitation, screaming, aggression. Localization in the pericentral gyrus gives rise to Jacksonian epilepsy with movement disorders. In most patients, attacks occur during sleep.

- The temporal lobe is the most common location of the epileptogenic focus. Characterized by sensorimotor seizures with loss of consciousness, aura and automatism. The duration of the attack is on average 30-60 minutes. Children are characterized by oral automatisms, while adults - gestural ones. In 50% of cases, epileptic seizures have secondary generalization. If the dominant hemisphere is affected, post-ictal aphasia occurs.

Diagnostics

A patient with a first-time partial attack should be carefully examined. It is necessary to exclude cerebral pathologies: vascular malformations, tumors, cortical dysplasia. The neurologist collects anamnesis. Finds out the frequency, sequence, duration of an epileptic attack. Clarifies the neurological status. With the symptomatic nature of FE, it helps to establish the approximate localization of the source of excitation.

Instrumental diagnostics include:

- Electroencephalography. This form of epilepsy is recorded even during the interictal period. If the information content of a regular EEG is low, an examination with provocative tests and testing at the time of an attack is indicated.

- Subdural corticography allows you to establish the exact localization of the affected area.

- MRI helps to identify the morphological substrate. To diagnose the slightest structural changes, a minimum thickness of sections is required. With symptomatic FE, it is possible to establish the underlying disease and note dysplastic transformations. If there are no abnormalities during magnetic resonance imaging, cryptogenic or idiopathic focal epilepsy is diagnosed.

- PET of the brain helps to identify the area of hypometabolism in cerebral tissue corresponding to the lesion.

- Area SPECT examines the area of hyperdiffusion during attacks and hypoperfusion in the interictal period.

Therapy

A neurologist or epileptologist should prescribe treatment for the disease. The therapy is long-term and requires constant use of anticonvulsants. These are drugs valproic acid, carbamazepine, topiramate, phenobarbital, levetiracetam. If FE is symptomatic, the main thing is to eliminate the root cause. Taking medications is most effective for parietal and occipital epilepsy. When the pathology is localized in the temporal regions, after 1-2 goals the patient develops resistance to anticonvulsants. If conservative treatment does not bring results, the question of surgery may arise. They are performed by neurosurgeons. There are several intervention options:

- Resection of the epileptogenic area. It is advisable to operate on the patient only if FE is well localized.

- Removal of focal formation. These may be malformations, cysts or tumors.

- Extended resection is indicated if individual cells adjacent to the epileptogenic area also become a source of epi-activity.

To clarify the individual structure of the cortex, corticography is performed.

Medical prognosis

The prognosis of the disease depends primarily on its type. In symptomatic epilepsy, cerebral disorders have the greatest impact. If there are severe brain malformations and tumors, the prognosis is threatening. This type of epilepsy in children is complicated by mental retardation. Its severity depends on the age at which the disease debuted. With idiopathic PE, the prognosis is favorable. In most cases, it occurs without the appearance of cognitive pathologies. Spontaneous cessation of paroxysms in adolescence is possible.

With surgical intervention, in 60-70% of patients, epileptic seizures disappear or occur much less frequently. In the long-term period, stable remission is possible in 30% of patients.

Long-term successful therapy of focal epilepsy (based on a clinical case)

O.V. ANDREEVA

, Ph.D.,

P.N.

VLASOV , Doctor of Medical Sciences, Professor,

Clinic of Headache and Autonomic Disorders of Academician Alexander Vein, Department of Nervous Diseases, Faculty of Medicine, Moscow State Medical and Dental University.

A.I. Evdokimova The article is devoted to the problem of choosing an effective antiepileptic drug. The most common manifestations of epilepsy are considered, a clinical case of successful treatment of cryptogenic focal epilepsy with complex partial seizures using a classic antiepileptic drug is described.

Recently, due to the expansion of the arsenal of antiepileptic drugs (AEDs) for the successful treatment of partial seizures, a completely new problem has arisen - the problem of drug selection, which is an important component of the effective treatment of epilepsy.

