What are we doing wrong?

“In our country it is very difficult to get an honest answer,” says pediatric neurologist Anna OSTROVERKHOVA .

– Parents have a vague idea of what results they can expect from rehabilitation, they seize every opportunity to show their child to a “fashionable” doctor, get a second (read: “one hundred and fifth”) opinion, they look for those who promise to put the child on his feet, sometimes giving his last money to miracle procedures, magic medicines. Most parents believe that everything depends on perseverance and intensity of activities: if you actively engage, then the child can be “stretched” and he will walk. Behind the idea of restoring the child, the child himself is lost.

His entire childhood passes under the banner of rehabilitation; often there is no time left for childhood itself: endless painful and completely ineffective injections of nootropics and vitamins, courses of useless massage, exercise therapy through pain and tears. Very often, efforts are made in completely the wrong direction: complex and ineffective activities are carried out, and there is not enough strength, time, or understanding for simple but vital things, or understanding that these actions are the only thing the child really needs.

I see children with severe cerebral palsy (level V according to GMFCS), who are “treated” all their lives, receive courses of nootropics and drugs that improve cerebral circulation, and receive monthly massages. After 10-14 years, the parents of a child with tetraparesis, with severe contractures, with spastic dislocations/subluxations of the hips, severe pain, severe underweight have only one request: to remove tone and contractures, so that the child does not suffer from pain, so that there is a little easier to care for. They no longer expect him to speak or even learn to hold his head up.

Why are there no such “neglected” children (whom our parents desperately “treated” all their lives) in developed countries? What do they do differently from us?

Firstly, parents receive a detailed diagnosis that determines the level of the child’s motor and communication functions. Secondly, knowing the degree of impairment of motor functions on the GMFCS scale, doctors determine the rehabilitation prognosis and potential of the child and honestly inform his parents, without feeding the parents’ unrealistic dreams and hopes for the child’s full recovery. Thirdly, adequate rehabilitation goals are chosen.

In the example described above, the child will most likely be placed on a baclofen pump to reduce tone, surgical treatment is possible to reduce pain, parents will use special positioning techniques to prevent contractures, the child will receive adequate nutrition, and will undergo medical examinations, including x-rays of the hip joints. The family will be provided with psychological support, parents will be taught alternative ways of communicating with the child.

But this is another illustration of the fact that a bitter truth is better than a sweet lie. Yes, the child will also not have the ability to move independently and perform purposeful actions, but he will be of adequate weight, without contractures, dislocations and pain, most likely he will have the strength for non-verbal communication, and it will be much easier for parents to care for him in adolescence."

Treatment of cerebral palsy

The general objectives of surgical treatment of spastic cerebral paresis in children are as follows:

- 1) simplification of coordinated muscle activity (while maintaining their participation in the motor reaction) by interfering with the peripheral motor unit. This simplification is best achieved by moving the tendon of a contracted biarticular muscle, transforming it into a single-joint muscle with a single function.

- 2) reducing the flow of proprioceptive impulses from the contracted and tense spastic-paretic muscle to the segmental motor neurons, which is achieved by suturing the tendons of the displaced muscle without the same tension.

These general tasks make it possible to determine indications and contraindications for surgical treatment of cerebral paresis in children.

- Only spastic (pyramidal) or mixed spastic-hyperkinetic paresis are subject to surgical treatment. An exception is hyperkinetic paresis of the upper limb with a sharp constant clenching of the hand into a fist and damage to the skin of the palmar surface of the hand with nails or with severe pain in tense muscles. In such patients, moving the flexors of the fingers and wrist together with the pronator teres muscle on the forearm does not improve hand function, but weakens the force of clenching into a fist and eliminates muscle soreness.

- Surgical treatment is indicated for children from 6-8 years of age, when conservative measures do not have an effect or contractures quickly recur after elimination; children over 10 years of age whose increasing contractures impair the ability to move and self-care.

- The operation is indicated only on a primarily contracted spastic-paretic muscle, which remains taut and under anesthesia with muscle relaxation.

- Surgical intervention on the tendon-muscular system involves maintaining balance in antagonistic muscle groups and maintaining stability in the joints.

