Introduction

The onset of pregnancy in a woman with epilepsy is not only a desirable, but also a very important stage of life.

Therefore, it is necessary for a patient of fertile age to be immediately explained upon her first visit to an epileptologist that this event, like any good impromptu event, must be planned. The ability to have children with epilepsy in women is reduced on average by 2 times compared to the general population. This is due to both social and organic reasons. Antiepileptic drugs (AEDs) can disrupt the functions of the endocrine system and provoke the development of sexual disorders (hypo- or hypersexuality), obesity, hypothyroidism, polycystic ovary syndrome, delayed sexual development, menstrual dysfunction and ovulation disorders.

Pregnancy is contraindicated only in women with severe epilepsy, when taking AEDs does not help to avoid frequent generalized seizures, in addition, the woman has severe mental disorders.

Epilepsy is not a contraindication to IVF, although we should not forget that to stimulate the production of eggs, women candidates for IVF undergo massive administration of hormonal drugs. This can sometimes trigger seizures.

Somatic and neurological health of children born to mothers with epilepsy

The proportion of women suffering from epilepsy among the total number of pregnancies ranges from 0.3% to 0.5%. The problem of epilepsy and pregnancy has been repeatedly considered in the works of CL Harden (2014), AS Laganà et al. (2016), as well as MO Kinney and JJ Craig (2017) [1–3]. SF Reiter et al. (2016) note decreased “life satisfaction” among women with epilepsy both during pregnancy and after it [4].

In the study of the problem of epilepsy in pregnant women, the following main directions can be distinguished: 1) the effect of antiepileptic drugs (AEDs) on the fetus (teratogenic effect); 2) the effect of AEDs on children during breastfeeding; 3) the impact of maternal epilepsy (and AEDs?) on the cognitive functions of children.

Pregnancy outcomes in women with epilepsy

In the review works of M. Artama et al. (2017), as well as I. Borthen and NE Gilhus (2012), describe in detail the entire range of pregnancy complications in women with epilepsy [5, 6].

L. Sveberg et al. (2015) consider the problem of postpartum hemorrhage in women with epilepsy [7]. As is known, current recommendations provide for pregnant women taking enzyme-inducing AEDs to prescribe vitamin K during the last month of gestation. After examining 109 women in labor suffering from epilepsy, Norwegian researchers concluded that the risk of postpartum hemorrhage in this group of patients in terms of frequency of occurrence does not differ significantly from that in women in the control group (without epilepsy). Moreover, there were no differences between those who took and those who did not take vitamin K for prophylactic purposes [7].

A. H. Farmen et al. (2015) draw attention to the frequent phenomenon of intrauterine growth retardation (IUGR) of fetuses in women with epilepsy [8]. In particular, prospectively recorded data regarding pregnancy and pre- and perinatal factors from Oppland County (Norway) were analyzed; The final analysis included information on 166 women with epilepsy and their 287 children (the control group included 40,553 pregnancies in women without epilepsy registered in the same database). The risk of having a mass index in the zone below the 10th percentile and children belonging to the category “small for gestational age” (SGA) was significantly higher in the first group, and exposure to AEDs increased this risk (especially when women took lamotrigine); Head circumference was significantly smaller in those children whose mothers took carbamazepine [8].

T. Thomson et al. (2015) among the main (most widespread) congenital malformations registered in children whose mothers suffer from epilepsy, congenital heart defects rank first, followed by orofacial defects (cleft palate/upper lip), as well as neural tube defects and hypospadias [9]. It is assumed that the described congenital malformations are the result of exposure of the fetus to various AEDs taken by the expectant mother to control epileptic seizures.

J. Weston et al. (2016) presented a systematic review on monotherapy for epilepsy during pregnancy with an emphasis on outcomes in the form of congenital malformations in the offspring of mothers with the described pathology [10].

FJ Vajda et al. (2017) tend to link AED-induced fetal malformations with spontaneous abortions (miscarriages). Thus, according to Australian researchers, women who received AEDs and who had fetal malformations or spontaneous miscarriages in a previous pregnancy had a 2-3 times increased risk of fetal anomalies in subsequent pregnancies (compared to women who received similar therapy, but without complications in form of fetal malformation) [11]. In general, among pregnant women receiving AEDs, the likelihood of spontaneous miscarriages was higher than in previous pregnancies (without taking AEDs). It is possible that spontaneous miscarriages were associated with AED-dependent malformations that were incompatible with further fetal survival [11].

The effect of antiepileptic drugs on the fetus

Children exposed to AEDs experience problems of various kinds, but the main attention among them is usually paid to two fundamental points - congenital malformations and developmental delays. It is generally accepted that the risk of congenital anomalies (malformations) associated with AED therapy varies from 2% to 10%. Almost half a century ago, SR Meadow (1968) reported the relationship between primidone, phenytoin and phenobarbital and congenital malformations.

E. Campbell et al. (2013) demonstrated that the recurrent (repeated) risk of congenital malformations in children exposed to AEDs in utero (in the presence of a congenital malformation in a previously born child) was 16.8% (compared to 9.8% in women who had previously given birth to a child without malformations), and the relative risk was 1.73 with a 95% confidence interval from 1.01 to 2.96 [12]. The risk of having a child with malformations again reached 50% in women who had previously given birth to two children with congenital malformations. According to British researchers, there was a trend towards a higher risk of recurrent malformations in pregnant women receiving valproate (21.9%, relative risk 1.47 with 95% confidence interval 0.68–3.20) and topiramate (50%, relative risk risk 4.50 with 95% confidence interval 0.97–20.82), but not carbamazepine or lamotrigine [12].

Presenting relevant data from Boston Medical Center from 2003 to 2010, GM Deck et al. (2015) indicate that among infants exposed to AEDs in utero (if their mothers have epilepsy), the incidence of major congenital malformations (cleft lip and/or cleft palate, septal defects of the ventricles or atria, other cardiovascular anomalies systems, defects of the urogenital system) was about 4.7% [13]. Of interest is the fact that in cases where mothers took AEDs for other indications (not for the treatment of epilepsy), the incidence of large congenital malformations was even higher (5.0%). The highest level of the described malformations (10.6%) was observed in infants whose mothers received benzodiazepine monotherapy during pregnancy [13].

Recognizing the lack of precise understanding of the effects on the systems and organs of the fetal body, as potential mechanisms of the pathological effect of AEDs on fetal development, L. Etemad et al. (2012) list the following (main ones): folate-associated reactions, ischemia, reactive intermediate substances (for example, free radicals), and genetic susceptibility [14].

Regarding folate-associated reactions, according to a population-based cohort study by L. Ban et al. (2015), devoted to studying the frequency of congenital anomalies in children in the presence/absence of folic acid intake (in high doses) by their mothers while using AEDs, the following results were obtained [15]. The authors conclude that the offspring of women with epilepsy in the first trimester of pregnancy are at twice the risk of significant congenital malformations (compared to those whose mothers do not suffer from epilepsy); however, no evidence has been obtained that high-dose folic acid supplementation reduces the risk of AED-associated consequences [15].

Based on data from a population-based cohort study, J. Christensen et al. (2015) indicate that the APGAR score in children prenatally exposed to AEDs is lower than in newborns whose mothers did not take drugs of this group during pregnancy [16]. The authors reached this conclusion based on data based on an analysis of health registries in Denmark (677,021 singleton births between 1997 and 2008). The adjusted relative risk (aRR) of low APGAR score (<7 points) compared with the control group was 1.34 (95% confidence interval 0.90–2.01). When considering individual AEDs in this aspect, it turned out that the unadjusted relative risk (RR) was 1.86 for carbamazepine (95% confidence interval 1.01–3.42), 1.85 for valproate (95% confidence interval 1.04 –3.30), 2.97 for topiramate (95% confidence interval 1.26–7.01) [16].

H. Mutlu-Albayrak et al. (2016) presented a series of cases of the so-called “fetal valproate syndrome” in children of different ages [17]. At the same time, the observed patients had not only facial dysmorphism, but also other signs (anomalies in the development of the fingers of the upper extremities, deformation of the sternum, bilateral cryptorchidism, speech underdevelopment, etc.). Turkish researchers come to the conclusion that during intrauterine exposure of fetuses to valproic acid preparations, not only facial dysmorphism features can be formed, but also a number of minor skeletal anomalies, and this does not depend on the dose of valproate taken by mothers [17].

