Mental and nervous diseases are quite common in people. The appearance of the first signs of these diseases causes confusion and stress for the patients themselves and their loved ones. In a state of fright, they do not immediately understand which doctor to contact. Our Leto clinic employs specialists who provide all types of psychoneurological assistance to people in need. Clients with Jacksonian epilepsy also come to us. This is the name of one of the variants of a group of diseases that occur with their own specific convulsive manifestations. If signs of illness or other problems appear, call us at: 8(969)060-93-93 . Our consultants will tell you what and how to do.

What is Jackson's epilepsy?

This pathology refers to a neurological disorder with its characteristic convulsions and sensory disturbances without loss of consciousness. Symptoms spread in a certain order. A variant of these epileptic disorders is not common, but has a characteristic clinical picture, without causing any particular difficulties for the doctor in diagnosis.

Jacksonian epilepsy is a manifestation of the focal form of the disease. The epileptiform focus is formed as a local zone in the area of the pre/postcentral gyrus of the brain. A detailed description of the symptoms was carried out by the French doctor Bravais and the English doctor Jackson, from whose name the name of the disease variant came. He was the first to identify the localization of a structural painful focus.

general information

Jacksonian epilepsy is a type of focal epilepsy, during which the anomaly manifests itself in the cortex of the pre- and / or postcentral gyrus and is usually of a local type, but in some cases it can develop causing secondary generalization of a fatal seizure. The study of this phenomenon began in the distant 19th century; multiple experiments were carried out by Dr. Bravais from France, as well as by the Englishman J. Jackson, specializing in the field of neurology. As a result of the scientific research of the second scientist, this disease acquired its name.

The presented deviation from the norm appears as a result of a cerebral anomaly of an organic nature, that is, with the formation of inflammation, benign or malignant formations, vascular aneurysms, and other things. At any age, the occurrence of such a process indicates damage to the brain.

Causes of the disease

During the survey and diagnosis, psychiatrists at our clinic identify various causal factors leading to the development of this disease.

Patients are diagnosed with:

Previous or currently existing infectious and inflammatory pathologies: arachnoiditis, encephalitis, meningitis.- Abscesses, tumor processes in brain tissue.

- Aneurysms of cerebral vessels.

- Parasitic lesions: cysticercosis, echinococcosis.

- Traumatic brain injuries.

- Vascular anomalies.

- Hereditary predisposition.

In childhood, pathology is provoked by:

- Fetal hypoxia.

- Transfer of intrauterine infections.

- Birth injury.

Forecast

In essence, Jackson's epilepsy cannot be classified as a dangerous and life-threatening disease; rather, it is an unpleasant and disturbing little thing when compared with ordinary epilepsy, accompanied by impaired consciousness and loss of certain body functions.

The prognosis for this disease is very comforting, it can be treated well, and with timely contact with a specialist, the number of seizures can be significantly reduced.

The cause of this form of the disease can be a variety of diseases associated with inflammatory processes in the brain or heredity.

The disease is treatable, but only on condition that the patient is ready to follow the path to recovery for at least a year. The main sign of the presence of the disease is considered to be cramps in various parts of the body - usually in the arms or legs, less often in the face.

Characteristic complaints and symptoms

Jacksonian epilepsy syndrome consists of a variety of manifestations. Paroxysmal seizures differ from the classic version. Doctors at our medical center always identify the typical pathological complex characteristic of this disease.

The most characteristic feature of an attack is the local appearance of convulsive twitching. Most often, trembling or unpleasant sensations (paresthesia, lack of sensitivity) are formed in the face, hand, and fingers. Next, the paroxysmal reaction goes to the shoulder area, then to the leg from the hip to the foot. This sign is called the “Jacksonian march” in medicine. Less commonly, paroxysm comes from the toes, then to the arm and face.

Another type occurs only in the focus of occurrence without spreading. With the classic version of Jacksonian epilepsy, the patient rarely loses consciousness. Sometimes complicated episodes are observed, including status epilepticus, which consists of alternating attacks one after another.

The following processes are distinguished by complexity:

Simple seizures. In this case, convulsions and paresthesias always begin from the same place. The patient can stop their spread by fixing the painful area with his hand.- Complicated paroxysms. Convulsive areas with altered sensitivity progressively spread to different muscles. It becomes impossible to stop their development.

- Complicated with consequences. After an attack, the patient develops paresis of the painful limb. Over time it goes away. This clinical variant alarms the doctor in terms of oncological processes.

Pathological paroxysms are accompanied by additional neurological symptoms characteristic of the main causative disease.

Symptoms

This type of anomaly has multiple symptoms. The main common feature of all processes is the formation of a tumor in a specific area, often on the upper limbs and facial area, and its further progression throughout the body.

“Motor Jackson” can appear when the cortex of the precentral part of the epileptogenic plane is excited. This form is distinguished by cramps that begin in the muscle tissue of the thumb on the hand, growing to the entire limb, face and legs. In special cases, cramps may start from the first toe on the lower extremity and move upward to the entire structure of the leg, arm and facial area. Such attacks are clinically significant with an early, brief tonic phase. Seizures can end abruptly, but usually occur in the reverse order.