Incorrectly defined indications for surgical treatment of childhood cerebral paresis can lead to deterioration and often to loss of previously existing functions and capabilities. Therefore, when choosing a treatment method, it is also necessary to strictly take into account reasonable contraindications.

- Orthopedic surgical treatment is contraindicated in pure hyperkinetic and atactic forms of paresis.

- Intervention is contraindicated on non-contracted spastic-paretic and secondary contracted muscles.

- For children with severe and widespread plegia involving the muscles of the back and neck (resulting in children actively being unable to support the head and body), surgical treatment is contraindicated. Only with severe adductor and flexion contractures in the knee and hip joints can surgical treatment be undertaken to facilitate the care of such patients.

- Corrective osteotomies (and especially joint arthrodeses) in patients with cerebral palsy are contraindicated, as they lead to the formation of discordant deformities that preclude the formation of static flexion settings that ensure a stable walking position.

All surgical interventions in children with cerebral spastic paresis should be performed only under anesthesia with controlled breathing. This is dictated by the need to reliably provide oxygenation to the brain.

Muscle relaxation with this type of anesthesia causes relaxation, but maintains tension in the contracted muscles.

Elimination of contracture of the hip joint.

In the hip joint in children with cerebral spastic lower paraparesis, flexion-adduction and internal rotation contractures are formed, for the elimination of which separate interventions are used. Flexion contracture is most often formed due to contracture of the rectus femoris muscle. Therefore, when such a contracture is identified, cutting off the proximal tendon of the muscle from the inferior anterior iliac spine is indicated.

The surgical technique is as follows: with the patient in the supine position, an arcuate incision is made 8-10 cm 1.5 cm below the superior anterior iliac spine. The fascia is dissected and entered into the intermuscular space between the sartorius muscle and the tensor fasciae lata, filled with fatty tissue. The muscles are bluntly pulled apart and the rectus femoris tendon is exposed, which is cut off and sutured to the intermuscular fascia on the thigh with maximum flexion at the knee joint. The patient is placed on his stomach, and the thighs are suspended on cuffs in the position of maximum extension on the Balkan frame.

In children, but more often in adolescents, with dislocation and subluxation of the hip and the presence of pain in the joint, there are indications for intrapelvic resection of the obturator nerve, and with severe flexion-adductor contracture - for cutting off the tendon of the rectus femoris muscle, closed myotenotomy of the adductor muscles of the thigh. To eliminate adductor contracture of the hip, intervention on the adductor tendons is more indicated. Closed myotenotomy of the proximal tendons of these muscles is carried out in an insufficient dose and therefore leads to the formation of a small abduction contracture, which patients are quite happy with.

S. Polock (I958, 1963) proposed that in the presence of adduction contracture in the hip and flexion joints in the knee, caused by contracture of the semi-tendon, semi-membranosus and gracilis muscles, their distal tendons should be transplanted from the lower leg to the thigh.

The surgical technique is as follows: with the patient lying on his stomach, a skin incision of 12-15 cm is made on the inside of the popliteal fossa, slightly curved anteriorly, over the above-mentioned tense tendons. The distal tendons of the semimembranosus, semitendinosus and gracilis muscles are isolated and then cut off almost at the insertion point on the lower leg. In the interval between the flexors and extensors of the leg, the posterior surface of the femur is exposed above the medial condyle, where the periosteum is longitudinally dissected for 2-3 cm. Its edges are mobilized and stitched with four to five threads of silk. These threads are used to stitch the cut tendons on both sides, which are immersed under the periosteum, and the threads are tied. If there is a contracture of the adductor magnus muscle, the tendon is lengthened. The wound is drained and sutured tightly. The limb is fixed with a high plaster boot with full extension in the knee joint in abduction and external rotation of the hip.

In children with severe internal rotational and adductor contractures in the hip and flexion of the knee, there are indications for transplantation of the distal tendons of the semimembranosus, semitendinosus and gracilis muscles to the posterolateral surface of the lateral femoral condyle.

