01.11.2017

Interesting

Bogacheva Sharofat Bairovna

The brain is a “mystical” organ that can fill us with incredible sensations, show us our own “movie”, dreams, accumulate experience and wisdom that allows us to think. This is an organ that controls and regulates the functioning of the entire organism as a whole and each organ and system separately; providing the balance, protection, and compensatory reactions to disturbances necessary for our body. This small organ, weighing about 1400–1500 g (2% of body weight), has incredible abilities that have not yet been fully studied.

What does the brain need? Working without rest day and night, he is in dire need of oxygen (the brain consumes 20% of all oxygen entering the body) and nutrients, without which he cannot live even for a few minutes. It is a known fact that oxygen reserves are not created in the brain, and there are no substances that can nourish it under anaerobic (in the absence of oxygen) conditions. That is, the nerve cells of the brain constantly need oxygen, glucose and “cleaning” (cleansing of cell waste products).

Etiology of transient cerebrovascular accidents

Transient disturbance of cerebral blood flow (TCI) is an acute disturbance of the blood circulation of the brain, which is accompanied by the appearance of focal, cerebral or mixed symptoms.

PNMK occurs in 30% of the population.

The main causative factors in the development of PNMK are: hypertension, symptomatic hypertension, atherosclerosis, vasculitis with autoimmune connective tissue lesions, heart defects, acute cardiac disorders (myocardial infarction, acute coronary syndrome, exertional angina), osteochondrosis of the cervical spine, vertebral artery syndrome .

The following forms of PNMK are distinguished: transient ischemic attacks (TIA) and hypertensive crises. PNMK of the TIA type is a short-term disturbance of blood flow and is not accompanied by pronounced destructive changes in brain tissue, but sometimes TIA can lead to the formation of cysts of small diameter.

Typically, TIA-type PNMK is reversible and this is due to the large compensatory capabilities of the brain, but it tends to form “silent” zones.

PNMK of the TIA type may also include diffuse atrophic changes in brain tissue, which can serve as a trigger in the development of ischemic stroke.

One of the causes of PNMC may be congenital vascular anomalies, for example, coarctation of the aorta, hypo- or aplasia of the arteries, pathological tortuosity of the choroid plexuses.

Severe spasm of the neck muscles, pathological compression from the outside by a growing tumor, enlarged lymph nodes can play an important role in the formation of PNMK.

Modern ideas about chronic cerebrovascular insufficiency

In turn, the prevalence of dementia is 5–10% among people over 60 years of age [3]. Based on the data presented, we can conclude that 0.5–2.5% of older people suffer from vascular dementia. The number of people with vascular cognitive disorders that do not reach the severity of dementia is presumably 2–3 times greater than the number of people suffering from vascular dementia [3, 4]. Thus, the prevalence of CNMK can reach up to 10% of people over 60 years of age.

In domestic neurological practice, several synonymous diagnostic formulations are used to designate CNM:

- dyscirculatory encephalopathy (DEP);

- chronic cerebral ischemia;

- hypertensive encephalopathy;

- chronic cerebrovascular insufficiency;

- chronic cerebrovascular insufficiency;

- chronic cerebrovascular disease;

- ischemic brain disease.

All of the above diagnostic formulations can be considered as synonyms that denote a clinical syndrome that develops with chronic progressive non-stroke brain damage. Such a significant variety of diagnostic formulations reflects the history of the study of CNM, the evolution of views on this problem and the current lack of a unified view on the pathogenetic mechanisms and clinic of CNM.

The term “dyscirculatory encephalopathy” was proposed in 1958 by outstanding Russian neurologists Professors G.E. Maksudov and V.M. Kogan [5]. This term has been proposed to understand chronic progressive diffuse brain damage as a result of chronic ischemia and hypoxia, which is manifested by progressive cognitive and other neurological disorders. In 1985, this term was included in the domestic classification of vascular diseases of the brain, adopted at the plenum of the All-Union Society of Neurologists (Fig. 1) [6].