“Sensory Jackson” - manifests itself when the cortex of the postcentral gyrus is activated, is characterized by similar motor activity progression, but is associated with sensitivity disorders. At certain points, the disease occurs in a limited area of its occurrence and cannot spread to other areas. The described phenomenon in modern medicine is called simple Jacksonian paroxysm.

Also, the disease manifests itself with the following symptoms:

- Loss of consciousness (some moments of convulsions occur without loss of consciousness and are localized only at one point).

- The appearance of paresis of the limbs.

- Increased duration and severity of seizures.

- In rare cases, paralysis begins.

Diagnostics

In our clinic, the diagnosis is established based on a comprehensive examination.

It includes:

- Questioning the patient to identify characteristic complaints characteristic of the disease.

- Determining the causative disease causing the attacks.

- Diagnosis of psychoneurological status.

- General examination and physical examination, including measurement of A/D, pulse, auscultation of the respiratory and cardiac organs, palpation of the abdomen.

When Jacksonian epilepsy is detected, a differential diagnosis must be carried out, excluding a number of pathologies that give similar symptoms.

The doctor checks the patient for the presence or absence of:

Myoclonic epileptiform seizures.- Hysterical neurosis.

- Paroxysms of unknown origin.

To eliminate mistakes, our doctors often use the consultation method, inviting an epileptologist and a neurologist.

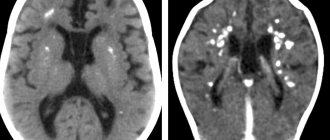

Encephalogram data should be taken into account in the diagnostic process. Stimuli are used to identify indicators of epileptic activity in the form of focal cortical discharges. Clients are given light and sound signals, to which the body reacts with peak activity. In some situations, long-term video monitoring is required.

An informative picture is provided by computed tomography and MRI of the brain. With their help, tumors, cystic formations, signs of inflammation, and abscesses are identified.

Jacksonian seizures

Jacksonian epilepsy is accompanied by seizures, the characteristic feature of which is that the person is of sound mind and memory, or rather, consciousness.

Each seizure has its own characteristics, but many patients who have suffered from this form of epilepsy since childhood have learned to cope with them quite well without resorting to medical help.

The first seizures begin in the anterior part of the brain, from where they impulsely move to the affected part of the body. A spasm that engulfs a finger of the left hand can be located only there, or it can affect the same finger on the right hand.

Thus, the seizure does not spread to the entire arm as a whole, but is transferred to the same part of the body, but in a parallel area .

A feature of the seizure is also considered to be the fact that convulsions, once affecting the right leg, will occur in it again and again with a frequency of seconds, minutes, hours and days.

To reduce the intensity of convulsive muscle contractions, you can stop the affected area, preventing their further spread.

Cupping the leg can be done by squeezing it tightly with both hands, or with a light but firm massage. The same actions should be taken if the spasm affects any other part of the body.

The following types of seizures are distinguished:

- Jacksonian march - a series of seizures following one after another, the interval between which is extremely small;

- a seizure affecting the facial muscles;

- a seizure that is located in the muscles of a separate part of the body.

What is needed to cure Jacksonian epilepsy

If you suspect the appearance of this pathology, you should undergo an examination by a specialist at our Leto mental health center. Hotline phone number: 8(969)060-93-93 . The call center is open 24 hours a day. Call us and the consultant on duty will give comprehensive answers to all your questions. The anonymity of the appeal allows you to talk about existing problems completely calmly. 24-hour consultation gives you the opportunity to make calls at any time convenient for you.

You can make an appointment with a doctor by telephone, and, if necessary, call a specialist to your home. If you need to transport a patient, we will provide conditions for a comfortable transfer.

In the inpatient department of the clinic, you can choose the most suitable ward for your stay.

We offer options:

- Standard (2-3-4 seats).

- Comfort for two people.

- VIP – for a stay of one person.

Attentive and qualified staff will monitor the patient around the clock.

Treatment approach

It is difficult to treat the disease, since all efforts of doctors in this case should be aimed at eliminating not the symptoms, but the disease itself.

Typically, the course of treatment lasts at least a year, during which the patient is prescribed the following anticonvulsants: lamictal, benzonal, phenobarbital, diphenine and hexamide.

As well as medications that contain valproic acid. They also try to treat the disease by providing a stimulating effect on the vagus nerve.

The patient may be prescribed absorbent agents, dehydration and restorative drugs.

If none of the above medications have the desired effect, the patient may be advised to consult a neurosurgeon to identify hidden causes of the disease.