The surgical technique is as follows: with the patient lying on his stomach, a 15-18 cm incision is made through the middle of the popliteal fossa, and the incision on the thigh should be longer than on the lower leg. The internal skin flap is mobilized and retracted medially. The tendons of the semimembranosus, semitendinosus and gracilis muscles are exposed and cut off, if possible, at the site of their attachment to the bone. These muscles are mobilized along the tendon upward, cutting the peritenonium so that subsequent movement does not create torsion and pinching. The external skin flap is then mobilized and inserted bluntly between the vastus lateralis and biceps femoris muscles. The periosteum of the femur in the supracondylar region is incised longitudinally for 3 cm and separated. On each side, the periosteum is sutured with four to five strong silk threads. The tendons of the cut off muscles are moved diagonally outward, where they are sutured with some tension to the periosteum, preventing them from bending and twisting. The wound is drained and sutured tightly. The limb is fixed in a high plaster boot with the knee joint extended. Provide external rotation.

Elimination of flexion contracture of the knee joint.

With the two operation options described above, flexion contracture in the knee joint is also eliminated. However, with more severe and widespread paresis, flexion contracture in the knee joint may be caused by contraction of all flexors of the leg. In these cases, especially if there is weakness of the gastrocnemius muscle (after previously lengthening the calcaneal tendon), transplantation of the proximal tendons of the biceps femoris, semimembranosus and semitendinosus muscles from the ischial tuberosity to the thigh is indicated. However, this operation can only be performed if the function of the gluteal muscles is satisfactory.

The surgical technique is as follows: with the patient lying on his stomach, an arcuate incision of 10 cm is made along the gluteal-femoral fold above the ischial tuberosity. A longitudinal incision in patients with a predominantly sedentary lifestyle is irrational due to constant trauma and maceration of the postoperative scar. The gluteus maximus muscle is retracted upward and the ischial tuberosity with the tibial flexor tendons attached to it is exposed. Their common tendon sheath is dissected along, inside which the tendons of the semimembranosus, semitendinosus and biceps femoris muscles are isolated and cut off. Cutting off the tendon inside their vagina prevents damage to the sciatic nerve located on the outside and cutting of the adductor muscles on the inside. When the knee joint is extended, the severed tendons are displaced.

Elimination of flexion contracture of the ankle joint and foot deformity.

If the equine foot is formed due to contracture of the gastrocnemius muscle, then when the knee joint is flexed, the equinus decreases. In this case, transplantation of the heads of the gastrocnemius muscle from the thigh to the lower leg is indicated.

The surgical technique is as follows: with the patient lying on his stomach, a median incision is made in the popliteal fossa measuring 15-18 cm, mobilizing the edges of the wound from the inside and outside, exposing both heads of the gastrocnemius muscle. When cutting off the medial head, an elevator is placed under it from the inside out. Its obliquely running tendon is cut off above the elevator, which may damage the capsule of the knee joint, which must be sutured. The lateral head is isolated and the elevator is placed under it from the outside inwards. The common peroneal nerve is carefully retracted and maintained under visual control while the lateral head tendon is cut. After cutting off both heads and redressing the equinus of the foot, the heads of the gastrocnemius muscle are shifted to the lower leg, where they are sutured to the intermuscular fascia. The wound is drained and sutured tightly. The limb is fixed with a high plaster boot. The plaster on the back of the foot and ankle is cut out.

From the next day, wooden wedges are placed under the plantar surface of the foot to eliminate residual equinus. At the same time, active extension of the foot and fingers is trained. A slight equinus of the foot can be eliminated by dosed lengthening of the heel tendon.

In children after 12 years of age and adolescents, a bone equinopolovarus deformity of the foot develops, which can only be eliminated by triple arthrodesis, sometimes with an additional slight lengthening of the calcaneal tendon. When trying to use a distraction device to eliminate foot deformity or to eliminate residual deformity after the Silverschold operation and triple arthrodesis of the foot, we detected an increase in tonic muscle tension with a pronounced pain reaction. At the same time, Kh. A. Umkhanov (1985) widely used a distraction device to eliminate foot deformities in children with cerebral paresis with positive results. Thus, experience shows that relatively minor contractures of the joints (knee, ankle) can be eliminated by lengthening the tendons of the contracted muscles. With severe contractures of joints and muscles, movement of the attachment points of the proximal tendons of the contracted muscles is indicated, turning them into single-joint ones. Under these conditions, the function of the muscles is not weakened, but, on the contrary, the strength of their voluntary contractions gradually increases. The most important advantage of this intervention is the provision of conditions for training isolated muscle contractions and voluntary movements in the joints.

