Dental implants solve a lot of problems in complex prosthetics, when there are difficulties in restoring acceptable function. When installing implants in the lower jaw, there is a significant risk of damage to any of the peripheral branches (inferior alveolar, mental, lingual nerve) of the mandibular part of the trigeminal nerve.

Although sensory impairment is a known and expected risk of some dental (medical and surgical) procedures, despite the highest quality care provided by the most qualified professionals, neurological complications are now the second most common cause of lawsuits against dentists in the United States.

Impaired sensitivity of oral structures is of great importance from a psychological and functional point of view. Anesthesia, soreness, or hypersensitivity may occur in the lips, cheeks, teeth, gums, or tongue. Drooling, choking on pieces of food or drinks, biting the lips or tongue, difficulty performing daily tasks such as shaving, applying makeup, talking, chewing, swallowing, kissing, smoking are a consequence of damage to the mandibular nerve and certainly cause extreme discomfort to the patient. especially if the patient was not warned about such complications in advance, and also if these problems are not completely resolved.

Nerve injuries do not always resolve on their own. However, in some patients they can be successfully treated using microsurgical techniques, provided they are performed promptly. In other patients, symptoms of nerve damage can be effectively managed with appropriate non-surgical therapy.

Causes of nerve damage

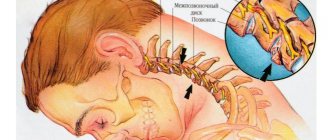

Injuries to the inferior alveolar, mental or lingual nerves result from compression, crushing, stretching, partial or complete rupture. In implantology practice, nerve rupture can occur when making an incision in the mucosa or when drilling into the bone to prepare an osteotomy hole for the purpose of inserting an implant. Nerve stretch occurs during prolonged retraction of the mucoperiosteal flap. Compression or crushing of the inferior alveolar nerve occurs as a result of the installation of a long implant. Injection of a local anesthetic may cause nerve damage through direct needle trauma or, more plausibly, through rupture of perineural or endonerval blood vessels with subsequent formation of scar tissue adhesions.

Primary trigeminal neuralgia, secondary trigeminal neuralgia

There are primary trigeminal neuralgia (idiopathic, essential, typical) and secondary trigeminal neuralgia (symptomatic trigeminal neuralgia).

With primary neuralgia (mainly of central origin), attacks occur for no reason or are provoked by any movements of the facial muscles.

Secondary neuralgia is usually a complication of the primary disease, has a predominantly peripheral genesis and is often caused by pathological processes in the dentofacial area. The pain is almost constant, periodically intensifying in the form of attacks lasting up to several hours.

Prevention methods

Careful planning and skilled execution of manipulations minimize the risk of nerve damage. Panoramic and periapical radiographs, supplemented by scanning (if indicated), make it possible to determine the height of the alveolar process above the nerve, the medial lateral and vertical localization of the canal of the mandibular nerve and the mental foramen. Careful soft tissue incisions help avoid direct contact with the mental and lingual nerves, and gentle retraction of the flap minimizes indirect stretch of the nerve. When preparing the osteotomy hole and installing the implant, it is necessary to avoid damage to the mandibular nerve canal.

In the absence of sufficient height of the alveolar process to install an implant without the risk of damage to the canal of the mandibular nerve, lateralization of the mandibular nerve is indicated. Implants can be placed during this procedure (Figure 1-3).

Figure 1. Nerve reduction. The inferior alveolar nerve prevents adequate implant placement.

Figure 2. Transoral reduction of the nerve and its lateral retraction.

Figure 3. The implants are installed in the desired position and at the required depth, and the nerve is repositioned.

Materials and methods

The studies were performed in 44 patients, aged from 28 to 71, who, according to surgical indications, required blocks of the 2nd and 3rd branches of the trigeminal nerve. The patients were divided into 6 groups, taking into account the regional blockade technique, neurostimulation modes, or the use of 3D CT guidance.

To perform nerve blocks, an isolated needle and a neurostimulator “Stimuplex HNS 12” (B/Braun) were used. Parameters of neurostimulation of the mandibular nerve (neurostimulation of the motor nerve): duration 0.1 ms, current strength 1-0.3 mA to achieve a motor response. Parameters of neurostimulation of the maxillary nerve (neurostimulation of the sensory nerve): pulse duration 0.3 ms, current strength 1-0.3 mA and frequency 1 Hz.