In addition to this, H. Ozkan et al. (2011) described a case of severe fetal valproate syndrome as a combination of concomitant heart disease, multicystic renal dysplasia and trigonocephaly (a variant of craniostenosis in which premature closure of the frontal suture is noted) [18].

A study by MW Green et al. (2012), was devoted to studying the risk of orofacial defects and major congenital malformations in fetuses exposed to topiramate taken by pregnant women with epilepsy [19]. The risk of the described congenital malformations when using topiramate during gestation did not exceed that for other AEDs [19]. R. Castilla-Puentes et al. (2014) revealed a predominant number of major congenital anomalies of the fetus/newborn in cases of taking topiramate for existing epilepsy (compared to taking this AED for other indications) [20].

M. Carrasco et al. (2015) first described a case of the development of gabapentin withdrawal syndrome in a newborn whose mother took this drug for a long time during pregnancy; gabapentin was previously considered absolutely safe for use during gestation [21].

The effect of AEDs on breastfeeding children

Although AEDs introduced into breast milk during breastfeeding have the potential to cause side effects and adverse events, as well as negatively impact development, most pharmacological agents are considered safe or “comparatively safe.” This circumstance is indicated by G. Veiby et al. (2016) [22]. AEDs such as barbiturates, benzodiazepines, lamotrigine and ethosuximide are considered the least safe [22].

We are talking not only about such traditional AEDs as valproic acid (valproates) and carbamazepine, but also about new AEDs - lamotrigine, topiramate, gabapentin, levetiracetam, etc.

At one time, B. Frey et al. (2002) described a case of transient cholestatic hepatitis in a newborn/infant, caused by the ingestion of carbamazepine through breast milk, which the patient’s mother took as an antiepileptic treatment [23].

E. Nordmo et al. (2009) presented a clinical situation with the development of severe apnea in an infant when lamotrigine was introduced into breast milk [24].

T. Westergren et al. (2014) observed a 2-month-old infant breastfed by a mother with epilepsy who developed topiramate-induced diarrhea [25].

R. Davanzo et al. (2013) emphasize that during breastfeeding, ethosuximide, zonisamide, as well as repeated prescriptions of clonazepam and diazepam to nursing mothers are absolutely contraindicated [26].

Lamotrigine is considered a safe AED when used by pregnant and lactating women [27]. However, among the adverse effects of lamotrigine on breastfed infants, H. Dalili et al. (2015) list thrombocytosis and severe apnea [27]. In this regard, the authors emphasize the need to monitor lamotrigine blood concentrations in infants breastfed by mothers receiving this AED [27].

The impact of maternal epilepsy on children's cognitive functions

The deficits in cognitive functions characteristic of children exposed to AEDs in the fetal period of development are reported in numerous publications by RL Bromley et al. (2010), D. McCorry and R. Bromley (2015), S. Kasradze et al. (2017), RL Bromley and GA Baker (2017) and other researchers [28–31].

In particular, N. Gopinath et al. (2015) directly indicate that children of mothers suffering from epilepsy are characterized not only by reduced intelligence, but also by attention and memory impairments [32].

M. Videman et al. (2016) in their works demonstrate the influence of prenatal AED action on brain activity in the newborn period (with assessment of neurological status according to the Hammersmith Neonatal Neurological Examination, as well as an EEG study to assess early cortical activity), and then describe the relative preservation of attention to faces in 7 months of age in children whose mothers took drugs of the specified pharmacological group during pregnancy [33, 34]. However, Finnish authors emphasize that gestational use of carbamazepine, oxcarbazepine, and valproic acid (but not lamotrigine or levetiracetam) was associated with impaired verbal development at the age of 7 months [34].

In turn, in the works of S. Hunt et al. (2006) and DW Loring (2014) showed that levetiracetam is safe for the fetus when used as monotherapy [35, 36]. R. Shallcross et al. (2014) showed that the speech, motor and cognitive development of children exposed in utero to levetiracetam taken by their mothers did not suffer [37].

The evolution of ideas about the effect of epilepsy and AEDs on the fetus and child can be traced through publications in recent years, among which the works of AC Tricco et al deserve special attention. (2014), E. E. Gerard and K. J. Meador (2015), Q. Nie et al. (2016), S. V. Thomas et al. (2017) [38–41].

The creation of pregnancy registries seems to be the most important point in the study of the potentially teratogenic and other effects of AEDs on the nervous system, as well as other organs and systems of the offspring of mothers with epilepsy.

Literature

- Harden CL Pregnancy and epilepsy // Continuum (Minneap. Minn). 2014; 20(1 Neurology of Pregnancy): 60–79.

- Laganà AS, Triolo O., D'Amico V., Cartella SM et al. Management of women with epilepsy: from preconception to post-partum // Arch. Gynecol. Obstet. 2016; 293(3):493–503.

- Kinney MO, Craig JJ Pregnancy and epilepsy; meeting the challenges over the last 25 years: The rise of the pregnancy registries // Seizure. 2017; 44: 162–168.

- Reiter SF, Bjørk MH, Daltveit AK, Veiby G. et al. Life satisfaction in women with epilepsy during and after pregnancy // Epilepsy Behav. 2016; 62:251–257.

- Artama M., Ahola J., Raitanen J., Uotila J. et al. Women treated for epilepsy during pregnancy: outcomes from a national population-based cohort study // Acta Obstet. Gynecol. Scand. 2017; Feb 7. DOI: 10.1111/aogs.13109. .

- Borthen I., Gilhus NE Pregnancy complications in patients with epilepsy // Curr. Opin. Obstet. Gynecol. 2012; 24 (2): 78–83.

- Sveberg L., Vik K., Henriksen T., Taubøll E. Women with epilepsy and post partum bleeding: Is there a role for vitamin K supplementation? //Seizure. 2015; 28:85–87.

- Farmen AH, Grundt J, Tomson T, Nakken KO et al. Intrauterine growth retardation in fetuses of women with epilepsy // Seizure. 2015; 28: 76–80.

- Tomson T., Xue H., Battino D. Major congenital malformations in children of women with epilepsy // Seizure. 2015; 28:46–50.

- Weston J., Bromley R., Jackson CF, Adab N. et al. Monotherapy treatment of epilepsy in pregnancy: congenital malformation outcomes in the child // Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2016; 11: CD010224.

- Vajda FJ, O'Brien TJ, Graham JE, Hitchcock AA et al. Antiepileptic drugs, fetal malformations and spontaneous abortions // Acta Neurol. Scand. 2017; 135(3):360–365.

- Campbell E., Devenney E., Morrow J., Russell A. et al. Recurrence risk of congenital malformations in infants exposed to antiepileptic drugs in utero // Epilepsia. 2013; 54 (1): 165–171.

- Deck GM, Nadkarni N., Montouris GD, Lovett A. Congenital malformations in infants exposed to antiepileptic medications in utero at Boston Medical Center from 2003 to 2010 // Epilepsy Behav. 2015; 51: 166–169.

- Etemad L., Moshiri M., Moallem SA Epilepsy drugs and effects on fetal development: Potential mechanisms // J. Res. Med. Sci. 2012; 17(9):876–881.

- Ban L., Fleming KM, Doyle P., Smeeth L. et al. Congenital anomalies in children of mothers taking antiepileptic drugs with and without periconceptional high dose folic acid use: A population-based cohort study // PLoS One. 2015; 10 (7): e0131130.

- Christensen J, Pedersen HS, Kjaersgaard MI, Parner ET et al. Apgar-score in children prenatally exposed to antiepileptic drugs: a population-based cohort study // BMJ Open. 2015; 5(9):e007425.

- Mutlu-Albayrak H., Bulut C., Caksen H. Fetal valproate syndrome // Pediatr. Neonatol. 2016; Jun 17. pii: S1875–9572 (16)30072–9. DOI: 10.1016/j.pedneo.2016.01.009. .