In this regard, recommendations for the treatment of epileptic syndromes are constantly updated and the place of classical AEDs is reviewed. The latest generation of drugs are obtained, as a rule, by targeted synthesis or improvement of an existing molecule, due to which the properties of AEDs are improved or new ones appear. The antiepileptic properties of drugs, which doctors have been successfully using for several decades, were discovered by accident. They did not undergo the now generally accepted 4 phase studies before the widespread clinical introduction of AEDs, however, they are all well studied (millions of patients were treated) and are characterized by effectiveness comparable to the “new” and “newest” AEDs [2]. According to PEP companies, the advantages of these drugs are better tolerability, linear pharmacokinetics, lack of enzyme induction and other properties. At the same time, any AED, both classic and “new,” has its own therapeutic niche and side properties [1].

This article discusses the most common manifestations of epilepsy, namely partial seizures, with an example of a clinical case of successful therapy with classical antiepileptic drugs.

Below we present a very indicative long-term (from 1995 to the present) clinical observation of the effective use of the drug Pagluferal for the relief of complex partial seizures of epilepsy. Pagluferal was developed based on the prescription of the famous Russian psychiatrist M.Ya. Sereysky, called the Sereysky mixture. The launch of industrial production of the drug was initiated due to the popularity of this prescription among neurologists and its wide distribution in industrial pharmacies.

The effectiveness of the antiepileptic drug Pagluferal is due to the properties of the components included in its composition.

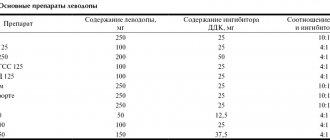

Table 1 shows the three existing dosages of the drug.

| Table 1. Composition of the antiepileptic drug Pagluferal | |||

| Pagluferal®-1 | Pagluferal®-2 | Pagluferal®-3 | |

| Composition per tablet | |||

| Phenobarbital | 25 mg | 35 mg | 50 mg |

| Calcium gluconate | 250 mg | 250 mg | 250mg |

| Caffeine sodium benzoate | 7.5 mg | 7.5 mg | 10 mg |

| Bromized | 100 mg | 100 mg | 150 mg |

| Papaverine hydrochloride | 15 mg | 15 mg | 20 mg |

Phenobarbital (5-ethyl-5-phenylbarbituric acid) is a derivative of barbituric acid, has a strong anticonvulsant, hypnotic, antispasmodic and sedative effect.

The mechanism of action of phenobarbital is multiple and is primarily associated with increased GABAergic inhibition mediated by postsynaptic chloride current receptors—the opening of chloride channels. (An increase in the content of chlorine ions inside neurons entails hyperpolarization of the cell membrane and reduces its excitability.) It has been shown that at therapeutic concentrations it enhances GABAergic transmission and inhibits glutamatergic neurotransmission, especially mediated by glutamate alpha-amino-5-methylisoxazole-4-propionate (AMPA )-receptors. In high concentrations, it affects the flow of sodium ions and blocks the flow of calcium ions through cell membranes (L- and N-type channels) [1, 3, 5, 7, 10].

The effectiveness of phenobarbital, which is part of the drug Pagluferal, is described in the Italian study FIRST (1997), which studied the effect of treatment of the first and second generalized seizure on long-term prognosis. The study found that the majority of physicians preferred FB (47% after the first seizure and 39% after the second seizure) as initial therapy for their patients compared with carbamazepine, valproate, or phenytoin [11]. It is important to note that the drug is included in the list of essential medicines of the World Health Organization [13], as well as in the List of vital and essential medicines, approved by Decree of the Government of the Russian Federation dated December 7, 2011 No. 2199-r [4]. In the latest recommendations for prescribing first monotherapy according to the type of seizure or epileptic syndrome ILAE (2013), FB is classified as category “C” for focal and primary generalized seizures in both children and adults [8]. Pharmacokinetic studies indicate greater clinical effectiveness of FB when used in combination drugs (Gluferal, Pagluferal) [9].

Calcium gluconate. The calcium gluconate contained in the drug Pagluferal plays an important role, replenishing the deficiency of calcium ions necessary for the process of transmitting nerve impulses, activating the action of enzymes involved in the synthesis of neurotransmitters. Lack of calcium in the body leads to seizures.