Group 1 (control) included 8 patients who underwent periorbital blockade (according to Voino-Yasenetsky) [7] in accordance with ESRA recommendations, with neurostimulation parameters for sensory nerves, and with the obligatory achievement of paresthesia. [3] Group 2 included 5 patients who underwent subzygomatic blockade of the maxillary nerve (according to S.N. Weisblat) [7];[9] with the same neurostimulation parameters for sensory nerves, but without achieving paresthesia [3].

Group 3 consisted of 12 patients who underwent subzygomatic blockade of the mandibular nerve (according to S.N. Weisblat) with neurostimulation parameters for motor nerves achieving a minimal muscle response when stimulated with a current intensity of 0.3 mA without achieving paresthesia.

Group 4 included 11 patients with blockade of the maxillary nerve, in whom neurostimulation parameters for the sensory nerve were used with the obligatory achievement of paresthesia.

Group 5 included 8 patients with blockade of the mandibular nerve according to S.N. Weisblatt, who used neurostimulation parameters for the sensory nerve with the obligatory achievement of paresthesia.

For the remaining 5 male patients (group 6), the needle was placed to the foramen ovale or pterygopalatine fossa using 3D computed tomography data (Siemens). To prevent nerve damage, neurostimulation was performed with parameters for the sensory nerve. The dose of Rg radiation did not exceed permissible values.

Regional blockades were performed with a mixture of local anesthetic solutions (0.25% bupivacaine with adrenaline (1:200000) and 1% lidocaine solution), prepared ex tempore. 3-5 ml of local anesthetic mixture was directly injected into each nerve. The dose of bupivacaine did not exceed 2 mg/kg, and lidocaine - 10 mg/kg. The effectiveness of RB was assessed using the “pin-prick” test.

Comparison of the obtained results was carried out using the nonparametric method 2 in the SPSS 20 program for Mac Os.

Classification of nerve injuries

Seddon described three types of nerve damage: neuropraxia, axonotmesis and neurotmesis. This classification is based on the relationship between the pathophysiology of nerve injury, the ability of the nerve to regenerate and clinical symptoms, which forms the basis for determining the prognosis of spontaneous recovery of sensitivity, indications and timing of surgery or other therapy.

Neuropraxia is a benign condition. There is temporary loss of sensation, but no anatomical damage to the nerve. Spontaneous recovery of sensitivity is possible within 4 weeks.

Axonotmesis is a more serious condition in which there is partial anatomical disruption of the integrity of the nerve and incomplete degeneration of the nerve distal to the injury. Initial symptoms of restoration of sensitivity do not appear until 6-8 weeks after the injury. Recovery may be incomplete (hypoesthesia) and is often accompanied by pain (dysesthesia).

Neurotmesis is a complete transection of a nerve or other complete disruption of its integrity with total degeneration of the portion of the nerve distal to the injury. There is little or no hope for spontaneous recovery. If the patient remains fully anesthetized for 3 months after injury, sensation is rarely recovered to a significant degree. Persistent and severe dysesthesia often develops. The progressive failure of the structures supporting the nerve and their replacement by scar tissue leads to the fact that, ultimately, 1 year after injury, even surgical intervention cannot restore nerve function in humans.

Clinical anatomy of the mandibular nerve

Knowledge of modern methods of conservative and surgical treatment of peripheral branches of n. trigeminus are relevant for doctors of various specialties. This knowledge makes it possible to carry out complex and multidisciplinary treatment of pathologies of the mandibular nerve with good long-term results.

Key words: mandibular nerve, trigeminal nerve, neuralgia, literature review.

Purpose: To conduct a theoretical analysis of modern methods of treating the mandibular nerve based on a review of modern literature.

Research methodology: Theoretical analysis. Review and analysis of literary sources on this issue for the period from 2000 to 2021.

The mandibular nerve (n. mandibularis) is the 3rd branch of the trigeminal nerve and is a mixed nerve. The nerve emerges from the foramen ovale and divides into motor and sensory branches.

Disorders in the trigeminal nerve system can be localized throughout all peripheral branches, as well as in the middle cranial fossa or in the central nervous system [1,2]:

- Peripheral branches may be damaged due to head trauma and be accompanied by loss of motor and/or sensory components. Herpes Zoster, a virus that causes herpes zoster and chickenpox, often causes neuralgia of the peripheral branches of the trigeminal nerve by invading the trigeminal ganglion.