- Ozkan H., Cetinkaya M., Köksal N., Yapici S. Severe fetal valproate syndrome: combination of complex cardiac defect, multicystic dysplastic kidney, and trigonocephaly // J. Matern. Fetal Neonatal Med. 2011; 24(3):521–524.

- Green MW, Seeger JD, Peterson C., Bhattacharyya A. Utilization of topiramate during pregnancy and risk of birth defects // Headache. 2012; 52(7):1070–1084.

- Castilla-Puentes R., Ford L., Manera L., Kwarta RF Jr. et al. Topiramate monotherapy use in women with and without epilepsy: pregnancy and neonatal outcomes // Epilepsy Res. 2014; 108(4):717–724.

- Carrasco M., Rao SC, Bearer CF, Sundararajan S. Neonatal gabapentin withdrawal syndrome // Pediatr. Neurol. 2015; 53(5):445–447.

- Veiby G., Bjørk M., Engelsen BA, Gilhus NE Epilepsy and recommendations for breastfeeding // Seizure. 2015; 28:57–65.

- Frey B., Braegger CP, Ghelfi D. Neonatal cholestatic hepatitis from carbamazepine exposure during pregnancy and breastfeeding // Ann. Pharmacother. 2002; 36(4):644–647.

- Nordmo E., Aronsen L., Wasland K., Småbrekke L. et al. Severe apnea in an infant exposed to lamotrigine in breast milk // Ann. Pharmacother. 2009; 43(11): 1893–1897.

- Westergren T., Hjelmeland K., Kristoffersen B., Johannessen SI et al. Probable topiramate-induced diarrhea in a 2-month-old breast-fed child — A case report // Epilepsy Behav. Case Rep. 2014; 2:22–23.

- Davanzo R., Dal Bo S., Bua J., Copertino M. et al. Antiepileptic drugs and breastfeeding // Ital. J. Pediatr. 2013; 39:50.

- Dalili H., Nayeri F., Shariat M., Asgarzadeh L. Lamotrigine effects on breastfed infants // Acta Med. Iran. 2015; 53 (7): 393–394.

- Bromley R.L., Mawer G., Love J., Kelly J. et al. Early cognitive development in children born to women with epilepsy: a prospective report // Epilepsia. 2010; 51(10):2058–2065.

- McCorry D., Bromley R. Does in utero exposure to antiepileptic drugs lead to failure to reach full cognitive potential? //Seizure. 2015; 28:51–56.

- Kasradze S., Gogatishvili N., Lomidze G., Ediberidze T. et al. Cognitive functions in children exposed to antiepileptic drugs in utero - Study in Georgia // Epilepsy Behav. 2017; 66: 105–112.

- Bromley RL, Baker GA Fetal antiepileptic drug exposure and cognitive outcomes // Seizure. 2017; 44:225–231.

- Gopinath N, Muneer AK, Unnikrishnan S, Varma RP et al. Children (10–12 years age) of women with epilepsy have lower intelligence, attention and memory: Observations from a prospective cohort case control study // Epilepsy Res. 2015; 117:58–62.

- Videman M., Tokariev A., Stjerna S., Roivainen R. et al. Effects of prenatal antiepileptic drug exposure on newborn brain activity // Epilepsia. 2016; 57(2):252–262.

- Videman M., Stjerna S., Roivainen R., Nybo T. et al. Evidence for spared attention to faces in 7-month-old infants after prenatal exposure to antiepileptic drugs // Epilepsy Behav. 2016; 64 (Pt A): 62–68.

- Hunt S., Craig J., Russell A., Guthrie E. et al. Levetiracetam in pregnancy: preliminary experience from the UK Epilepsy and Pregnancy Register // Neurology. 2006; 67(10): 1876–1879.

- Loring DW First-degree relative risk: in utero levetiracetam and valproate exposure // Epilepsy Curr. 2014; 14 (4): 186–188.

- Shallcross R, Bromley RL, Cheyne CP, García-Fiñana M et al. In utero exposure to levetiracetam vs valproate: development and language at 3 years of age // Neurology. 2014; 82(3):213–221.

- Tricco AC, Cogo E., Angeliki VA, Soobiah C. et al. Comparative safety of anti-epileptic drugs among infants and children exposed in utero or during breastfeeding: protocol for a systematic review and network meta-analysis // Syst. Rev. 2014; 3:68.

- Gerard EE, Meador KJ An update on maternal use of antiepileptic medications in pregnancy and neurodevelopmental outcomes // J. Pediatr. Genet. 2015; 4(2):94–110.

- Nie Q., Su B., Wei J. Neurological teratogenic effects of antiepileptic drugs during pregnancy // Exp. Ther. Med. 2016; 12(4):2400–2404.

- Thomas SV, Jose M., Divakaran S., Sankara Sarma P. Malformation risk of antiepileptic drug exposure during pregnancy in women with epilepsy: Results from a pregnancy registry in South India // Epilepsia. 2017; 58(2):274–281.

V. M. Studenikin*, 1, Doctor of Medical Sciences, Professor, Academician of the Russian Academy of Economics S. Sh. Tursunkhuzhaeva**, Candidate of Medical Sciences

* FGAU NNPCZD of the Ministry of Health of Russia, Moscow ** City Children's Clinical Hospital No. 5, Tashkent

1 Contact information

Preconception preparation for women with epilepsy

Pregravid (from Latin gravida

- pregnant) preparation - a set of preventive, diagnostic and therapeutic measures, the result of which is the readiness of future parents to fully conceive, bear and give birth to a healthy child. Planning a pregnancy is not just about taking vitamins, quitting drinking and smoking 1-2 months in advance. before conception. Preconception preparation begins 6–10 months in advance. before the desired pregnancy and includes a specific list of procedures.

Pregravid preparation takes place in several stages:

Medical examination of spouses.

Preparing a couple for conception, a woman for bearing a child.

Determining favorable days for conception.

The number and scope of studies before a planned pregnancy are determined for each patient individually by a therapist, gynecologist, or geneticist. From the point of view of an epileptologist, it is necessary to determine the concentrations of AEDs in the blood plasma; perform a general blood test to determine platelet levels; biochemical blood test to determine the level of ALT, AST, bilirubin, alkaline phosphatase; take an electroencephalogram (EEG) or conduct video-EEG monitoring. In some cases, when planning pregnancy, it is advisable to conduct an ultrasound examination of the uterus and its appendages, as well as a number of hormonal studies that reflect the function of the woman’s reproductive system. To select the dose of AED, regular testing of the concentration of the drug in the blood is indicated, and to maintain a constant concentration, it is advisable to use dosage forms with a slow release (durant forms).

An indication for an unscheduled determination of the concentration of AEDs in the blood before pregnancy is an increase in frequency/severity of attacks or the appearance of symptoms of intoxication.

During the preconception period, it is recommended to consult a geneticist to determine the risk of epilepsy in the unborn child. Epilepsy is not a hereditary disease, but in some cases it can be inherited. The risk of transmitting epilepsy to a child from mother with genetic epilepsies is on average 10%, with unknown etiology and structural epilepsy - 3%. The risk of paternal transmission of epilepsy is on average 2.5%. If both parents suffer from epilepsy, the risk of a child inheriting epilepsy increases to 10–12%. If a woman suffers from structural or unknown etiology epilepsy, the risk for the unborn child increases threefold compared to the general population, but in the case of genetic generalized or focal epilepsy - 10 times.

You need to undergo genetic testing if:

both partners in a couple have epilepsy;

the couple already has a child with epilepsy;

in the family, one or both parents had cases of epilepsy, developmental defects (congenital cleft palate or cleft lip, finger deformities, etc.) and hereditary diseases;

the patient had 2 or more spontaneous miscarriages, cases of fetal or newborn death.

The main goal of the doctor is to achieve complete control of the attacks before the desired pregnancy occurs. An important indicator is the duration of the absence of attacks in the patient before pregnancy: if for 9 months. If there are no seizures, then there is a very high probability that there will be no seizures during pregnancy. However, it is difficult to predict the course of each specific pregnancy.