Cost of services

| CONSULTATIONS OF SPECIALISTS | |

| Initial consultation with a psychiatrist (60 min.) | 6,000 rub. |

| Repeated consultation | 5,000 rub. |

| Consultation with a psychiatrist-narcologist (60 min.) | 5,000 rub. |

| Consultation with a psychologist | 3,500 rub. |

| Consultation with Gromova E.V. (50 minutes) | 12,000 rub. |

| PSYCHOTHERAPY | |

| Psychotherapy (session) | 7,000 rub. |

| Psychotherapy (5 sessions) | 30,000 rub. |

| Psychotherapy (10 sessions) | 60,000 rub. |

| Group psychotherapy (3-7 people) | 3,500 rub. |

| Psychotherapy session with E.V. Gromova (50 minutes) | 12,000 rub. |

| TREATMENT IN A HOSPITAL | |

| Ward for 4 persons | 10,000 rub./day |

| Ward for 3 persons | 13,000 rub./day |

| Ward 1 bed VIP | 23,000 rub./day |

| Individual post | 5,000 rub. |

| PETE | 15,000 rub./day |

This list does not contain all prices for services provided by our clinic. The full price list can be found on the “Prices” , or by calling: 8(969)060-93-93. Initial consultation is FREE!

Epilepsy in childhood

Part 2. Read the beginning of the article in No. 6, 2014

Epilepsy is manifested by repeated unprovoked seizures, which are of a variety of sudden and transient pathological phenomena affecting consciousness, motor and sensory spheres, the autonomic nervous system, as well as the patient’s psyche. Two attacks occurring in a patient within 24 hours are considered a single event [1].

Clinical manifestations of epilepsy are variable and diverse. They mainly depend on both the form of the disease and the age of the patients. Age-related aspects of epilepsy in pediatric neurology suggest the need to clearly distinguish age-dependent forms of this group of diseases [1, 2].

Clinical manifestations of epilepsy in children and adolescents

The clinical picture of epilepsy includes two periods: paroxysmal and interictal (interictal). Manifestations of the disease are determined by the type of seizures the patient has and the location of the epileptogenic focus. In the interictal period, the patient may be completely absent of neurological symptoms. In other cases, neurological symptoms in children may be due to a disease causing epilepsy [1, 3].

Partial seizures

The manifestations of simple partial seizures depend on the location of the epileptogenic focus (frontal, temporal, parietal, occipital lobes, perirolandic region, etc.). Up to 60–80% of epileptic seizures in children and adult patients are partial. These attacks occur in children with various phenomena: motor (tonic or clonic convulsions in the upper or lower extremities, on the face - contralateral to the existing focus), somatosensory (a feeling of numbness or “current passing” in the limbs or half of the face opposite to the epileptogenic focus), specific sensory (simple hallucinations - acoustic and/or visual), vegetative (mydriasis, sweating, pallor or hyperemia of the skin, discomfort in the epigastric region, etc.) and mental (transient speech disorders, etc.) [1, 4].

Clinical manifestations of partial seizures are markers of the topic of the epileptic focus. When the lesions are localized in the motor cortex, seizures are usually characterized by focal tonic and clonic convulsions—Jacksonian-type motor seizures. Sensory Jacksonian seizures (focal paresthesias) occur in the presence of an epileptic focus in the posterior central gyrus. Visual seizures (simple partial), characterized by corresponding phenomena (sparks of light, zigzags in front of the eyes, etc.), occur when epileptic foci are located in the occipital cortex. Various olfactory (unpleasant odor), acoustic (tinnitus sensation) or gustatory (unpleasant taste) phenomena occur when the lesions are localized, respectively, in the olfactory, auditory or gustatory cortex. Lesions located in the premotor cortex induce adversive seizures (a combination of abduction of the eyeballs and head followed by clonic jerks); Often such attacks transform into secondary generalized ones. Partial seizures can be simple or complex [1, 3].

Simple partial seizures (SPS). Manifestations depend on the localization of the epileptic focus (localization-related). PPPs are motor and occur without change or loss of consciousness, so the child is able to talk about his feelings (except for those cases when attacks occur during sleep) [1].

PPP is characterized by the occurrence of seizures in one of the upper limbs or in the face. These seizures lead to deviation of the head and aversion of the eyes towards the hemisphere contralateral to the localization of the epileptic focus. Focal seizures may begin in a limited area or become generalized, resembling secondary generalized tonic-clonic seizures. Todd's paralysis (or paresis), expressed in transient weakness for several minutes to several hours, as well as abduction of the eyeballs towards the affected hemisphere, indicate an epileptogenic focus. These phenomena appear in the patient after PPP (postictal period) [1, 4].