- The middle cranial fossa can be damaged by a tumor - a meningioma, a schwannoma of the nerve itself, or a schwannoma of the auditory nerve at the junction of the cerebellum with the pons (“cerebellopontine angle syndrome”)

- In the central nervous system - demyelinating diseases (multiple sclerosis), vascular disorders and tumors:

a) Localization of the pathological process in the medulla oblongata will lead to loss of pain and temperature sensitivity

b) When the process is localized in the bridge, the path of discriminatory sensitivity, the innervation of the masticatory muscles of the corresponding side, is affected due to damage to the lower motor neurons

c) At a level above the brain stem, the transmission of all types of sensitivity on the opposite side of the head is disrupted, but motor function is preserved, because the motor nucleus is reflexively regulated by sensory impulses and receives bilateral innervation from the cerebral hemispheres.

Research results:

The most common cause of damage to the mandibular nerve is trauma to the maxillofacial area. According to the severity of the damage, according to the classification of traumatic damage to the peripheral branches of the trigeminal nerve according to I.O. Pokhodenko-Chudakova, E.A. Avdeeva and K.V. Vilkitskaya (2013), can be divided into:

1) Mild severity - short-term compression of the nerve, electroodontodiagnostics (EDD) less than 40

2) Moderate severity - hemorrhage, swelling around the nerve trunk, EDI - from 40 to 100.

3) Severe severity - prolonged compression, disruption of the integrity of the nerve, EDI - more than 100 [10,11].

The main goal of surgical treatment in this situation is to eliminate the primary factor of traumatic nerve damage—reposition of bone fragments and their fixation are performed [9]. Unfortunately, if not treated in a timely manner, the patient may develop a persistent pain syndrome and, against this background, secondary trigeminal neuralgia may occur. There are also primary or essential trigeminal neuralgia. Drug treatment of trigeminal neuralgia does not differ significantly in comparison with the treatment of other neuralgia of various localizations (vitamin therapy, sedatives), but it is worth noting that for this pathology the use of antiepileptic drugs (carbamazepine, baclofen, etc.) is very effective. [4,5,6,7]

For neuralgia of the mandibular nerve, surgical treatment methods are also used:

1) operations on peripheral branches (transection of the nerve trunk, alcoholization with endoneural administration of 80% ethyl alcohol), but, at the moment, these operations are used very limitedly, most often in elderly patients.

2) Surgery on the trigeminal ganglion or sensory root of the trigeminal nerve (percutaneous streotactic destruction of the trigeminal nerve, microvascular decompression) [3].

Traumatic nerve damage can also be caused by postoperative swelling of the nerve trunk. To avoid such complications, conservative treatment methods are used, which include drug therapy and the use of physiotherapeutic methods of treatment [7].

The mandibular nerve gives off the inferior alveolar nerve, which enters the mandibular canal of the mandible. This peripheral branch is very often injured due to iatrogenic effects due to careless work of the dentist. In this situation, to remove excess filling material or implant, which can injure and have a toxic effect on the nerve in the mandibular canal, LA operations are used. Grigoryantsev (2008), I. O. Pokhodenko-Chudakova and K. V. Vilkitskaya. [9]

Increasing attention is now being paid to microsurgical operations to restore the integrity of the nerve when it is completely or partially ruptured. For reconstruction, autogenous vein grafts, Gore-Tex tubular implants, and autogenous nerve tissue are used. Unfortunately, these methods only lead to positive results in 50% of patients [12,13,14,15].

In complex treatment, the method of transcutaneous electrical neurostimulation (DENS) is increasingly being used. This method is effective and has no side effects. The two most important disadvantages are the development of tolerance of somatosensory receptors to electric current, but this can be prevented by using different modes, and the presence of contraindications. The mechanism of action is the effect of high-amplitude weak voltage and, at the same time, low-frequency electric current, which causes a response in all types of nerve fibers. This technique is effective for peripheral paralysis and paresis of the masticatory muscles. Moreover, due to their atrophy on the affected side, facial asymmetry may occur over time [8,16,17,18].

It is important to note such pathologies with a polymorphic and little-studied etiology, such as glossodynia and glossoalgia. These diseases are characterized by the fact that at the histological level there is no process of inflammation and degenerative changes in the nervous tissue. Conservative treatment is mainly medicinal (vitamin therapy, sedatives) [19].

Conclusion:

The question of effective methods for treating the peripheral branches of the trigeminal nerve still remains open and is quite acute in view of the polymorphism and implicitness of the etiological factors of the pathology. Conservative treatment, in the vast majority of cases, only leads to relief of symptoms, and the effectiveness of surgical treatment is inversely proportional to its radicality.