Development of neuroimaging methods at the end of the 20th – beginning of the 21st centuries. forced us to subject a certain revision to the idea of the pathogenetic mechanisms of development of the clinical syndrome of DEP. It has been shown that, along with chronic ischemia and hypoxia, which leads to the development of diffuse changes in the white matter (leukoaraiosis (LA)), a significant contribution to the development of DEP is also made by repeated acute cerebrovascular accidents without clinical stroke - the so-called “silent” infarctions. They develop asymptomatically or with minimal, erased or atypical symptoms, which do not allow recognition of a stroke. However, subsequent accumulation of brain damage as a result of repeated “silent” infarctions contributes to the further progression of DEP [7, 8].

In connection with new ideas about the mechanisms of formation of DEP in 2001, Academician of the Russian Academy of Sciences, Professor N.N. Yakhno proposed a new edition of the definition of DEP: “dyscirculatory encephalopathy is a syndrome of various etiologies, manifested by progressive neurological, neuropsychological and mental disorders, which develops as a result of repeated acute cerebrovascular accidents and/or chronic cerebral circulatory failure” [9]. The above definition clearly demonstrates the preference of the term “dyscirculatory encephalopathy (various pathogenetic mechanisms of vascular damage to the brain are allowed) over the term “chronic cerebral ischemia” (meaning the presence of one mechanism of brain damage).

Etiology and pathogenesis of DEP

DEP is not an independent disease, but a complication of various cardiovascular diseases. The list of causes of CNM repeats the list of causes of strokes (Table 1). In practice, most often CNMC develops as a result of long-term uncontrolled arterial hypertension, atherosclerosis of the cerebral arteries and atrial fibrillation with repeated microthromboembolism in the brain.

The common etiological factors determine the high comorbidity of DEP and strokes. Typically, patients with DEP have a history of stroke, and patients who have had a stroke also have DEP. In the presence of a history of stroke, the diagnosis of DEP is legitimate if the stroke cannot explain all of the patient’s symptoms and if another concomitant disease (for example, neurodegenerative) is excluded.

There are 3 main pathogenetic mechanisms for the formation of chronic progressive non-stroke vascular lesions of the brain in DEP [8–11]:

- repeated acute cerebrovascular accidents without clinical stroke (“silent” heart attacks or “silent” hemorrhages);

- LA;

- secondary cerebral atrophy.

As a rule, “silent” infarcts have a small volume, i.e., they belong to the category of lacunar infarcts (less than 10–15 mm in diameter). A single lacunar infarction may remain asymptomatic. However, with repeated lacunar infarctions (which is often observed in the absence of adequate treatment of arterial hypertension), the accumulation of brain damage leads to the formation of neurological symptoms. Moreover, this symptomatology will develop gradually – like a chronic vascular lesion of the brain [7, 8].

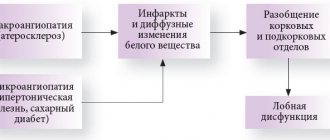

The nature of neurological symptoms in repeated lacunar infarctions is determined by their location. Due to the anatomical and physiological characteristics of the cerebral vascular system, lacunar infarctions are most often found in the subcortical basal ganglia, internal capsule, pons and cerebellum [7, 8].

Damage to the subcortical basal ganglia (striatum, thalamus) as a result of lacunar infarctions leads to secondary dysfunction of the frontal lobes of the brain. This is explained by the presence of a close functional connection between the frontal cortex and subcortical formations. Therefore, disruption of the interaction between these areas leads to secondary dysfunction of the frontal cortex. Clinical analysis of neurological and neuropsychological symptoms, which are observed in the initial stages of CNM, indisputably indicates its connection with dysfunction of the frontal lobes of the brain [8–11].

LA is commonly understood as changes in the density and anatomical structure of the white matter of the brain, which are very common in old age and are often associated with vascular diseases. In this case, blanching of certain areas of the white matter of the brain is determined macroscopically, and demyelination, gliosis and expansion of perivascular spaces (criblures) are determined microscopically [8, 10–13].