It is not advisable to stop taking AEDs during the period of conception. A woman should be warned that the risk of developing congenital anomalies of the fetus while taking AEDs increases threefold, but that refusal to take the drug is fraught with even more serious consequences - injury or death of the fetus in the event of an epileptic seizure. It is necessary to explain to the patient that sudden cessation of taking AEDs sharply increases the risk of attacks, can lead to failure of remission, and increase the frequency of existing attacks.

The administration of folic acid is indicated to prevent pathological effects on the fetus and reduce the risk of miscarriage (spontaneous miscarriages). Folic acid supplements must be prescribed before the patient becomes pregnant, since for most women pregnancy itself is a surprise. It is recommended to start taking folic acid supplements 3 months in advance. before the expected pregnancy at a dosage of 3–5 mg/day and continue taking until 14 weeks. pregnancy. In addition to folic acid, the use of complex vitamin preparations recommended for pregnant women is also indicated. Anemia treatment is carried out before pregnancy with the use of drugs containing iron and folic acid.

Since sodium valproate is more likely than carbamazepine to have a teratogenic effect, and the combination of valproate and lamotrigine is especially dangerous, carbamazepine is the drug of choice, but only if there are no contraindications to its use (most forms of genetic generalized epilepsy, secondary bilateral synchronization on the EEG in patients with focal epilepsy). Information about the effect of “new” AEDs on the intrauterine development of the fetus is still insufficient, therefore, unless there is an urgent need, it is better to refrain from introducing them into therapy during the period of preparation for pregnancy.

The doctor is at a great disadvantage. By allowing a woman to become pregnant and give birth to a child, he takes on additional responsibility and new risks. If teratogenic consequences occur, the patient and her relatives will attribute this to the AEDs prescribed by the doctor; in case of exacerbation of the disease, the cause of suffering will be considered to be incorrectly selected therapy, and not the long-awaited pregnancy. In addition, the question of having a child in patients with epilepsy, for various reasons, does not arise at a very young age.

Features of management of pregnant women with epilepsy

At this period of life, the leading doctor is an obstetrician-gynecologist, with whom the patient should be regularly monitored. Until the 28th week. examinations are carried out once a month, from the 28th to the 36th week - once every 2 weeks, and after the 36th week. - every week. Throughout pregnancy, a woman should be observed by an epileptologist: with complete control of seizures - once every 2 months, with repeated partial seizures - once a month. The patient should be warned about the need to consult a doctor if attacks become more frequent. If there is any concomitant pathology: diabetes mellitus, anemia, arterial hypertension, kidney disease, etc., supervision of related specialists is required. Most gynecologists, neonatologists and pediatricians are very afraid of the negative effects of AEDs on the body of the mother and fetus, while at the same time they do not attach such importance to the drugs they prescribe. However, the prescription of AEDs is the competence of an epileptologist; changing the treatment regimen is possible only in agreement with him. If other specialists make adjustments to therapy or insist on discontinuing AEDs, then you need to inform your epileptologist about this.

Currently, there is no reliable data on the increased incidence of pregnancy complications (preeclampsia, arterial hypertension, spontaneous abortions, changes in the frequency of seizures, status epilepticus) in women with epilepsy taking AEDs compared to the general population.

During pregnancy, the minimum effective doses of AEDs should be used, preferably in monotherapy [1]. Taking one drug reduces the risk of possible fetal development defects. The dose of AEDs should be as low as possible, but one that does not cause generalized seizures. Changing the drug to an analogue may lead to an increase in attacks. It is recommended to continue taking the same drug from the same manufacturer.

An important safety factor is the use of drugs with controlled release of the active substance, which can be used 2 times a day. This eliminates concentration peaks that have a particularly adverse effect on the fetus.

Nausea and vomiting due to toxicosis can significantly complicate the use of AEDs. To avoid a decrease in the concentration of drugs in the blood, you can use intravenous or rectal forms. With frequent vomiting (up to 20 or more times a day), hospitalization is indicated.

Unfortunately, none of the “first aid drugs for seizures” are registered in Russia. The only available way to prevent an attack in Russian conditions is the use of diazepam tablets under the tongue when an attack is anticipated. Taking additional doses of AEDs, as a rule, does not make sense, since their absorption period is quite long.

Pregnant women are contraindicated in taking psychotropic drugs and strong sleeping pills. Sleep disorders should be treated with non-drug methods: herbal medicine (decoction of calamus, fireweed, oregano, chamomile, mint, linden, peony, etc.); psychotherapy (listening to quiet relaxing music before bed); aromatherapy; compliance with sleep hygiene, as well as work and rest regimes.

Fluoroquinolones are contraindicated in epilepsy. The use of some other groups of antibiotics and antimicrobials: macrolides, high doses of penicillins should also be avoided if possible. However, if inflammation is present, the benefit of antibiotic therapy may outweigh the risk.

Pregnant women with epilepsy are contraindicated for physiotherapy in the head and neck area.

Valproate intake is associated with weight gain. However, weight gain also occurs during pregnancy. In most cases it is impossible to say unequivocally what explains weight gain - taking valproate or an abnormal course of pregnancy. To correct body weight, observation by a gynecologist-endocrinologist and diet are indicated. Replacing valproate with another AED during pregnancy is not justified; it can lead to the occurrence/increase of attacks and is only permissible if absolutely necessary.

In 15–20% of women, the number of attacks may increase, more often in the first or third trimester of pregnancy. Increased seizure frequency cannot be predicted based on seizure type, duration of epilepsy, or increased frequency of seizures during a previous pregnancy. Even the presence of hormonal-dependent epilepsy is not a prognostic factor for increased frequency of epileptic seizures during pregnancy. The resumption of attacks may be due to the pharmacokinetics of AEDs during pregnancy.

The most common triggers for seizures during pregnancy are emotional stress and sleep deprivation. An increase in body temperature can provoke attacks and accelerate the elimination of AEDs. Hypoglycemia (low blood glucose levels) and alcohol consumption can also lead to the occurrence/increasing frequency of attacks. Seizures may become more frequent after a traumatic brain injury. Therefore, you need to lead a correct lifestyle, carefully monitor your health, and observe a work and rest schedule. However, quite often attacks occur completely unpredictably, and a “healthy lifestyle” does not prevent them. Therefore, it is necessary to take a sufficient dose of AEDs, and not just eliminate provoking factors.

Severe and moderate forms of ARVI or influenza aggravate the course of epilepsy and can provoke the appearance/increase in seizures. Despite this, specific prophylaxis (vaccination) is not recommended, because, firstly, the effect of a number of vaccines on the fetus has not been adequately studied, which means they are potentially dangerous for the fetus, and secondly, an adverse reaction to their introduction is an increase in temperature. To prevent influenza in pregnant women, natural immunomodulators (“folk remedies”) are used, as well as hygiene measures (avoid crowded places, wash your hands and face, wash your nose and eyes after returning from the street).

Generalized seizures are considered the most dangerous for both mother and child. During their development, many factors have a negative impact on the body of the mother and child. Focal seizures can generally be considered to have no impact, but it is important to remember that they can take a generalized form.

The study of the concentration of AEDs in the blood during pregnancy should be carried out repeatedly, at least once every 2 months, and in the case of recurring attacks - monthly. This must be done not only because during pregnancy the metabolism of AEDs or drug concentrations may change due to weight gain, but also to monitor compliance.

Plasma concentrations of lamotrigine may decrease significantly during pregnancy. Also, at the end of the first trimester, due to increased clearance, it may be necessary to increase the daily dosage of levetiracetam.

To assess the full functioning of the placenta and early diagnosis of fetoplacental insufficiency, it is advisable to study the hormones of the fetoplacental complex (placental lactogen, progesterone, estriol, cortisol) monthly from the end of the first trimester of pregnancy.