Caffeine-sodium benzoate (caffeine) - being a psychostimulant, increases reflex excitability of the spinal cord, stimulates the respiratory and vasomotor centers, stimulates metabolic processes in organs and tissues. The main feature of the use of caffeine in the drug is the stimulation of metabolic processes in muscle tissue and the central nervous system, which is important in the treatment of epileptic seizures.

Papaverine hydrochloride is an antispasmodic agent with myotropic action that has a hypotensive effect. Reduces tone and relaxes smooth muscles of internal organs and blood vessels.

Bromisal - depressing the central nervous system, has a sedative and moderate hypnotic effect. Strengthens inhibition processes and promotes their concentration. Well tolerated.

Clinical case

Patient E.I. 43 years old. She first came to the clinic in 1995 with complaints of recurring (with a frequency of 3-4 times a month) complex partial seizures, during which consciousness is lost. The attack is manifested by phonation in the form of mooing, growling, lasting up to 20-30 s, without falling, any accompanying motor automatisms, without tongue biting and involuntary urination.

From the anamnesis of the disease and life it is known: heredity for epilepsy is not burdened, the mother at birth was 25 years old from her first pregnancy, which occurred in the 3rd trimester with an increase in blood pressure, for which outpatient therapy was carried out; the first physiological term birth, which proceeded without complications; early perinatal period - without features. At the age of 1.7 years (early 1970s), for the first time in my life, a single febrile seizure occurred; at 3 years, during daytime sleep, there was a generalized convulsive seizure, with vomiting and tongue biting. The patient was treated with Sereysky mixture powder, during which no seizures were recorded. At the age of 12 years, the Sereysky mixture was replaced with the drug Pagluferal-3, which the patient regularly took 1 tablet at night. Despite the fact that no attacks were recorded for more than 15 years, the drug was not discontinued. From the age of 17, complex partial seizures of the described nature began to bother me with a frequency of up to 1-2 times a year, with a subsequent increase (up to 3-4 times a month) by the time of treatment, she took Pagluferal-3 (50 mg/day).

The allergic history is unremarkable.

Somatically: chronic gastritis.

Mental development corresponds to age and education, there are no complaints about memory loss (the patient studies at the Institute of Economics, and additionally takes German language courses).

Neurological status: signs of parasympathetic vegetative dystonia are revealed in the form of mild acrohyperhidrosis, without cerebral and focal neurological symptoms.

EEG: upon repeated examinations - a hypersynchronous variant with the distribution of the alpha rhythm to the anterior leads, rare discharges of a sharp wave - a slow wave in the frontal-anterior temporal leads; in one of the EEGs there is asymmetry due to an increase in the amplitude of discharges: a sharp wave - a slow wave on the right.

Fundus: no pathology.

MRI: slight expansion of the subarachnoid spaces in the frontal areas. No focal structural changes in the brain substance were detected.

The patient was diagnosed with cryptogenic focal epilepsy with complex partial waking seizures of high frequency, without personality changes.

Due to relapse and increased frequency of attacks, it was decided to replace Pagluferal-3 with carbamazepine with controlled release of the active substance and gradually increasing the dose to 600 mg/day. After 3 weeks At a dose of carbamazepine 400 mg/day, the patient complained of periodic short-term episodes of dizziness and the appearance of a maculopapular rash on the anterior surface of the chest and on the anterior surface of the forearms. Carbamazepine was discontinued and replaced with sodium valproate up to 500 mg/day, the attacks stopped, but the patient began to be bothered by almost constant severe gastralgia, which did not go away for more than 1 month. and causing significant inconvenience to the patient, because she was studying at a university and these unpleasant sensations did not allow her to concentrate on studying. After discussion with the patient, it was decided to return to Pagluferal therapy with a gradual increase in the daily dose to 75, and subsequently to 100 mg/day. At a dose of Pagluferal-3 (100 mg - 2 tablets at night), attacks have not been recorded for more than 10 years. The patient categorically refused repeated proposals to try to stop the antiepileptic drug.

EEG (in dynamics): slight disorganization in the background recording, no regional epileptiform changes were detected.