Literature:

- Wilson - Pauwels L., translation, edited by A.A. Skoromets Cranial nerves. Function and dysfunction /L. Wilson - Pauwels. - M.: Publishing house: Panfilova; BINOMIAL. Knowledge Laboratory. 2013. - 272 p.: ill.

- Nikiforov A.S., “Clinical neurology”: textbook / A.S. Nikiforov - volume 1 - M.: Publisher: Medicine. 2002. - 600 p.

- Kulakov A.A. Surgical dentistry and maxillofacial surgery. National leadership: textbook for universities / A.A. Kulakov - M.: GEOTAR - Media, 2010. - 928 p.

- Gusev E.I. Neurology and neurosurgery: a textbook in 2 volumes / E.I. Gusev - M.: GEOTAR - Media, 2015. - 640 p.

- Gusev E.I. Neurology. National leadership: textbook for universities / E.I. Gusev - M.: GEOTAR –Media. 2021.- 1029 pp.

- Burykh M.P. Clinical anatomy of the cerebral part of the head / M.P. Burykh - M: - Caravel, Kharkov. 2002.- 240 p.

- Dudnik A.P. Surgical treatment of diseases and lesions of the peripheral system of the trigeminal nerve using microsurgical techniques: abstract of thesis. dis. — 14.00.21 / A.P. Angelica; — Central Scientific Research Institute of Dentistry. M., 2004. - 22 p.

- Pokhodenko-Chudakova I.O., Avdeeva E.A. Methodology of DiaDENS therapy in the treatment of patients with traumatic damage to the inferior alveolar nerve: instructions for use - M.: Minsk BSMU. 2010. - 8 p.

- Sergeev S.M. Stimulation of post-traumatic regeneration of the peripheral nerve in the diastasis zone: abstract. dis: 14.00.02, 03.00.25 / S. M. Sergeev; Saransk State honey. univ. Saransk, 2009.

- Pokhodenko-Chudakova I.O., Avdeeva E.A. Modern classification of traumatic injuries of the trigeminal nerve system / Pokhodenko-Chudakova I.O., Avdeeva E.A// News of surgery. 2013.- No. 6.

- Pokhodenko-Chudakova I.O., Avdeeva E.A. “Semiotics of cranial nerve injuries” educational and methodological manual / I.O. Pokhodenko-Chudakova, E.A Avdeeva. - M.: Vitebsk: VSMU, 2010. 245 p.

- Surgical treatment of trigeminal neuralgia with no neurovascular compression: A retrospective study and literature review 2021 Dec;58:42-48. doi: 10.1016/j.jocn.2018.10.066. Epub 2018 Oct 24.

- Bennetto L., NK Patel Trigeminal neuralgia and its management: British Medical journal/ Bennetto L., NK Patel, 2007 - 201.

- Bushell MC, AV Apkariam, Melzack's Representation of pain in the brain: Textbook of pain/ Bushell MC, AV Apkariam, Melzack's . 2006. - 124.

- Gary D. Klasser, Henry A. Gremillion and A. Dale Ehrlich, Neuropathic Orofacial Pain, Maxillofacial Surgery, 10.1016/B978-0-7020-6056-4.00101-5, (2017).Crossref

- Henry A. Gremillion, Gary D. Klasser and A. Dale Ehrlich, Orofacial Pain, Maxillofacial Surgery, 10.1016/B978-0-7020-6056-4.00102-7, (2017).

- N. Moreau, W. Dieb, A. Mauborgne, S. Bourgoin, L. Villanueva, M. Pohl and Y. Boucher, Hedgehog Pathway–Mediated Vascular Alterations Following Trigeminal Nerve Injury, Journal of Dental Research, 10.1177/0022034516679395, (2016 ).Crossref

- W. Dieb, N. Moreau, I. Chemla, V. Descroix and Y. Boucher, Neuropathic pain in the orofacial region: The role of pain history. A retrospective study, Journal of Dentistry, Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery, (2017). Crossref

- W. Ceusters, A. Michelotti, K. G. Raphael, J. Durham and R. Ohrbach, Perspectives on next steps in classification of oro-facial pain - part 1: role of ontology, Journal of Oral Rehabilitation, (2015). Wiley Online Library Crossref

Grade

Documentation of nerve damage is necessary to evaluate sensory deficits, decide whether and when to perform surgery or other treatment, and for legal reasons.

The medical history should include the reason for the operation, the date of injury, and symptoms of sensory changes (if any).