Simple partial vegetative seizures (SPVP). It is proposed to separately distinguish this type of relatively rare epileptic seizures. PPVPs are induced by epileptogenic foci localized in the orbito-insulo-temporal region. In PPVP, autonomic symptoms predominate (sweating, sudden palpitations, abdominal discomfort, rumbling in the abdomen, etc.). Autonomic manifestations in epilepsy are quite diverse and are determined by digestive, cardiac, respiratory, pupillary and some other symptoms. Abdominal and epigastric epileptic seizures are considered more typical for children aged 3 to 7 years, while cardiac and pharyngeal seizures are more common at older ages. Respiratory and pupillary PPVPs are characteristic of epilepsy in patients of any age. Thus, clinically, abdominal epileptic seizures are usually characterized by the occurrence of sharp pain in the abdominal area (sometimes in combination with vomiting). Epigastric PPVP manifests itself in the form of various signs of discomfort in the epigastric region (rumbling in the abdomen, nausea, vomiting, etc.). Cardiac epileptic seizures manifest themselves in the form of tachycardia, increased blood pressure, pain in the heart (“epileptic angina pectoris”). Pharyngooral PPVPs are epileptic paroxysms expressed in hypersalivation, often in combination with movements of the lips and/or tongue, swallowing, licking, chewing, etc. The main manifestation of pupillary PPVPs is the appearance of mydriasis (the so-called “pupillary epilepsy”). Respiratory PPVPs are characterized by attacks of respiratory distress—shortness of breath (“epileptic asthma”) [1].

Complex partial seizures (CPS). The manifestation of SPP is very diverse, but in all cases, patients experience changes in consciousness. It is quite difficult to detect disturbances of consciousness in infants and young children. The onset of SPP can be expressed as a simple partial seizure (SPS) followed by loss of consciousness; changes in consciousness can also occur directly during an attack. SSP often (in about half of the cases) begins with an epileptic aura (headache, dizziness, weakness, drowsiness, discomfort in the mouth, nausea, discomfort in the stomach, numbness of the lips, tongue or hands; transient aphasia, a feeling of constriction in the throat, difficulty breathing, auditory and/or olfactory paroxysms, unusual perception of everything around, sensations déjà vu (already experienced) or jamais vu (visible, heard and never experienced for the first time), etc.), which makes it possible to clarify the localization of the epileptogenic focus. Phenomena such as convulsive clonic movements, forced deviation of the head and eyes, focal tonic tension and/or various automatisms (repetitive motor non-purposeful activity: licking lips, swallowing or chewing movements, elaborate movements of fingers, hands and facial muscles, in those who have begun to walk - running etc.) may accompany SPP. Automated movements in SPP are not goal-directed; Contact with the patient is lost during an attack. In infancy and early childhood, the described automatisms are usually not expressed [1, 4].

Partial seizures with secondary generalization (PSG). Secondary generalized partial seizures are tonic, clonic, or tonic-clonic. PPVH always occurs with loss of consciousness. They can occur in children and adolescents after both simple and complex partial seizures. Patients may have an epileptic aura (about 75% of cases) preceding PPVH. The aura usually has an individual character and can be stereotypical, and depending on the damage to a particular area of the brain, it can be motor, sensory, autonomic, mental or speech [1, 4].

During PPVG, patients lose consciousness; they fall if they are not in a lying position. A fall is usually accompanied by a specific loud cry, which is explained by spasm of the glottis and convulsive contraction of the chest muscles [1].

Generalized seizures (primarily generalized)

Like partial (focal) epileptic seizures, generalized seizures in children are quite diverse, although they are somewhat more stereotypical.

Clonic seizures. They are expressed in the form of clonic convulsions, which begin with a sudden onset of hypotension or a short tonic spasm, followed by bilateral (but often asymmetrical) twitching, which can predominate in one limb [1, 4]. During an attack, differences in the amplitude and frequency of the described paroxysmal movements are noted. Clonic seizures are usually observed in newborns and infants and young children.

Tonic seizures. These convulsive seizures are expressed in a short-term contraction of the extensor muscles. Tonic seizures are characteristic of Lennox–Gastaut syndrome; they are also observed in other types of symptomatic epilepsies. Tonic seizures in children are more likely to occur during non-REM sleep than during wakefulness or REM sleep. With concomitant contraction of the respiratory muscles, tonic convulsions may be accompanied by the development of apnea [1].

Tonic-clonic seizures (TCS). Expressed in the form of convulsions of the grand mal type. TST is characterized by a tonic phase lasting less than 1 minute, accompanied by upward movement of the eyes. At the same time, a decrease in gas exchange occurs due to tonic contraction of the respiratory muscles, which is accompanied by the appearance of cyanosis. The clonic convulsive phase of the attack follows the tonic phase and is expressed in clonic twitching of the limbs (usually for 1–5 minutes); Gas exchange is improved or normalized. TST may be accompanied by hypersalivation, tachycardia, and metabolic and/or respiratory acidosis. With TST, the postictal state often lasts less than 1 hour [1, 4].

Absence seizures (absence seizures). They occur as a petit mal (“minor epileptic seizure”) and represent a short-term loss of consciousness followed by amnesia (“freezing”). Absence seizures may be accompanied by clonic twitching of the eyelids or limbs, dilated pupils (mydriasis), changes in muscle tone and skin color, tachycardia, piloerection (contraction of the muscles that raise the hair) and various motor automatisms [1, 3, 4].