Particular attention is paid to the study of alpha-fetoprotein. At the end of the last century, it was found that in cases of neural tube defects in the fetus (anencephaly and spina bifida), the content of alpha-fetoprotein, a protein synthesized in the fetal liver, increases in the mother’s blood serum. With neural tube defects, alpha-fetoprotein penetrates through the capillary wall in the area of the defect into the amniotic fluid, and from there into the mother's bloodstream. With the introduction into clinical practice of a method for determining the level of alpha-fetoprotein in maternal blood serum, it was possible to increase the accuracy of diagnosing neural tube defects of the fetus. Thus, using this method, up to 97–98% of cases of anencephaly are detected. Determination of serum alpha-fetoprotein levels is also used to diagnose multiple pregnancies, anterior abdominal wall defects and other fetal malformations. It has been established that with Down syndrome in the fetus, the content of alpha-fetoprotein in the mother's blood serum decreases. Determination of alpha-fetoprotein levels is carried out at 15–20 weeks. pregnancy, the most informative study is at 16–18 weeks; it is repeated if changes are detected during ultrasound.

Fetal ultrasound is performed at 19–21 weeks. pregnancy to exclude developmental anomalies. A high level of alpha fetoprotein in the maternal serum is an absolute indication for fetal ultrasound.

An important diagnostic method is cardiotocography. This method allows you to obtain more objective information about the state of the fetal cardiovascular system compared to auscultation of heartbeats. Cardiotocography evaluates the fetal heart rate, its variability, the presence of accelerations (increased heart rate by 15–25 beats per minute during fetal movements) and decelerations (decrease in heart rate by no more than 30 seconds during contractions). The normal state of the fetus corresponds to a heart rate of 120–160 per minute, good heart rate variability (mainly due to accelerations) and the absence of high-amplitude decelerations. The value of this research method lies in the simultaneous determination of fetal heartbeats and uterine motility. The method allows you to diagnose intrauterine fetal hypoxia due to fetoplacental insufficiency.

The patient should warn the obstetrician that a number of medications are contraindicated for her: nootropics, analeptics, psychotropic drugs (with the exception of fractional administration of small doses of benzodiazepines in order to potentiate pain relief during childbirth).

Due to the potential for vitamin K deficiency when taking enzyme-inducing AEDs (carbamazepine) in the last weeks of pregnancy, it is advisable to prescribe vitamin K to a woman using these AEDs at a dose of 10–15 mg/day.

Pregnancy and epilepsy: seizures and how to minimize them

Joan Rogin, Director, Center for Paroxysmal Disorders, Neuroscience Clinic, Minneapolis, Minnesota, USA.

Epilepsy is one of the most common neurological diseases of women during the reproductive period. There are 1.1 million women of childbearing age in the United States with epilepsy. With a birth rate of 3-5 per 1000 births, about 24,000 children are born to mothers with epilepsy every year. Women with epilepsy may experience certain specific complaints during pregnancy, but despite this, the vast majority of these women give birth to normal children, and pregnancy has almost no effect on the course of epilepsy.

The formation of a unified strategy to minimize the risk of complications during pregnancy in women with epilepsy helps to improve the prognosis for mother and child.

Frequency of attacks during pregnancy.

Fortunately, for most women, the frequency of attacks decreases or remains the same during pregnancy. However, 15% to 30% of women may experience an increase in the number of seizures, most often in the first or third trimester of pregnancy. An increase in seizure frequency cannot be predicted based on the type of seizures a woman has, the duration of her epilepsy, or even the presence of increased seizure frequency in a previous pregnancy. Even the presence of catamenial epilepsy, i.e. epilepsy, in which the occurrence of seizures is closely related to certain phases of the menstrual cycle, is not a prognostic factor for the increase in epileptic seizures during pregnancy. Possible triggers for this increase include hormonal changes, disturbances in water-salt metabolism, stress, and a decrease in the level of antiepileptic drugs in the blood. Inadequate sleep and non-compliance with prescribed medications are obviously the most important factors that women with epilepsy can control themselves, as well as regular visits to a neurologist-epileptologist throughout pregnancy.

Risk due to the development of seizures and taking antiepileptic drugs.

Both seizures that occur during pregnancy and the use of antiepileptic drugs are associated with a certain risk. The risk of developing an attack is directly related to the type of attack. Focal seizures may not be as dangerous, but they can become generalized, and generalized tonic-clonic seizures carry a high risk for both mother and child. These risks include injuries from falls or burns, increased risk of preterm birth, miscarriage, and suppressed fetal heart rate. Seizure control is necessary because, according to epileptologists, the risk of developing seizures exceeds the risk of taking antiepileptic drugs, the use of which can be minimized by using specific approaches.

The risk of a child developing various complications when using antiepileptic drugs during pregnancy includes the formation of congenital malformations or developmental defects. In the general population, the appearance of congenital malformations is observed in 2-3% of cases. However, they cannot always be predicted or prevented. In women with epilepsy, the risk of having a child with a birth defect doubles to 4-6%, but overall remains low. There is an increased risk when using polytherapy, i.e. using more than one type of drug and at a high dose of medication. The role of the genetic factor is also clearly visible here. The presence of congenital malformations in a previous pregnancy or family history increases the risk of their development in the current pregnancy. In this case, genetic counseling is necessary. The most common malformations include defects of the facial skull such as cleft lip and cleft palate, which in most cases are treated surgically. Heart defects and defects of the genitourinary system may also occur.

Information on the safety of new antiepileptic drugs in pregnancy is very limited. Somewhat more data is available on classical antiepileptic drugs. According to existing recommendations, the most effective drug with minimal side effects should be used.

While most of our antiepileptic drugs can and are used safely, some have specific increased risks. Valproate, used in the first 28 days of pregnancy, causes the development of neural tube defects in 1-2% of cases. In the general population, this risk is reduced by folate supplementation during neural tube closure in the early first trimester. Although it may not be as protective in women with epilepsy, folate should be taken daily before they become pregnant, as most women do not know they are pregnant until the time the neural tube closes (24-28 days). after conception). A daily multivitamin containing 0.4 mg folate, as well as an additional 1 to 4 mg folate supplement, is recommended for all women of childbearing age. Selenium and zinc found in multivitamins with minerals will also provide some benefits. Vitamin K1 should be taken in the last month of pregnancy to prevent rare hemorrhages in newborns.

Strategies to minimize risk.

It is most important that women receive accurate information before and during pregnancy. The lowest possible dose of an antiepileptic drug that will not cause seizures is recommended.

Taking a single drug, monotherapy, will reduce the risk of birth defects, reduce drug interactions, reduce side effects, and improve doctor-patient communication (compliance).

Monitoring drug levels in the blood is very important. Antiepileptic drug levels should be monitored throughout pregnancy and after pregnancy. Levels of all antiepileptic drugs decrease during pregnancy, some more than others. The dose may need to be adjusted again. Since levels rise after childbirth, drug monitoring in the post partum period is also needed to reduce side effects. An obstetrician-gynecologist should monitor the child while determining maternal serum alpha-fetoprotein and conducting a high-resolution or level 2 ultrasound examination. Epilepsy itself is not an indication for cesarean section and most women give birth naturally.

Although antiepileptic drugs pass into breast milk, breastfeeding is encouraged. In most cases, breastfeeding is safe because the baby has been exposed to antiepileptic drugs during pregnancy and the absolute amount of the drug in milk is small. Strategies such as taking antiepileptic drugs immediately after feeding are designed to minimize the amount of drug during feeding. Breastfeeding is usually safe and recommended due to its high value for the baby.

It is recommended to plan pregnancy with a doctor, regular consultations and drug monitoring of antiepileptic drugs during pregnancy. It is very important to adhere to medications, as well as adequate sleep and rest. It is necessary to pay attention to proper nutrition with control of weight gain and taking vitamins with additional folates before, during and after pregnancy. Keeping all these factors in mind, most women with epilepsy will give birth to a normal, healthy baby.

Translation from English: neurologist, Ph.D.

honey. Sci. E. P. Tverskaya Pregnant women with epilepsy are advised by:

- Doctor of Medical Sciences, Professor V. A. Karlov

— Doctor of Medical Sciences, Professor I. A. Zhidkova

Features of the labor period in women with epilepsy

Women with epilepsy have a higher risk of bleeding, weak labor and preeclampsia (the risk of the latter is 2 times higher than in the population), placental abruption, premature birth; obstetrics are 2 times more likely to be carried out by vacuum extraction of the fetus or cesarean section. To reduce the risk of complications, it is necessary to establish complete control over attacks.