The pathogenetic mechanisms of the development of LA remain incompletely understood. It is assumed that endothelial dysfunction plays an important role in this, which leads to increased permeability of the microvascular wall. As a result, the blood-brain barrier is disrupted, blood plasma leaks into the brain parenchyma, and chronic edema of certain parts of the white matter (primarily periventricular) is formed, which over time can lead to secondary morphological changes. It is also believed that repeated episodes of transient local cerebral ischemia without the formation of cerebral infarction (the so-called “incomplete” infarctions) are of great importance for the occurrence of PA [8, 10–13].

LA leads to disruption of communication between various cortical, as well as between cortical and subcortical structures (disconnection phenomenon). As a result of disconnection, the frontal lobes of the brain suffer the most, which is associated with their physiological role. The fact is that the function of the anterior parts of the brain is to control cognitive activity and behavior. In the absence of communication with other parts of the brain, this function cannot be performed [10, 11].

Cerebral atrophy is a natural result of damage to white matter in chronic insufficiency of blood supply to the brain. It develops according to the mechanism of the so-called “Walerian degeneration”: separation of the frontal lobes from the rest of the brain leads to a decrease in the activity of neurons in the anterior parts of the brain. According to general physiological laws, in functionally inactive (and therefore “unnecessary” neurons) the process of genetically programmed death (apoptosis) is triggered, which leads to cerebral cortical atrophy. In this case, the maximum severity of the atrophic process is observed in the anterior parts of the brain. With neuroimaging, this is manifested by a disproportionate expansion of the subarachnoid spaces in this area [14, 15].

Clinical picture of DEP

The clinical picture of DEP is highly variable. However, in the vast majority of cases, the clinical picture is dominated by neurological, emotional and cognitive dysfunctions of the frontal lobes of the brain, which reflects the pathogenetic basis and localization of the pathological process in DEP. The most commonly observed are various combinations of cognitive impairment, depression and/or apathy, and disorders of postural stability, balance and gait [10, 11, 16, 17].

Traditionally, there are 3 stages of DEP [9]:

Stage I. It is characterized by so-called subjective neurological symptoms: headache, dizziness, noise in the ears or head, increased fatigue, sleep disturbance, forgetfulness. Objectively, “scattered” neurological symptoms are detected in the form of increased and/or asymmetry of tendon reflexes, mild incoordination, nystagmus, intention tremor, etc. It was previously assumed that the clinical symptoms at this stage are based on dysfunction of neurons as a result of chronic ischemia and hypoxia without formation structural defect. However, the development of neuroimaging methods has convincingly shown that in reality, structural changes precede dysfunction: for a sufficiently long time, vascular lesions of the brain can remain asymptomatic. Currently, there is a widespread idea that the subjective neurological symptoms of stage I DEP are based on emotional disorders associated with frontal dysfunction: the so-called vascular depression or emotional lability [17–20].

At stage II of DEP, subjective neurological symptoms lose their relevance, criticism decreases, and at the same time, more distinct objective neurological symptoms are formed. One or more of the following neurological syndromes may develop [9]:

- moderate cognitive impairment (Table 2);

- pseudobulbar;

- gait and balance disorders (frontal dysbasia);

- amyostatic;

- pyramidal

At stage III of DEP, a combination of several of the above neurological syndromes is observed, cognitive impairment reaches the severity of dementia, and pelvic disorders are added [2, 9].

Diagnosis and differential diagnosis of DEP

To diagnose DEP syndrome, the presence of cognitive impairment and other characteristic neurological symptoms, underlying vascular disease, and evidence of a cause-and-effect relationship between the vascular disease and CNS damage are required (Table 3).