Elimination of contractures of the joints of the upper limb.

On the upper extremities with hemi- and tetraparesis, less often monoparesis, a subcortical or mixed cortical-subcortical type of paresis is observed. Therefore, surgical treatment of contractures and deformities on the upper extremities is resorted to much less frequently than on the lower extremities. Indications for them are contracture of joints and muscles, as well as severe painful tonic muscle tension. In the presence of pronator-flexion contracture in the elbow, wrist joints and finger joints, transplantation of the proximal flexor tendons of the wrist and fingers together with the pronator teres tendon from the medial epicondyle of the humerus to the forearm is indicated.

The surgical technique is as follows: an arcuate incision (10-15 cm) is made along the palmar surface of the elbow joint, encircling the medial epicondyle of the humerus. The condyle with the muscles attached to it is exposed, while the ulnar nerve is isolated and retracted from their inner side. The vessels are located deeper. The elevator is brought under the selected muscles from the inside out with the elbow joint bent. The muscle tendons are dissected from the epicondyle while maintaining visual control of the ulnar nerve. Extension is performed in the elbow and wrist joints, as well as in the fingers and supination of the forearm and hand. The severed tendons are moved to the forearm, where they are sutured to the intermuscular fascia. The wound is drained and sutured tightly. The limb is fixed with a plaster splint in the position of supination and extension at the elbow and wrist joints, and the fingers of the hand are fixed on a cotton-gauze roller in the most extended position. This fixation is maintained for up to 3-4 weeks. Passive movements in the fingers begin in the first days after surgery, and then active ones are added.

Principles of rehabilitation from the perspective of evidence-based medicine

Photo: Anna Galperina

Ideas about the rehabilitation of children with cerebral palsy in the post-Soviet space and in developed countries differ.

“We generally believe,” shares Anna Ostroverkhova, “that the treatment of cerebral palsy consists of eliminating the damage that led to the disease. If the cause of cerebral palsy lies in damage to brain tissue, then it is imperative to “help” the brain, trying to “patch” the lesion, prescribing medications containing extracts of the brains of pigs and cows, be sure to “improve” blood circulation and flavor the brain cells with vitamins. Well, physical methods of rehabilitation consist only of improving/developing impaired motor function, and include the appointment of massage to relieve muscle tone, passive gymnastics, and older children do exercise therapy with an instructor.

Rehabilitation of children under one year old looks something like this: first, the massage therapist actively massages tense muscles (as a rule, this brings pain and discomfort to the child, which makes him scream and strain even more), and then does gymnastics with the child, passively bending/extending his limbs, doing exercises in which the child has a “led” role, i.e., the movements that the child makes are imposed on adults, and do not come from the child.

It turns out that the child becomes an object on which various actions are performed.

At the same time, an insane amount of parental effort, effort, emotional and material costs are spent on these actions. But if we compare the condition after rehabilitation of our children with cerebral palsy and children with the same initial data in Europe, America or Australia, then, frankly, a suspicion creeps in that we are doing something wrong. Our model turns out to be less efficient.

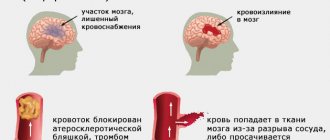

The modern rehabilitation model is based on different principles.

Firstly, we accept the fact that the area of the brain responsible for certain movements is damaged and, most likely, there is nothing in its place (a cyst with cerebrospinal fluid, for example), we do not try to “resurrect” these cells by introducing brain cells animals to an anatomical zone located at the completely opposite end of the body, improve blood circulation in those areas that physically do not exist. Also, we accept the fact that the cells that remain alive are absolutely functional and there is no need to improve anything in them either, because they were not damaged and remained normal. And these are not just philosophical arguments and conclusions. These are the results of studies that have not proven the effectiveness (and also safety) of nootropics and others like them.

No one in developed countries uses nootropics to treat anything.