Absence seizures can be simple or complex. Simple absence seizures are attacks of short-term loss of consciousness (with characteristic slow waves on the EEG). Complex absence seizures are disturbances of consciousness combined with atony, automatisms, muscle hypertonicity, myoclonus, coughing or sneezing attacks, as well as vasomotor reactions. It is also customary to distinguish subclinical absence seizures, that is, transient disorders without pronounced clinical manifestations, noted during a neuropsychological examination and accompanied by slow-wave activity during an EEG study [1].

Simple absence seizures are much less common than complex ones. If the patient has an aura, focal motor activity in the limbs and postictal weakness, freezing is not regarded as absence seizures (in such cases one should think of complex partial seizures) [1].

Pseudoabsences. This type of seizure is described by H. Gastaut (1954) and is difficult to distinguish from true absence seizures. With pseudo-absence seizures, a short-term loss of consciousness with a stoppage of gaze is also observed, but the beginning and end of the seizure are somewhat slowed down. Pseudo-absence attacks themselves are longer in duration and are often accompanied by paresthesia, the déjà vu phenomenon, severe autonomic disorders, and often postictal stupor. Pseudoabsences refer to partial (focal) temporal paroxysms. EEG study is of decisive importance in differentiating pseudo-absences from true absences [1, 3].

Myoclonic seizures (epileptic myoclonus). Myoclonic jerks can be isolated or recurrent. Myoclonus is characterized by short duration and rapid bilateral symmetrical muscle contractions, as well as the involvement of various muscle groups. Myoclonus is usually observed in children with benign or symptomatic forms of epilepsy. In the structure of the group of symptomatic epilepsies, myoclonus can be observed both in various non-progressive forms of the disease (Lennox-Gastaut syndrome, etc.), and in relatively rare progressive forms of myoclonus epilepsy (Lafora disease, Unferricht-Lundborg disease, MERRF syndrome, neuronal ceroid lipofuscinosis and etc.). Sometimes myoclonic activity is associated with atonic seizures; in this case, children can fall when walking [1, 4].

Atonic attacks. They are characterized by a sudden fall of a child who can stand and/or walk, that is, a so-called “drop-attack” is noted. During an atonic attack, there is a sudden and pronounced decrease in tone in the muscles of the limbs, neck and torso. During an atonic attack, the onset of which may be accompanied by myoclonus, the child’s consciousness is impaired. Atonic seizures are more often observed in children with symptomatic generalized epilepsy, but in primary generalized forms of the disease they are relatively rare [1, 3, 4].

Akinetic attacks. They resemble atonic seizures, but, unlike them, with akinetic seizures the child experiences sudden immobility without a significant decrease in muscle tone [1].

Thermopathological manifestations of epilepsy

Back in 1942, AM Hoffman and FW Pobirs suggested that attacks of excessive sweating were a form of “focal autonomic epilepsy.” H. Berger (1966) first described fever (hyperthermia) as an unusual manifestation of epilepsy, and subsequently DF Cohn et al. (1984) confirmed this thermopathological phenomenon, calling it “thermal epilepsy” [1, 5]. The possibility of manifestation of intermittent fever or “febrile cramps” in epilepsy was reported by S. Schmoigl and L. Hohenauer (1966), H. Doose et al. (1966, 1970), and K. M. Chan (1992).

TJ Wachtel et al. (1987) believe that generalized tonic-clonic seizures can lead to hyperthermia; in their observations, 40 out of 93 patients (43%) had a temperature rise above 37.8 °C at the time of the attack. JD Semel (1987) described complex partial status epilepticus, manifesting as “fever of unknown origin” [1].

In some cases, epilepsy can manifest itself in the form of hypothermia. RH Fox et al. (1973), DJ Thomas and ID Green (1973) described spontaneous intermittent hypothermia in diencephalic epilepsy, and MH Johnson and SN Jones (1985) observed status epilepticus with hypothermia and metabolic disturbances in a patient with agenesis of the corpus callosum. WR Shapiro and F. Blum (1969) described spontaneous recurrent hypothermia with hyperhidrosis (Shapiro syndrome). In the classic version, Shapiro syndrome is a combination of agenesis of the corpus callosum with paroxysmal hypothermia and hyperhidrosis (cold sweat), and is pathogenetically associated with the involvement of the hypothalamus and other structures of the limbic system in the pathological process. Various researchers refer to Shapiro's syndrome as "spontaneous intermittent hypothermia" or "episodic spontaneous hypothermia." A description of spontaneous periodic hypothermia and hyperhidrosis without corpus callosum agenesis is presented. K. Hirayama et al. (1994), and then KL Lin and HS Wang (2005) described “reversible Shapiro syndrome” (agenesis of the corpus callosum with periodic hyperthermia instead of hypothermia) [1, 6].

In most cases, paroxysmal hypothermia is considered to be associated with diencephalic epilepsy. Although, according to C. Bosacki et al. (2005), the hypothesis of “diencephalic epilepsy” in relation to episodic hypothermia is not convincing enough; the epileptic origin of at least some cases of Shapiro syndrome and similar conditions is confirmed by the fact that antiepileptic drugs prevent the development of attacks of hypothermia and hyperhidrosis [1, 3].