One of the significant evidence of the vascular nature of brain damage is the characteristic features of cognitive status. With DEP, at least in its initial stages, memory impairments are absent or present to a small extent. Violations of frontal control functions come to the fore in the structure of cognitive disorders in the form of decreased mental activity, impaired planning, cognitive inertia and lack of control [16, 22, 23]. To identify these disorders, specific “frontal” neuropsychological tests should be used. In particular, “frontal” tests are included in the Montreal Cognitive Impairment Scale (Moka Test). The international scientific community currently recommends their use for screening for non-dementia vascular cognitive disorders [24].

A challenging but pressing clinical challenge is the differential diagnosis between vascular and primary degenerative cognitive disorders, since DEP and neurodegenerative processes are the most common causes of cognitive impairment in older people. The differential diagnosis is based on an analysis of neuropsychological characteristics and neurological symptoms. As mentioned above, in DEP, disturbances of “frontal” executive functions predominate, while in the neurodegenerative process, memory impairments predominate. The neurological status of DEP reveals pseudobulbar, amyostatic syndromes, balance and gait disorders. In primary degenerative cognitive disorders, focal neurological symptoms are absent until the stage of severe dementia [2, 9, 17, 22, 23].

For the differential diagnosis of DEP and the neurodegenerative process, as well as the identification of combined forms, the modified Khachinsky scale is used (Table 4) [25].

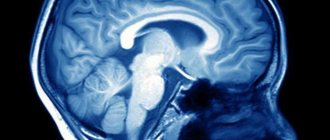

Reliable verification of the diagnosis of DEP is neuroimaging - computed tomography, x-ray or, preferably, magnetic resonance imaging. This research method makes it possible to visualize the consequences of acute disorders of the brain and PA [10, 11]. The presence of these changes is indisputable evidence of vascular damage to the brain. However, even in the presence of proven vascular cerebral damage, clinical symptoms can be caused by various reasons. Thus, at least 15% of dementia in old age belongs to the so-called “mixed” dementia, when cerebrovascular insufficiency is combined with Alzheimer’s disease. Such a frequent combination of vascular and degenerative brain damage is explained by common risk factors and pathogenetic mechanisms [26].

Treatment of DEP

DEP is not an independent nosological form. This is a polyetiological syndrome that can complicate the course of various cardiovascular diseases, for example, arterial hypertension, cerebral atherosclerosis, etc. Treatment of DEP should first of all be aimed at the underlying disease. Only optimal control of all existing risk factors for cerebrovascular accidents makes it possible to stop or slow down the progression of cerebrovascular insufficiency. Treatment of the underlying vascular disease thus constitutes etiotropic therapy for DEP. It usually repeats measures for secondary prevention of stroke and includes antihypertensive, antiplatelet, or anticoagulant, and lipid-lowering therapy, and vascular surgery methods.

Pathogenetic therapy for DEP should be aimed at optimizing cerebral blood flow and creating neurometabolic protection of the brain from ischemia and hypoxia.

In everyday practice, vasoactive drugs that affect cerebral microcirculation are most often used. Such drugs include:

- phosphodiesterase inhibitors: pentoxifylline (Vazonit®), vinpocetine, aminophylline, standard ginkgo biloba leaf extract, etc. The phosphodiesterase enzyme is involved in the metabolism of cyclic adenosine monophosphate. An increase in its content in the smooth muscle cells of the vascular wall as a result of a decrease in phosphodiesterase activity leads to their relaxation and an increase in the lumen of the vessels;

- calcium channel blockers - cinnarizine, nimodipine, diltiazem also have a vasodilating effect, which is based on a decrease in the content of intracellular calcium in the smooth muscle cells of the vascular wall;

- α2-adrenergic receptor blockers: nicergoline, piribedil, α-dihydroergocryptine. These drugs eliminate the vasoconstrictor effect of the mediators of the sympathetic nervous system - adrenaline and norepinephrine, and also (due to their effect on cerebral presynaptic receptors) increase the activity of noradrenergic mediation in the brain.