A study is being conducted to assess the severity of sensitivity disorders, for which neurosensory tests are used (response to irritating stimuli, static electricity, vitalometer, etc.). Re-evaluation is performed every 4 weeks until sensitivity is acceptable or other surgery is required.

Inflammation of trigeminal neuralgia: causes

What are the causes of inflammation, neuritis, trigeminal neuralgia? The causes of trigeminal neuralgia are various inflammatory (inflammation), traumatic (damage), toxic, infectious (infections, including herpes - postherpetic neuralgia), allergic, infectious-allergic, metabolic effects. Compression of nerves (pinching) in bone, musculoskeletal and osteoarticular canals, prolonged microtrauma, especially in combination with hypothermia, and foci of focal infection also play an important role.

Indications for microsurgery

The indications for surgery to correct nerve damage are based on the author's own experience, which includes the observation of more than 1000 patients and the performance of 375 microsurgical procedures to correct nerve damage, 21 of which resulted from dental implants between 1987 and 1996. year. The author's opinion regarding indications for surgical interventions is shared by many specialists in the field of microsurgery.

- Open (visible) nerve damage should be repaired as soon as possible. Such injuries usually occur during operations to install implants.

- Closed (non-visualized) damage must be repaired in the following order:

- Anesthesia lasting more than 3 months is reversed by suturing or nerve grafting.

- Dysesthesia that is unacceptable to the patient and lasts more than 4 months is eliminated with open exploration of the nerve through external decompression, internal neurolysis, excision of the neuroma, suturing and nerve transplantation.

- Severe hypoesthesia, unacceptable to the patient and lasting more than 4 months, can be eliminated by removing or partially unscrewing the implant, as well as by open exploration of the nerve and performing the manipulations described above.

- In general, patients who do not return to normal sensation within 4 weeks of surgery should be referred to a microsurgery specialist who can monitor the patient and modify the treatment plan as needed.

Other treatments

In general, implant removal does not eliminate nerve damage when treating nerve damage early. Nerve injury most often occurs during incision, flap retraction, or during osteotomy hole preparation. Nerve compression by an implant, unless severe, rarely results in permanent nerve injury.

Moderate dysesthesia or a syndrome of long-term (more than 1 year) painful nerve injury can sometimes be successfully treated with non-surgical treatments. Antineuralgic drugs (carbemazepine, phenytoin, clonazepam, bacolofen) or antidepressants (amitriptyline, notriptyline, imipramine), topical applications (capsaicin) or local anesthetic components (mixeltin) taken orally help patients with severe dysesthesia for whom surgery is not indicated or did not help. Other therapies (eg, acupuncture, transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation, psychological or psychiatric therapy, physical therapy) may play a role in treating the painful manifestations of nerve damage.

Summary

Despite the large number of different neuroimaging methods, there are certain difficulties when performing regional blocks of the 2nd and 3rd branches of the trigeminal nerve. The remaining problems are related to the complex anatomical structure of this area. The use of neurostimulation is not always effective and, as a rule, is associated with an incorrect interpretation of the development of the motor response to stimulation. Changing the tactics that involves searching for paresthesia improves the situation. The use of new neuroimaging methods (3D-CT) also makes it possible to reduce the number of failures during blockade of the branches of the trigeminal nerve to a minimum.

Key words: neuroimaging, neurostimulation, ultrasound guidance, combination of ultrasound guidance and neurostimulation, neurostimulation modes for sensory and motor nerves, local anesthetics, lidocaine, bupivacaine, periorbital block according to Voino-Yasenetsky, subzygomatic block according to Weisblatt, paresthesia, muscle response, regional blockades , trigeminal nerve, Gasserian ganglion block, anatomical landmarks, undeveloped block, lateralization of the block, neurostimulator, “pin-prick” test 3D computed tomography, anatomical deformations of the facial skull.

results

The prognosis for improvement or restoration of sensitivity after microsurgery depends on the age of the patient, the technical skills of the surgeon, and the length of the period between the fact of damage and surgical intervention aimed at eliminating its consequences.

From the author’s experience, in 80-90% of patients suffering from neurotmesis (usually expressed by anesthesia), operated on up to 6 months after the injury, it was possible to improve or restore sensitivity. Interventions performed more than 6 months after injury resulted in improvement in fewer patients. When operations were performed 1 year after the injury or later, the condition of less than 10% of patients improved. Patients who underwent surgery to correct dysesthesia after 9 months achieved improvement in 70% of cases, with worsening results as time to surgery increased.