Concentration of phenobarbital in blood plasma at a drug dose of 100 mg/day: C min (before taking the drug) = 16.3 mcg/ml. The treatment is well tolerated: the patient does not feel any signs of taking the drug. Clinical and biochemical blood tests without clinically significant abnormalities.

Ultrasound of the heart and abdominal organs: without pathology.

It is currently known that the patient is engaged in a family business, graduated from two universities, and has two healthy children.

The presented clinical case is very indicative in terms of the high effectiveness of the drug Pagluferal (the current drug remission lasts more than 25 years), excellent tolerability (the patient graduated from two universities, speaks two foreign languages well, has two healthy children) and long follow-up (more than 30 years). The absence of deviations in the somatic status, clinical and biochemical blood tests indicates the absence of a cumulative toxic effect of the drug. Twice attempts to switch the patient to carbamazepine and sodium valproate ended in failure due to side effects of therapy: in the first case, when carbamazepine was administered, a rash appeared, and skin manifestations are fraught with serious complications, including the development of exfoliative dermatitis; in the second case, the prescription of sodium valproate was accompanied by prolonged gastralgia, which significantly reduced the patient’s quality of life. The availability and high effectiveness of Pagluferal are important factors in choosing a drug.

Thus, using the example of the given successful clinical case, it is shown that the drug Pagluferal is highly effective and indispensable in clinical practice in the treatment of certain categories of patients. The active ingredients included in its composition have a synergistic effect, positively influencing metabolic processes in the central nervous system and muscle tissue.

At present, when new anticonvulsants are being actively developed and introduced into clinical practice, Pagluferal retains its position in the therapeutic arsenal, since it meets the requirement of breadth of action—target [1, 2] that an antiepileptic drug must have. This can be explained by the strengths of the drug - a wide spectrum of action, a long half-life (the ability to take the drug once or twice a day), high efficiency and good tolerability at a low cost of treatment.

Literature

1. Karlov V.A.

Strategy and tactics of epilepsy treatment today. Journal neurol and psychiatrist. them. S.S. Korsakova, 2004, 104, 8: 28-34. 2. Karlov V.A., Karlov V.A. Epilepsy in children and adults, women and men. M.: Medicine, 2010: 577-606. 3. Mashkovsky M.D. Medicines: a manual for doctors. 1993, 1: 36-38. 4. Order of the Government of the Russian Federation of December 7, 2011 No. 2199-r, Moscow. Russian newspaper. 2011, No. 5660. 5. Register of Medicines of Russia. 2007: 921-922 6. Arankumar G, Morris H. Epilepsy update: new medical and surgical treatment options. Cleveland Clin J Med 1998, 65:527-37. 7. Brodie MJ, Dichter MA. Antiepileptic drugs. N Engl J Med 1996, 334: 168-75. 8. Glauser T, Ben-Menachem E, Bourgeois B et al. Updated ILAE evidence review of antiepileptic drug efficacy and effectiveness as initial monotherapy for epileptic seizures and syndromes. Epilepsia, 2013, 54(3): 551–563. 9. Pharmacokinetic effectiveness of phenobarbital in children with epilepsy. Mater. 2nd Int. scientific-practical conf. "Unconventional methods of treatment in pediatrics." Dubna, 1993: 169. 10. Hauptmann A. Luminal bei Epilepsie. Munch Med Wochenschr. 1912, 59: 1907-9. 11. Kwan PM. Brodie Phenobarbital for the treatment of epilepsy in the 21st century: clinical review. Epilepsia, 2004, 45(9): 1141-1149. 12. Musicco M, Beghi E, Solari A et al. Treatment of first tonic-clonic seizure does not improve the prognosis of epilepsy. Neurology, 1997, 49: 991-998. 13. Vlasov PN, Petrukhin VA, Karlov VA et al. Antiepileptic Drug Therapy During Pregnancy in Moscow Region: Comparing of 1998 and 2013 years. Epilepsia, 2014, 55 (2): 130, doi: 10.1111/epi.12675. 14. WHO Model List of Essential Medicines, 16th list (pdf). WHO, 2009. Source: Medical Council, No. 17, 2014