An effective vasoactive drug that has proven itself in many years of clinical practice is pentoxifylline (Vazonit®, Austria). This drug is a derivative of methylxanthine, which has the ability to effectively inhibit type 4 phosphodiesterases in smooth muscle cells of the vascular wall and blood cells. The use of Vasonite leads to the expansion of small-caliber cerebral vessels. At the same time, according to experimental data, the drug has the greatest effect on the affected vessels in the ischemic parts of the brain. Therefore, the appointment of Vazonit does not cause the effect of “robbing”. In addition, inhibition of phosphodiesterase in blood cells reduces the aggregation activity of platelets and erythrocytes, increases the deformability of platelets and erythrocytes and reduces blood viscosity [27–30].

The dosage form of Vazonit is long-acting tablets, which allows you to take them 2 times a day - morning and evening. In this case, there are no night breaks in treatment, i.e., a full day is “overlapping” with a 2-time dose.

Pentoxifylline can be prescribed both orally and intravenously with a fairly wide range of doses. However, it is recommended to prescribe pentoxifylline in tablets of 600 mg (extended form) 2 times a day with food.

The effect of pentoxifylline can occur between the 2nd and 4th weeks, but treatment should continue for at least 8 weeks. [31].

The high effectiveness of pentoxifylline has been demonstrated both in numerous clinical studies and in many years of daily clinical practice. Thus, in the study of A.N. Boyko et al. Pentoxifylline was prescribed to 55 patients with consequences of non-severe stroke. With this therapy, a significant improvement in memory, attention and other cognitive functions was noted [27].

In the 1980s–1990s. More than 20 randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled studies have been conducted in European countries. Their results convincingly showed that the use of pentoxifylline in patients with vascular dementia and less severe cognitive impairment is accompanied by a significant improvement in cognitive function, as well as regression of other neurological disorders. At the same time, therapy with pentoxifylline contributed to a clinically significant reduction in the severity of cognitive and other neurological disorders both in CNMC and in dementia that developed as a result of repeated acute cerebrovascular accidents [28–30].

Over a long period of practical use, pentoxifylline has shown a high safety profile and good tolerability, including in elderly patients. The drug does not have a negative effect on vital functions and extremely rarely causes side effects [28–30].

In domestic practice, vasoactive drugs are usually prescribed in courses of 2–3 months. 1–2 rubles/year. However, recently the feasibility of longer-term vascular therapy has been discussed.

Neurometabolic therapy is also widely used for DEP. The goals of this type of treatment are to create neurometabolic protection of the brain from ischemia and hypoxia, as well as to stimulate reparative processes in the brain. Neurometabolic drugs include piracetam, ethylmethylhydroxypyridine succinate, choline alfoscerate, citicoline, etc.

Metabolic therapy is carried out in courses of 1–2 rubles/year. Pathogenetically justified and appropriate is the combined implementation of vasoactive and metabolic therapy.

In conclusion, it should be emphasized that influencing both the cause and the main symptoms of DEP will undoubtedly contribute to both slowing down the progression of DEP and regressing existing symptoms and, ultimately, improving the quality of life of patients and their relatives.

Pathogenesis of transient cerebrovascular accidents

If the patency of the vessels of the brain or vessels of the neck is impaired, for example, with atherosclerosis, vasculitis, thrombosis, blood circulation in the brain tissue may become difficult.

This leads to ischemia of brain tissue and activation of metabolism with the production of under-oxidized products that trigger the destruction of phospholipids in cell membranes.

The result of such exposure is the death of brain cells with the development of atrophic diffuse foci, which leads to dysfunction of the nervous system and is manifested by various symptoms.

Etiological factors

The cause of the development of insufficiency, which is especially common in elderly and senile patients, is small-focal or diffuse damage to brain tissue. It develops against the background of long-standing problems with cerebral circulation, since during ischemia the central nervous system does not receive enough oxygen and glucose.