The likelihood of an epileptic seizure during labor and within 24 hours after birth is higher than the likelihood of an epileptic seizure during other periods of pregnancy. First of all, this is due to skipping an AED dose.

Epilepsy is not a contraindication for natural delivery, and drug management of labor and pain management do not differ from generally accepted standards. In most cases, long-term epidural analgesia can be used.

Indications for cesarean section are increased frequency of epileptic seizures, convulsive seizures more often than once a week. in the last trimester of pregnancy, serial or status epilepsy in the prenatal period, fetal hypoxia, weakness of labor, convulsive attack during childbirth.

Management of the postpartum period in women with epilepsy

The patient should be warned about the need to carefully follow the AED regimen during this period, since there is a risk of decompensation of epilepsy in the postpartum period due to physical overexertion, stress, increased drug load, and increased estrogen activity.

Also, after delivery, symptoms of an AED overdose may appear due to a decrease in the mother’s body weight, blood loss during childbirth, and metabolic changes. If symptoms of neurotoxicity appear - drowsiness, diplopia, nystagmus, ataxia, an urgent study of the concentration of AEDs in the blood is necessary. If the dosage of the drug was increased during pregnancy, it is advisable to return to the daily dose used before pregnancy. If the mother has no seizures and the child has no side effects from AEDs, changing the dose is not advisable. Another danger lies in the increased frequency of attacks due to child care and night awakenings.

Breastfeeding a newborn is quite possible, since the dose of AEDs that enter the child’s body with milk is not comparable to the amount of the drug entering the fetus’s body through the placenta. An exception should be made for phenobarbital and lamotrigine. The mechanisms for their elimination from the body of a newborn are unformed, which can lead to the accumulation of the drug [1].

AEDs acted on the fetus throughout pregnancy, and their content in breast milk was significantly lower than in the blood of a pregnant woman. In addition, you can reduce the amount of the drug in milk by taking AEDs after feeding.

The most common complication in newborns is skin manifestations in the form of allergic reactions. Cases of hemorrhagic complications (increased bleeding) have been described. The use of phenobarbital during pregnancy can lead to both sedative symptoms (drowsiness, weak sucking, muscle weakness, lethargy, lethargy) and withdrawal syndrome (motor agitation, restless sleep, frequent causeless crying), if for some reason breastfeeding milk stops.

If a newborn exhibits low activity, lethargy during feeding, gastrointestinal disorders and other symptoms suspicious of intoxication, then it is better to switch to artificial feeding.

Determining the concentration of the drug in breast milk has no practical meaning. It is much more important that the child has clinical manifestations of the effects of AEDs. The dose of the drug that reaches the baby through breast milk depends on the amount of milk sucked. In children over 6 months of age who have already been introduced to complementary foods, the dose of the drug received decreases as the child grows.

For children at high risk of seizures, an exemption from preventive vaccinations is provided. Vaccination is undesirable in the acute phase of infectious diseases accompanied by an increase in body temperature. Routine vaccination is postponed until the end of acute manifestations of the disease. It is possible to deviate from DTP vaccination or replace it with ADSM.

Women with epilepsy should breastfeed while lying on the bed or sitting on the floor, preferably in the presence of relatives. This will minimize the risk of injury to the mother and/or baby during an attack.

Epilepsy (G-40) is a chronic brain disease characterized by repeated spontaneous attacks in the form of disorders of motor, sensory, autonomic, mental or mental functions resulting from excessive neuronal discharges in the cerebral cortex [1].

Epilepsy is one of the most common diseases of the nervous system, occurring with equal frequency throughout the world, regardless of race. Worldwide, 0.5 to 1% of the population suffers from this disease, which is about 40 million people [2]. The annually registered incidence of epilepsy, excluding febrile convulsions and single paroxysms, varies from 20 to 120 new cases per year per 100,000 population, with an average of 70 cases per 100,000 population. Among the total number of patients, from 25 to 40% are women of reproductive age, while in 13% of women the manifestation of the disease occurs during pregnancy, and in 14% seizures are observed only during pregnancy [3, 4]. According to modern data, the disease can be caused by many exogenous and endogenous factors. There are idiopathic, symptomatic and cryptogenic epilepsy. However, this division of epilepsy into three forms does not mean that each case of the disease belongs to one of these groups - one can only assume the probable cause of the disease. Currently, advances in genetics have made it possible to identify many new idiopathic forms, and in connection with the development of methods of neuroradiology and brain imaging, there is a gradual reduction in cryptogenic forms of epilepsy. The concept of “chain pathogenesis of epilepsy” by G.B. remains generally accepted. Abramovich [5], according to which unfavorable heredity contributes to the fact that problems of the perinatal period acquire a pathogenic role. The main genetically determined factor in the development of epilepsy is the predisposition of neurons to excessive synchronization of rhythmic activity.

This problem has become especially relevant in the last decade due to the increase in the number of pregnancies and births among women of reproductive age. Over the past 20 years, there has been a 4-fold increase in the number of pregnancies and births in women with epilepsy, in which approximately 3–4 children out of 1000 are born to mothers taking antiepileptic therapy (AET) [1–3]. Epilepsy is a high-risk disease: maternal mortality is 10 times higher in women with epilepsy than in patients without this extragenital disease; in economically developed countries, more women die from epilepsy during pregnancy than from preeclampsia [5].

There are many risk factors (RFs) for brain damage: congenital anomalies (malformations of the cerebral cortex), intrauterine infections, chromosomal syndromes, hereditary metabolic diseases, birth injuries to the structures of the central nervous system, tumors, infections of the nervous system, traumatic brain injuries , the effects of toxic substances, cerebrovascular accidents, metabolic disorders, fevers, degenerative brain diseases and hereditary predisposition [5, 6]. It has been noted that in families in which there are relatives suffering from epilepsy, the likelihood of a child developing epilepsy is higher than in families in which the disease is absent. If the father of an unborn child suffers from epilepsy, then the probability of inheritance does not exceed the general indicators (1%) and the majority are born healthy [4].

Taking into account risk factors, preconception preparation is necessary to achieve disease compensation, preferably with monotherapy using a minimum dosage of AEDs. It is also undeniable to prescribe folic acid supplements to all women with epilepsy planning pregnancy, since all AEDs have a teratogenic effect [6, 7].

Considering the high risk of developing congenital pathology of the central nervous system in the fetus (CNS), including those associated with the teratogenic effects of AEDs, consultation with a geneticist is mandatory before 17 weeks of pregnancy. If there is a high risk of developing congenital malformation and/or chromosomal mutations, it is necessary to use invasive methods of prenatal diagnosis (chorionic villus biopsy, cordocentesis, amniocentesis with determination of the concentration of α-fetoprotein in the amniotic fluid and cytogenetic study) [6, 8, 9].

Epilepsy can be a manifestation of many hundreds of hereditary diseases (HDs) and often their leading manifestation [10, 11]. Currently, there is no classification of NP accompanied by epilepsy, so definitive diagnosis is only possible with laboratory confirmation. Existing N.B. can be divided into three groups according to the substrate of “breakage” of hereditary material: chromosomal, genetic (caused by mutation of nuclear DNA) and associated with mutation of mitochondrial DNA [10–12].

In modern epileptology, three main areas are discussed in relation to the perinatal outcome of pregnancy: the impact of epileptic seizures during pregnancy on the mother and fetus; teratogenic risk when taking AEDs and the risk of inheriting epilepsy [12].

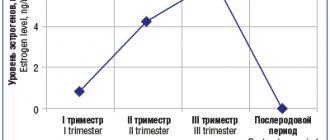

According to observational data [5, 13], in 54-80% of women the frequency of seizures during pregnancy does not change, but approximately 5-32% note an increase in seizures. This is probably due to the fact that pregnancy is a risk factor that can affect the brain due to changes in the ratio of progesterone and estrogen. Estrogens provoke epileptic seizures by changing the permeability of cell membranes to calcium and reducing the influx of chloride through γ-aminobutyric acid (GABA) receptors, while progesterone, on the contrary, reduces the excitability of cortical neurons by increasing the action of GABA [14]. Therefore, even physiological pregnancy in 20-25% of cases can lead to an increase in attacks during pregnancy, in 30-35% - to an increase in attacks in the first trimester, in 5% - both during and after pregnancy [6].