Hyperthermia or hypothermia cannot be clearly classified as focal or generalized paroxysms, but the very possibility of manifestation of epileptic seizures in children in the form of pronounced temperature reactions (isolated or in combination with other pathological phenomena) should not be ignored [1, 7].

Mental characteristics of children with epilepsy

Many mental changes in children and adolescents with epilepsy remain unnoticed by neurologists unless they reach significant severity. However, without this aspect, the picture of the clinical manifestations of the disease cannot be considered complete [3].

The main types of mental disorders in children with epilepsy, as numerous and varied as the paroxysmal manifestations of the disease, can be schematically classified into one of 4 categories: 1) asthenic conditions (neurotic reactions of the asthenic type); 2) mental development disorders (with varying severity of intellectual deficit); 3) deviant forms of behavior; 4) affective disorders [1, 8, 9, 11].

The most typical personality changes with a certain duration of epilepsy are considered to be the polarity of affect (a combination of affective viscosity, a tendency to “get stuck” on certain, especially negatively colored, affective experiences, on the one hand, and affective explosiveness, impulsivity with a large force of affective discharge, on the other) ; egocentrism with the concentration of all interests on one’s own needs and desires; accuracy, reaching the point of pedantry; exaggerated desire for order, hypochondria, a combination of rudeness and aggressiveness towards some with obsequiousness and subservience to others (for example, to elders on whom the patient depends) [1, 3, 8, 11].

In addition to this, children and adolescents with epilepsy are characterized by pathological changes in the sphere of instincts and drives (increased instinct of self-preservation, increased drives, which are associated with cruelty, aggressiveness, and sometimes increased sexuality), as well as temperament (slowing the pace of mental processes, the predominance of a gloomy mood). and gloomy mood) [1, 10].

Less specific in the picture of persistent personality changes in epilepsy are violations of intellectual-mnestic functions (slowness and rigidity of thinking - bradyphrenia, its perseverativeness, tendency to detail, decreased memory of the egocentric type, etc.); the described changes become more noticeable in children who have reached the age of starting school [1, 8, 11].

In general, among the mental disorders characteristic of epilepsy, the following disorders appear: receptor disorders, or sensopathy (senestopathies, hyperesthesia, hypoesthesia); perception disorders (hallucinations: visual, extracampal, auditory, gustatory, olfactory, tactile, visceral, hypnagogic and complex; pseudohallucinations); psychosensory disorders (derealization, depersonalization, changes in the speed of events over time); affective disorders (hyper- and hypothymia, euphoria, ecstatic states, dysphoria, parathymia, apathy; inadequacy, dissociation and polarity of affect; fears, affective exceptional state, affective instability, etc.); memory disorders or dysmnesia (anterograde, retrograde, anteroretrograde and fixation amnesia; paramnesia); attention disorders (attention disorders, narrowed attention); intellectual disorders (from delayed psychomotor development to dementia); motility disorders (hyper- and hypokinesia); speech disorders (motor, sensory or amnestic aphasia; dysarthria, oligophasia, bradyphasia, speech automatism, etc.); so-called “impulse disorders” (motivation): hyper- and hypobulia; desire disorders (anorexia, bulimia, obsessions); sleep disorders or dyssomnia (hypersomnia, hyposomnia); psychopathic-like disorders (characterological disturbance of emotional-volitional functions and behavior); various forms of disorientation (in time, environment and self) [1, 3, 8, 9–12].

Almost all of the disorders described above can lead to or be accompanied by certain disturbances of consciousness. Therefore, in “epileptic psychiatry” by A. I. Boldarev (2000), syndromes of changes in consciousness are primarily considered: syndrome of increased clarity of consciousness and syndromes of decreased clarity of consciousness (partial and generalized) [12].

Clarity syndrome (or hyper-wakefulness syndrome). It occurs quite often in epilepsy, although it remains poorly studied. The content of the syndrome of increased clarity of consciousness is determined as follows: clarity, vividness and distinctness of perception; quick orientation in the environment, instantaneousness and vividness of memories, ease of resolving the situation that has arisen, rapid flow of thought processes, sensitive responsiveness to everything that happens. It is believed that the syndrome of increased clarity of consciousness manifests itself most clearly during hyperthymia, as well as during hypomanic and ecstatic states [1, 12].

Syndromes of decreased clarity of consciousness are partial. In epilepsy, they are transitional states between preserved and deeply disturbed consciousness of the patient. They can occur in the pre-, inter- or post-attack periods and are quite diverse (decreased susceptibility of external stimuli and irritants, disturbances in their associative processing, inhibition of varying degrees of severity, transient decrease in intelligence, slowness of reactions and mental processes, decreased communication skills, dulling of emotions, narrowing attention span, impaired memory, as well as partial disorder of orientation in time, environment and self, etc.). A. I. Boldarev (2000) refers to “special states of consciousness” as psychosensory disorders and changes in perception over time (including the phenomena of déjà vu and jamais vu). In epilepsy, dreamy states are a common variant of partial disorder of consciousness (of the jamais vu or déjà vu type); their duration varies from a few seconds or minutes to several hours/days. Dream-like states are characteristic of temporal lobe epilepsy. Epileptic trances are an unmotivated and unreasonable movement of a patient from one place to another, occurring against the background of a partial disorder of consciousness and outwardly ordered behavior, as well as subsequent incomplete amnesia. Trances of varying duration (from several hours to several weeks) can be provoked by emotional stress and/or acute somatic pathology (ARD, etc.) [1, 12].