Secondly, we recognize the fact that man is a rather lazy creature and will not try to do something for which he is not motivated. You can passively perform some kind of manipulation with a child for as long as you like, but if he is not motivated to perform the movement, or it is performed with great protest on the part of the child, after completing the rehabilitation course this skill is unlikely to be consolidated. Therefore, we definitely motivate the child to perform the movement (for example, the massage therapist not only skillfully turns the child from his back to his stomach, controlling the child’s legs, but a bright toy is placed next to the child, which he tries to reach, i.e., motivation is created, and already during the process, the adult can show the child how to perform the movement correctly).

In other words, the child must understand what he is doing and why. And for the purposes of the rehabilitation course, it will not be “decrease in tone in the upper extremities and improve fine motor skills” that will be prescribed, but a specific action that the child must learn to perform. For example, “learn to bring a spoon to your mouth, eat 10 spoons of porridge on your own.” To do this, undoubtedly, you will need to work on your tone and motor skills. But these will all be auxiliary things for a clear purpose and with good motivation.

Thirdly, the rehabilitation program is written individually for a specific child and cannot be the same for children even of the same GMFCS level.

We recognize the fact that no two children with cerebral palsy are alike.

Even if the lesion is absolutely the same and the possibilities of movement are also absolutely the same, most likely these will be children with different temperaments and different living conditions. One will live in an apartment building with a ramp, and his priority will be to keep his balance while reaching for the elevator button, or pick up the intercom and open the door, and the other will live in a private house, where it will be important to learn to keep his balance while walking through his mother’s garden and climb up the stairs to the second floor of the house, for example.

Fourthly, you need to work with your child every day. Classes with specialists are very important, but will be ineffective if they are not reinforced every day. Rehabilitation is primarily the work of parents; the task of specialists is to help parents create a program and train parents to perform tasks that they can perform in everyday life without being specialists.”

Stages of the disease

Depending on the age of the child and the symptoms of cerebral palsy that arise in him, it is customary to distinguish the following stages of development of this pathology¹:

- Early. Includes the period from birth to 4-5 months. Manifested by stiffness or lethargy, periodic shudders, convulsive seizures, inhibition of innate reflexes. These phenomena are often combined with severe breathing disorders, heartbeat, and increased intracranial pressure.

- Initial residual. Covers ages from 6 months to 3 years. At this stage, delays in mental and motor development begin to appear, which is why the skills of sitting, crawling, walking and speaking are formed late.

- Late residual. Occurs after 3 years. With it, the signs of the previously mentioned forms of cerebral palsy are finally formed, as well as persistent changes - muscle contractures and deformities. Speech and intellectual impairments become apparent.

Symptoms of cerebral palsy

Signs and symptoms of cerebral palsy vary greatly depending on the form of the disease and the characteristics of the central nervous system. The most typical manifestations³:

- Changes in muscle tone - increased tone (hypertonicity) or weakness of skeletal muscles (hypotonicity).

- Stiffness of movement - spasticity.

- Lack of balance and muscle coordination.

- Tremors or involuntary movements.

- Delay in the development of motor skills: sitting, crawling, walking.

- Pain when moving.

- Deformations of the limbs, their different lengths or overall size.

- Deformations of the chest and spinal column.

- Walking abnormalities, including: walking on your toes (video 2), crouching gait, excessively wide steps, asymmetry of steps.

- Excessive salivation, problems swallowing, weak sucking reflexes.

- Delays in speech development, incorrect pronunciation of words.

- Learning difficulties.

- Inability to make precise movements, such as fastening a button.

- Endocrine diseases: obesity, growth retardation, hypothyroidism.

With cerebral palsy, the pathological process may affect the entire body, or may be limited to one limb or side of the body. However, CNS lesions do not change over time, so symptoms usually do not worsen with age.

Video 2. Jumping gait, walking on the toes with cerebral palsy.

The earliest signs of cerebral palsy

The first signs of the disease in the early period (from 3 to 6 months) include:

- Lagging of the head from the body when lifting the baby from the crib.

- Movements of the arms and legs occur jerkily, with effort, or are almost completely absent.