Another risk factor that influences the course of pregnancy and epilepsy is an increase in the activity of cytochrome P450, which can enhance the synthesis of procoagulants and fatty acids, leading to changes in the metabolism of drugs and a decrease in the concentration of AEDs in the blood [15]. The increase in attacks is explained by changes in a woman’s body caused by pregnancy: an increase in the volume of distribution of the drug and its higher elimination by the kidneys, altered activity of liver enzymes, and a decrease in the level of proteins in the blood plasma [16].

There are currently no recommendations for the management of pregnancy in patients with epilepsy, but the main goal is seizure control. The opinion of researchers on studying the effect of epilepsy on pregnancy is contradictory; some believe that epilepsy increases the risk of obstetric hemorrhage, fetal growth restriction and hypertensive disorders during pregnancy [5, 8, 13], according to others [1, 2, 17], indicators in pregnant women with epilepsy, they practically do not differ from those in healthy pregnant women in the development of gestosis, the threat of spontaneous abortion and premature birth. At the same time, the perinatal mortality rate exceeds the average statistical values by 1.5-2 times; the birth of children with a low Apgar score and a body weight of less than 2500 g is more often observed - in 7-10% of cases [17]. Focal epileptic seizures are considered relatively harmless. More attention needs to be paid to generalized tonic-clonic seizures (GTC), which are accompanied by severe hypoxic disorders and pose a serious danger to the health of the mother and fetus. In this case, there is a high risk of injury due to falls or burns, an increased risk of premature birth and miscarriage, and suppression of the fetal heart rate [18]. Planning, monitoring and management of pregnancy in patients with epilepsy should begin with pregravid preparation (PP) for pregnancy.

Planning pregnancy is possible with stable drug remission for more than 3 years, the presence of epilepsy with rare generalized and secondary generalized seizures - no more than one generalized tonic-clonic seizure (GTCS) per year, with rare complex focal epileptic seizures (EP) (without ambulatory automatisms and falls ) - no more than one per quarter.

When planning pregnancy, a prerequisite is the prevention of congenital birth defects and fetal abnormalities associated with the teratogenic effects of AEDs. For this purpose, the administration of folic acid before conception (2-3 months) and during the first trimester of pregnancy (up to 13 weeks) is indicated [9, 14, 19, 20], but the administration of folic acid preparations should not be uncontrolled, since high the level of folate in the blood serum (in cases of vitamin B5 overdose) is a risk factor for provocation of E.P. It must be remembered that in women suffering from epilepsy, when taking AEDs with enzyme-inducing properties (carbamazepine, barbiturates), it is possible to increase the level of liver enzymes (LDH, aspartate aminotransferase - AST, alanine aminotransferase - ALT, GGT, ALP) in the blood, so an assessment of the level is necessary these enzymes [16, 18, 21, 22].

Medical indications for termination of pregnancy are intractable epilepsy, status epilepsy and pronounced personality changes (epileptic psychoses, aggression, egocentrism, malice), which pose a threat to the life of the mother and fetus [19, 22], however, in modern obstetrics these indications are relative, since termination of pregnancy can only be carried out with the consent of the woman. In this case, the doctor must make a note in the outpatient chart about contraindications to continuing pregnancy and familiarize the patient with the possibility of complications [14, 15, 18].

When pregnancy occurs, careful monitoring of the pregnant woman is necessary. In the compensated course of the disease with remission of epileptic seizures, the regularity of visiting a neurologist-epileptologist is once every 2 months, with a consultation with a neurologist within 33-35 weeks to resolve the issue of delivery [20, 21, 23]. Pregnant women visit an obstetrician-gynecologist at a scheduled time in accordance with accepted standards [24].

Diagnosis of epilepsy in pregnant women does not cause difficulties and does not differ from that in patients outside pregnancy; it includes collecting an anamnesis from the patient and/or from people who observed seizures [25, 26].

Differential diagnosis of epilepsy must be carried out with hypoxic-ischemic conditions, encephalitis, drug withdrawal syndrome, metabolic encephalopathy, structural brain damage, mental illness, toxic effects of drugs, hysterical (conversion) attacks, syncope, eclampsia [22, 23, 27] .

It is important for an obstetrician-gynecologist to be able to distinguish EP from seizures during eclampsia. EP is preceded by an aura, after which a short-term unconsciousness is observed, there are no changes in urine analysis, prolonged constriction of the pupils is noted, involuntary urination is possible, tendon reflexes are decreased [3, 4, 28], and with eclampsia, tendon reflexes are increased, small fibrillary muscle twitches are observed face with further spread to the upper extremities (with epilepsy they do not occur), tonic contractions of all skeletal muscles, loss of consciousness, apnea, cyanosis, tongue bite, duration of convulsions up to 30 s, clonic convulsions spread to the lower extremities, followed by a deep breath, restoration of breathing , consciousness and complete amnesia [22—24, 29].

Particular attention should be paid to laboratory tests - biochemical blood test: determination of total protein, protein fractions, potassium, sodium, bilirubin, ALT, AST, amylase, creatinine, urea, calcium, magnesium. Taking into account the negative impact of AEDs on folate metabolism, it is recommended to determine the level of folic acid, homocysteine, cyanocobalamin in the blood serum 3 months before the planned pregnancy and in the first trimester of pregnancy [30-32]. A new method is the study of pharmacogenetic markers of sensitivity to AEDs, valproic acid - determination of polymorphism of the genes of liver cytochrome P450 isoenzymes CYP2C9*2, CYP2C9*3, CYP2A6, CYP2B6, CYP1A1, CYP2D6, CYP2E1 (1), CYP2E1 (2), to carbamazepine - determination polymorphism of cytochrome genes CYP3A4, CYP3A5, transporter gene MDR1 (C3435T); to lamotrigine - polymorphism of the glutathione-S-transferase gene (mGSTM1 and tGSTT1), glutathione-S-transferase gene n (1) and n (2), sodium channel gene ( SCN1VS5N

) and the uridine phosphate glucuronosyltransferase gene (UGT1A4) [31–34]. According to the order of the Ministry of Health of the Russian Federation No. 572n dated November 1, 2012 “On approval of the procedure for providing medical care in the field of obstetrics and gynecology (except for the use of assisted reproductive technologies),” enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) and ultrasound examination ( Ultrasound) to detect a neural tube defect, and at 18-21 weeks of pregnancy, ultrasound is performed to exclude congenital malformations and ultrasound markers of chromosomal mutations in the fetus. Considering the high risk of developing fetoplacental insufficiency, it is necessary to perform a Doppler study of fetal blood flow [8, 9]. Carrying out an EEG and determining the concentration of PEP in the blood are advisory in nature, since they are not regulated by this order, but if attacks are observed during pregnancy, then these studies are performed every time the patient visits a neurologist.

According to the European Registry of Epilepsy and Pregnancy [35], GTCS are registered in 15.2% of pregnant women. Deterioration of control over ES during the first and second trimesters of pregnancy is observed in 15.8% of cases; the risk of ES during childbirth is approximately 2.5%, while the likelihood of its occurrence is higher in the presence of GTCS during pregnancy [33, 36-39] .

AEDs according to the classification of risk categories for the fetus (FDA) are divided into three categories: C - risk cannot be excluded, D - risk proven and X - contraindicated during pregnancy. Drugs, category C - representatives of the second generation of AEDs (lamotrigine, ethosuximide, levetiracetam, oxcarbazepine, lacosamide, zonisamide, perampanel, tiagabine) [30, 34, 40, 41]. They do not have a pronounced teratogenic effect, but can cause various defects in fetal development, intrauterine growth retardation, malformations of the cardiovascular system (ventricular septal defect, valvular anomalies), visceral anomalies (perampanel), delayed ossification (lamotrigine), etc. First generation drugs (valproic acid, carbamazepine, phenobarbital, clonazepam) can cause more severe birth defects and malformations in the form of clefts of the hard palate, craniofacial defects, skeletal anomalies, coagulation defects, neural tube development defects, spina bifida [38, 42-44] .