Generalized syndromes of decreased clarity of consciousness are relatively numerous. These include the following psychopathological phenomena: stupefaction (difficulty and slowdown in the formation/reproduction of associations); delirium (a disorder of consciousness, saturated with visual and/or auditory hallucinations followed by incomplete amnesia); oneiroid (a dream state in which dream-like events occur in a subjective unreal space, but are perceived as real); drowsy states (changes in consciousness and incomplete orientation in what is happening or lack of orientation and wakefulness after awakening); somnambulism (walking at night in a state of incomplete sleep); simple psychomotor seizures (short-term - a few seconds, single automatic actions with switching off consciousness) and complex psychomotor seizures (longer - up to 1 minute or more, attacks of automaticity with switching off consciousness, reminiscent of short-term twilight states); twilight states of consciousness (complete disorientation of the patient, affective tension, hallucinations, delusional interpretation of what is happening, agitation, inadequate and unmotivated behavior); amental states (profound disruption of orientation in the environment and one’s own personality, combined with the inability to form and reproduce associations; after the patient leaves the amentive state, complete amnesia is noted); soporous state (a deep disturbance of consciousness, from which the patient can be brought out for a short time by sharp irritation - short-term partial clearing of consciousness; when leaving the soporous state, anterograde amnesia is noted); coma (a deep unconscious state with a lack of response to external stimuli - the pupillary and corneal reflexes are not detected; after leaving the comatose state, anterograde amnesia occurs); undulating disorder of consciousness (intermittent fluctuations of consciousness - from clear to complete shutdown) [1, 12].

Other mental disorders in epilepsy that occur in childhood are represented by the following disorders: derealization syndrome (impaired spatial perception during attacks); syndromes of impaired perception in time (déjà vu, jamais vu, déjà entendu (already heard)); a syndrome of a combination of psychosensory disorders with a partial change in consciousness, a violation of perception in time and an ecstatic state (psychosensory disorders - depersonalization and derealization, including disturbances in the body diagram, an ecstatic state, the unreality of time, etc.); syndrome of psychosensory disorders and oneiric state (complex syndrome of gross derealization, depersonalization and oneiric); syndrome of uncertainty of subjective experiences (the inability to specify one’s own subjective sensations and experiences, sometimes with auditory or visual hallucinations); dissociation syndrome between objective and subjective experiences (the patient’s denial of the presence of multiform or abortive epileptic seizures, observed both at night and during the day); complex syndromes (complex attacks with a combination of various sensations, viscerovegetative manifestations, affective disorders and other symptoms); delusional syndromes (paranoid, paranoid or paraphrenic); catatonic substuporous state (incomplete immobility during prolonged and chronic epileptic psychoses, often combined with partial or complete mutism, muscle hypertonicity and symptoms of negativism); catatonic syndromes (catatonic excitement - impulsiveness, mannerisms, unnaturalness, motor agitation, or stupor - mutism, catalepsy, echolalia, echopraxia, stereotypy, grimacing, impulsive acts); Kandinsky–Clerambault syndrome or mental automatism syndrome (pseudohallucinations, mental automatisms, delusions of persecution and influence, a feeling of mastery and openness; 3 variants of mental automatism are possible: associative, kinesthetic and senestopathic); mental disinhibition syndrome or hyperkinetic syndrome (general disinhibition with rapidly changing movements, restlessness, inability to concentrate, increased distractibility, inconsistency in actions, violations of logical construction, disobedience) [1, 8, 12].

Cognitive impairment in epilepsy

Impaired cognitive functions occur in partial and generalized forms of epilepsy. The nature of cognitive “epileptic” deficit can be acquired, fluctuating, progressive, chronic and degrading (leading to the development of dementia) [1, 12].

T. Deonna and E. Roulet-Perez (2005) identify 5 groups of main factors that potentially explain cognitive (and behavioral) problems in children with epilepsy: 1) brain pathology (congenital or acquired); 2) epileptogenic damage; 3) epilepsy as the basis of electrophysiological dysfunction; 4) the influence of medications; 5) influence of psychological factors [13].

The structure of intelligence in patients with epilepsy is characterized by impaired perception, decreased concentration, the volume of short-term and working memory, motor activity, hand-eye coordination, constructive and heuristic thinking, speed of skill formation, etc., which causes difficulties in social integration in patients and education, reducing the quality of life. The negative impact on cognitive functions of the early onset of epilepsy, refractoriness to therapy, and toxic levels of antiepileptic drugs in the blood has been demonstrated by many researchers [1, 12, 14, 15].