The most common causes of chronic ischemia:

atherosclerotic changes (in particular, cholesterol plaques);- hypertonic disease;

- VSD (vegetative-vascular dystonia);

- chronic heart failure;

- arrhythmias (including paroxysmal);

- diabetes;

- systemic vasculitis;

- blood diseases (with an increase in its viscosity);

- vascular lesions due to chronic infections (tuberculosis, syphilis).

One of the etiological factors is considered to be anomalies in the development of the aortic arch and vessels of the neck and shoulder girdle. They may not make themselves felt until atherosclerosis and hypertension develop. Certain importance is attached to compression (squeezing) of blood vessels by bone structures (with spinal curvatures and osteochondrosis) or tumors.

Blood circulation may also be impaired due to deposits of a specific protein-polysaccharide complex, amyloid, on the vascular walls. Amyloidosis leads to dystrophic changes in blood vessels.

In older people, low blood pressure is often one of the risk factors for CNMC. It does not exclude arteriosclerosis, i.e. damage to the small arteries of the brain.

Clinic of transient cerebrovascular accidents

Transient disorders of cerebral circulation, the symptoms of which can be divided into focal, cerebral or mixed.

Focal symptoms: loss of sensitivity, hypoesthesia or hyperesthesia of the skin of the face, limbs or torso.

Impaired motor activity with the development of paresis of the central type, which involves the muscles of the hands and feet.

Muscle hypotonia and decreased muscle strength are characteristic of TIA-type PMI. These processes can lead to the development of partial epileptic seizures.

Pathological reflexes may appear.

Visual impairment of the optic-pyramidal syndrome type appears with the development of monocular blindness on the side of the vessel occlusion.

General cerebral symptoms: nausea, vomiting, hiccups. Tinnitus, dizziness, imbalance, horizontal nystagmus, abnormal head position, photopsia, visual field defects, these symptoms may indicate a cerebrovascular accident.

Disorders of the bulbar part of the brain may occur: dysphonia, dysphagia, dysarthria.

Sudden attacks of muscle hypotension and immobility may occur with preserved consciousness.

Hypertensive crises are the result of a sharp increase in blood pressure, and are accompanied by vegetative symptoms.

Diagnosis of transient cerebrovascular accidents

The diagnosis is made on the basis of the patient’s complaints, medical history and illness, the presence of concomitant pathologies, clinical examination, laboratory and functional research methods.

The diagnosis of PNMK is made when stenosis of intracranial arteries is excluded; for this purpose, ultrasound scanning of vessels, MR angiography, and contrast angiography are used.

A coagulogram is examined, and a CT and MRI of the brain is also performed.

The diagnosis of PNMK should exclude subarachnoid hemorrhage. The diagnosis of PNMK can be made as a concomitant pathology.

Treatment and prevention of transient cerebrovascular accidents

A transient disorder of cerebral circulation, treatment of which begins immediately after diagnosis.

Treatment of PNMK may include: drug therapy, the prescription of antiplatelet agents and anticoagulants after studying blood tests, plasmapheresis and, of course, physical therapy.

Physiotherapy as a treatment method for PMN has been used for many years and is highly effective.

Prevention comes down to quitting smoking, controlling blood pressure levels, correcting cholesterol and lipids in the blood, correcting blood glucose levels, and regular physical activity.

Symptoms

Symptoms of a cerebrovascular accident depend on the degree of damage to brain cells and the location of the area of the brain with impaired blood flow. In acute cerebrovascular accidents (hemorrhagic or ischemic stroke), movement disorders such as hemiplegia or hemiparesis develop.

In chronic cerebral circulatory disorders (also called discirculatory encephalopathy), symptoms develop gradually and are manifested by symptoms such as memory impairment, dizziness, headaches. At first, the patient does not have any impairment of intellectual abilities. But as there is a chronic lack of oxygen in the brain tissue, memory impairment begins to progress, personality disorders arise, and intelligence decreases significantly. Subsequently, the patient develops severe intellectual-mnestic and cognitive impairments and dementia develops; extrapyramidal disorders and cerebellar ataxia may also develop.