The risk of developing congenital defects and anomalies is 2-3 times higher in children born to mothers who were treated for epilepsy during pregnancy [3, 39, 40]. All AEDs cross the placenta and have some teratogenic potential, but drug concentrations vary at different stages of pregnancy as a result of binding to plasma proteins and metabolism. In this case, a decrease in the concentration of the drug is observed as the duration of pregnancy increases. By the time of birth, it drops to a minimum level and over the next 8 weeks returns to the initial level [34, 40, 45, 46].

Epilepsy is not a contraindication to vaginal delivery. Performing a cesarean section is possible only if status epilepticus occurs, an increase in epileptic seizures in the prenatal period and if there are negative dynamics in the condition of the fetus. However, at present, these contraindications are relative, and termination of pregnancy can only be carried out with the woman’s consent. Early delivery is carried out in case of serial epileptic seizures or status epilepticus [7-10, 39].

When choosing labor anesthesia, preference is given to epidural anesthesia, but if the circulation of cerebrospinal fluid is impaired with the involvement of the liquorocirculatory spaces, its use is contraindicated. It is possible to use general (central) anesthetics with low epileptogenic potential. The use of dissociative anesthetics - ketamine and its analogues, as well as halogen-containing inhalational anesthetics (halothane, sevoflurane, desflurane, etc.) is not recommended due to their proconvulsant effect and the high risk of failure of epilepsy remission in the early postpartum period [37, 38, 43 , 44].

In the early (7 days) and late (3 months) postpartum period, women are advised to regularly continue to take AEDs, as there is a risk of decompensation of epilepsy. One should be wary of PEP intoxication due to blood loss during childbirth and the postpartum decrease in the total body weight of the postpartum woman. If drowsiness, nystagmus and ataxia occur, the concentration of AEDs in the blood should be urgently checked and the patient should be advised to return to the daily dose of the drug used before pregnancy [21, 22, 45].

The decision to breastfeed is made on an individual basis. Taking AEDs is not an absolute contraindication to breastfeeding, but if a woman is taking drugs with a sedative effect (phenobarbital or benzodiazepine), then the child’s condition should be monitored to avoid excessive sedation. Feeding is carried out in a supine position to avoid a possible fall during a seizure [20, 21, 45, 46]. Organizing a sleep-wake schedule and avoiding shortening the duration of night sleep become important steps to prevent EC [26, 46, 47].

Thus, epilepsy may have a negative impact on pregnancy outcome, and pregnancy may worsen the disease; Pharmacotherapy can affect the health of the newborn. Women of reproductive age should be advised to plan a pregnancy only after careful consultation with an epileptologist, weighing the degree of risk of pregnancy.

Information about authors

Ziganshin A.M. — Ph.D., Associate Professor; e-mail; https://orcid.org/0000-0001-5474-1080;

Kulavsky V.A. - Doctor of Medical Sciences, Prof.; e-mail; https://orcid.org/0000-0001-5438-6633;

Vashkevich A.G. — email

*e-mail; https://orcid.org/0000-0001-5474-1080

Preeclampsia and eclampsia in patients with epilepsy

Eclampsia is considered a condition characterized by the development of one or more generalized seizures in a woman with preeclampsia. In half of the cases, eclampsia develops before childbirth; the frequency of its occurrence during childbirth and in the postpartum period is approximately the same.

Preeclampsia is characterized by arterial hypertension with proteinuria and edema in the second half of pregnancy. The diagnosis of severe preeclampsia is made when one of the following criteria is present:

increase in systolic blood pressure more than 160 mm Hg. Art. or diastolic blood pressure more than 110 mm Hg. Art., registered twice with an interval of more than 6 hours;

loss of protein in urine more than 5 g/day or a sharply positive result of a rapid urine test for protein;

oliguria (urine amount below 400 ml/day);

severe headache (due to cerebral edema) or blurred vision (due to retinal edema or spasm of the retinal arteries);

signs of pulmonary edema and cyanosis.

Severe preeclampsia is an indication for immediate delivery. Seizures in eclampsia should be regarded as provoked, occurring against the background of acute brain damage. Encephalopathy in eclampsia develops as a result of impaired autoregulation of cerebral blood flow and increased capillary permeability. This leads to cerebral edema, the development of multiple microhemorrhages and disseminated intravascular coagulation, which is the cause of attacks. The risk of eclampsia is not always proportional to the severity of arterial hypertension. In young primiparous women with initial arterial hypotension, eclampsia can develop with an average blood pressure of 120–130 mm Hg. Art. Therefore, effective antihypertensive therapy is required in all cases of preeclampsia, although this does not have a significant effect on the transition to eclampsia. Among antihypertensive drugs, vasodilators should not be prescribed, since they have the ability to enhance the increase in perfusion cerebral edema.

Another area of therapy is seizure control. In the past, benzodiazepines and phenytoin were used to relieve attacks. Currently, a solution of magnesium sulfate is considered the most effective remedy. As a prophylactic agent for severe preeclampsia in the antenatal period, magnesium sulfate can be administered intramuscularly, or intravenously in the presence of seizures. The drug is administered intravenously in a slow stream at a dose of 4 g (16 ml of a 25% solution), and then 1 g (4 ml of a 25% solution) every hour during the day. On the first day, additional administration of 2–4 g of magnesium sulfate may be necessary if attacks continue. Subsequently, they switch to intramuscular administration of the drug.

During therapy, monitor the level of urine output (more than 100 ml/h), the frequency of respiratory movements (more than 12 per minute) and the preservation of tendon reflexes. A change in these indicators indicates the toxic effect of magnesium sulfate. To adjust the dosage, intravenous bolus injection of 10 ml of a 10% calcium gluconate solution is used. Calcium channel blockers (nifedipine) should not be prescribed together with magnesium sulfate due to the common mechanisms of action of these drugs.

If therapy with magnesium sulfate is ineffective, additional administration of a diazepam solution of 10 mg 1–2 times/day is used. The lack of effect of such therapy indicates the need for intravenous barbituric anesthesia.

Medical Internet conferences

Introduction.

Epilepsy is a chronic brain disease characterized by the presence of an epileptogenic focus and spontaneously occurring convulsive or non-convulsive seizures. According to statistics, up to 3% of the population suffers from epilepsy; it is one of the most common neurological diseases.

Also, patients suffering from epilepsy often experience reproductive dysfunction. For example, men diagnosed with epilepsy often experience a decrease in the quality of erections and subfertility. There are various combinations of factors that together cause erectile dysfunction in epilepsy. Endocrine disorders can be caused by abnormal functioning of the hypothalamic-pituitary system during epileptic discharges of the brain, and the release of anticonvulsants and their metabolites into the seminal fluid can lead to asthenozoospermia.

Target.

Assessing the impact of epilepsy on male reproductive function.

Materials and methods.

A study was carried out on 30 male patients suffering from epilepsy, aged from 23 to 40 years. All patients selected for the study were divided into 2 groups. Group I consisted of 14 patients with a congenital anomaly of the central nervous system. Group II included 16 patients with post-traumatic epilepsy. Along with this, a separate age-matched control group of 15 somatically and neurologically healthy men was formed. Information about the erectile function of men was obtained by filling out the IIEF-5 (International Index of Erectile Function) questionnaire. A spermogram served as a surrogate criterion for the fertility of the men studied. During statistical processing, the Mann-Whitney test and the chi-square test were used.

Results.

In group I, a statistically significant difference was noted with the control group in two assessed parameters (erectile function and sperm quality); in it, asthenozoospermia was significantly more common (71.4% versus 20%, p<0.05) and erectile dysfunction (IIEF-5 median 13.5 versus 23.2, p<0.01). In group II, no statistically significant difference with the control group was observed.

Conclusion.

According to the results of the study, it was found that erectile dysfunction and fertility disorders are more common in people with epilepsy since childhood or adolescence, which may be due to profound disturbances in neuroendocrine regulation under the influence of a long-existing epileptoid focus and prolonged exposure to antiepileptic drugs.