Symptomatic epilepsy due to organic damage to the central nervous system is also a serious risk factor for cognitive impairment. Disturbances of higher mental functions in epilepsy depend on the location of the focus of epileptic activity and/or structural damage to the brain. With left-sided damage, children with frontal lobe epilepsy have deficits in decisiveness, verbal long-term memory, and difficulties in visual-spatial analysis. Their frequent attacks affect their level of attention and ability to inhibit impulsive responses; patients with the onset of epilepsy before the age of 6 years are not capable of constructing a behavioral strategy [1, 12, 14].

In generalized epilepsy, epileptiform changes in the EEG cause transient impairment of cognitive functions (extension of reaction time, etc.) [1, 12].

Severe impairments of cognitive functions are characteristic of epileptic encephalopathies of early childhood (early myoclonus encephalopathy, Ohtahara, West, Lennox-Gastaut syndromes, etc.). Complex partial seizures, right hemispheric localization of the epileptogenic focus reduce the maintenance (sustainability) of attention, and the phenomenon of the EEG pattern of continued peak-wave activity during the slow-wave sleep phase affects the selectivity and distribution of attention [1, 3].

Progressive neuronal ischemia is one of the prerequisites for epileptogenesis, as a consequence of chronic vascular insufficiency. Changes in cerebral perfusion may serve as a functional substrate for impaired cognitive/psychophysiological functions [1, 12].

Most antiepileptic drugs can cause psychotropic effects (anxiety and mood disorders that indirectly impair cognitive function) [16]. The negative effects of these drugs are decreased attention, deterioration of memory and speed of mental processes, etc. TA Ketter et al. (1999) hypothesized different profiles of antiepileptic and psychotropic effects (sedative, stimulant or mixed) of drugs used in the treatment of epilepsy [17].

Read the continuation of the article in the next issue.

Literature

- Epilepsy in neuropediatrics (collective monograph) / Ed. Studenikina V.M.M.: Dynasty. 2011, 440 p.

- Epileptic syndromes in infancy, childhood and adolescence (Roger J., Bureau M., Dravet Ch., Genton P. et al., eds.). 4 th ed. (with video). Montrouge (France). John Libbey Eurotext. 2005. 604 p.

- Encyclopedia of basic epilepsy research / Three-volume set (Schwartzkroin P., ed.). vol. 1–3. Philadelphia. Elsevier/Academic Press. 2009. 2496 p.

- Chapman K., Rho JM Pediatric epilepsy case studies. From infancy and childhood through infancy. CRC Press/Taylor&Francis Group. Boca Raton–London. 2009. 294 p.

- Berger H. An unusual manifestation of epilepsy: fever // Postgrad. Med. 1966. Vol. 40. P. 479–481.

- Lin KL, Wang HS Reverse Shapiro's syndrome: an unusual cause of fever of unknown origin // Brain Dev. 2005. Vol. 27. P. 455–457.

- Dundar NO, Boz A., Duman O., Aydin F. et al. Spontaneous periodic hypothermia and hyperhidrosis // Pediatr. Neurol. 2008. Vol. 39. P. 438–440.

- Kovalev V.V. Epilepsy. Chapter XIX. In the book: Childhood Psychiatry: A Guide for Doctors. 2nd edition, revised. and additional M.: Medicine. 1995. pp. 482–520.

- Dunn DW Neuropsychiatric aspects of epilepsy in children // Epilepsy Behav. 2003. Vol. 4. P. 98–100.

- Austin JK, Dunn DW Progressive behavioral changes in children with epilepsy // Prog. Brain Res. 2002. Vol. 135. P. 419–427.

- Boldarev A.I. Mental characteristics of patients with epilepsy. M.: Medicine. 2000. 384 p.

- Balkanskaya S.V. Cognitive aspects of epilepsy in childhood. In the book: Problems of child neurology / Ed. G. Ya. Khulupa, G. G. Shanko. Minsk: Harvest. 2006. pp. 62–70.

- Deonna T., Roulet-Perez E. Cognitive and behavioral disorders of epileptic origin in children. London. Mac Keith Press. 2005. 447 p.

- Sanchez-Carpintero R., Neville BG Attentional ability in children with epilepsy // Epilepsia. 2003. Vol. 44. S. 1340–1349.

- Tromp SC, Weber JW, Aldenkamp AP, Arends J. et al. Relative influence of epileptic seizures and of epilepsy syndrome on cognitive function // J. Child Neurol. 2003. Vol. 18. P. 407–412.

- Aldenkamp AP Effects of antiepileptic drugs on cognition // Epilepsia. 2001. Vol. 42. Suppl. 1. S. 46–49.

- Ketter TA, Post RM, Theodore WH Positive and negative psychiatric effects of antiepileptic drugs in patients with seizure disorders // Neurology. 1999. Vol. 53. P. 53–67.

V. M. Studenikin, Doctor of Medical Sciences, Professor, Academician of the Russian Academy of Economics

FSBI "NTsZD" RAMS, Moscow

Contact Information