- When held in arms, the baby arches his back and neck as if trying to push him away from himself.

- When rising from the crib, the legs become excessively tense and often cross each other with “scissors.”

- By the age of 3-4 months, a child’s reflexes do not disappear, preventing him from developing and walking.

At the age of 6-10 months, signs of cerebral palsy may include:

- No side turning when the child is lying on his back.

- Inability to join hands, visible difficulty in bringing fingers to mouth.

- Reaching for a toy with only one hand, while the other is clenched into a fist.

- When crawling - pushing the child away with only one arm and leg, dragging the limbs.

Some symptoms are not easy for parents to notice, but obvious markers should cause caution and be a reason to contact a neurologist. You should consult a doctor if the child cannot lift and does not hold his head by 3 months of life, cannot roll over by 6 months, does not crawl or sit at 10 months

Newborn reflexes that should disappear if the baby is healthy. Photo: Samuel Finlayson / Wikipedia (CC BY-SA 4.0)

A – Asymmetric cervical tonic reflex.

B – Grasping reflex. Photo: Wikipedia (Public Domain)

C – Support reflex. Photo: daihocyduoc/YouTube

D – Galant reflex. Photo: betapicts/YouTube

Brain abnormalities associated with cerebral palsy may also contribute to other neurological problems, including:

- Strabismus, visual and hearing impairment due to pathology of the cranial nerves.

- Limited intellectual capabilities.

- Convulsive seizures, epilepsy.

- Impaired tactile perception and pain.

- Urinary incontinence.

Not all children with cerebral palsy have intellectual disabilities. It is often difficult to assess the mental abilities of a child who has difficulty speaking and performing even simple actions. But this does not mean there is an intellectual deficit.

About life expectancy calculations

The life expectancy calculation is calculated from the average life expectancy in a given population of people with similar conditions. This estimate is based on historical and scientific data. This is not an exact lifespan. Any person can live much more, or less, than their expected life expectancy. It is necessary to understand this.

There are two main purposes for calculating the life expectancy of a person with cerebral palsy. First, answer the parent's question, “Is my child viable? And how long will he live? The parent wants to know the prospects for the child’s life and development, taking into account his state of health. How long will he live - days, weeks or years? Is he given a short life or a long, fulfilling life? Qualified doctors can usually answer these questions for parents.

Other purposes for calculating life expectancy are related to estimating future medical and rehabilitation costs. This may be related to obtaining compensation, or lifetime benefits due to medical negligence, or planning for expected expenses. A financial assessor analyzes many factors to obtain an estimate of life expectancy, which is then used to estimate the future financial costs associated with the child's treatment and rehabilitation. After all, this assessment is based on available scientific evidence and medical research.

Life expectancy is an indicator of mortality risk. This is the average number of years a person can live if mortality factors do not change. The mortality rate is decreasing due to the development of science and technology. Life expectancy is calculated based on several factors, but these factors can change over time, which may change the original calculation.

No person is guaranteed a standard path in life. Every person goes through major milestones in their life, but no one can say when, what and how will happen. Life expectancy cannot be predicted accurately, only estimated. These estimates are mainly used for rehabilitation planning and financial costs.

Why are children born with cerebral palsy?

By the diagnosis of “cerebral palsy,” experts mean a special abnormal condition in which a defect in the motor function of the brain occurs. Cerebral palsy in children can occur either in utero, during childbirth (intrapartum) or within a month after birth. Unfortunately, the diagnosis of cerebral palsy today is lifelong, and the patient’s main task is to control his movements and speech.

Modern researchers have not yet been able to establish the exact causes of cerebral palsy, but doctors have identified certain risk factors and, therefore, have learned to prevent them. According to research, about 80% of the problems leading to cerebral palsy are formed as a result of the influence on the fetus of various infections (neonatal sepsis, encephalitis, meningoencephalitis) and birth injuries (intracranial birth trauma, postpartum injuries of the central nervous system, hyperbilirubinemia of newborns), which cause abnormalities in brain development. According to Russian obstetrician-gynecologist, Professor Viktor Radzinsky, the main causes of cerebral palsy in children are birth trauma and oxygen deficiency during childbirth, which cause brain damage.